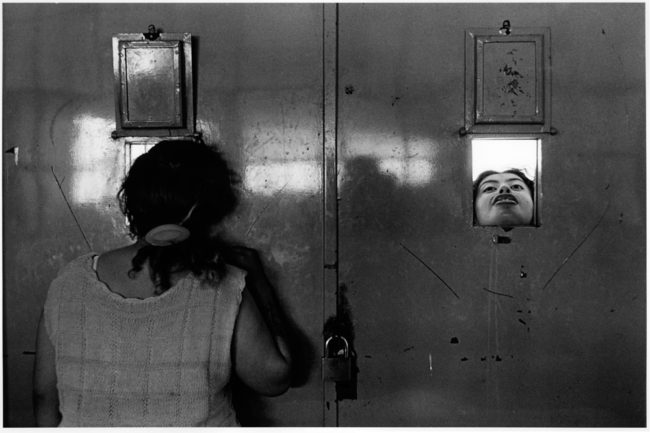

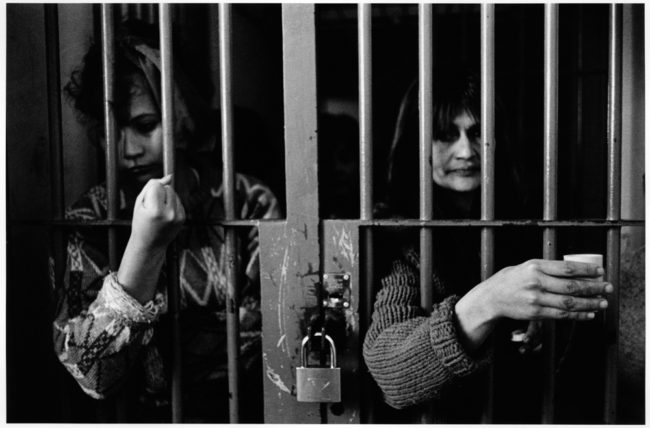

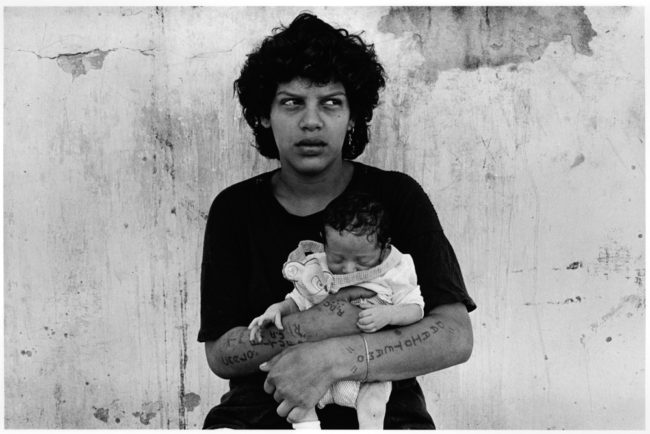

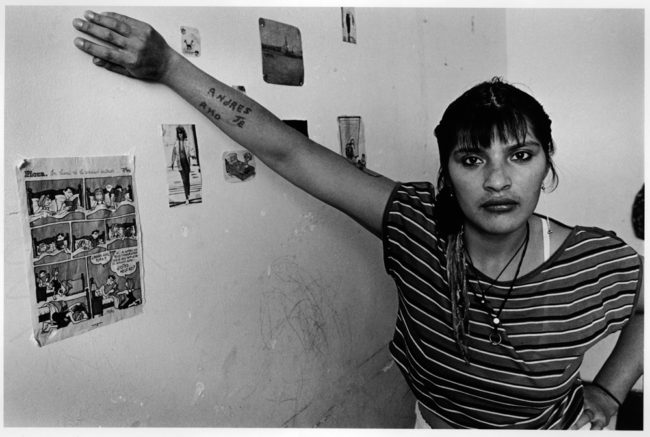

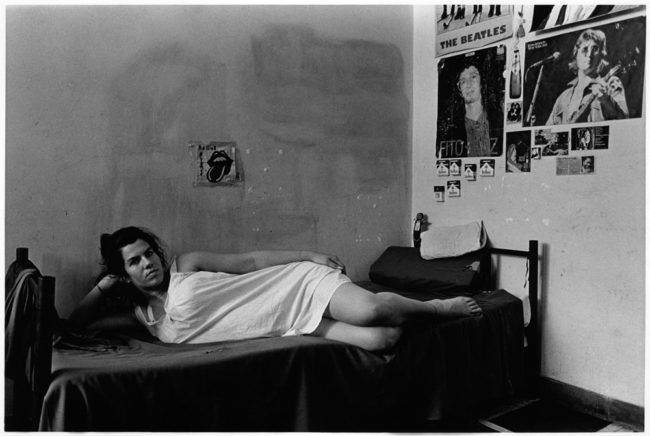

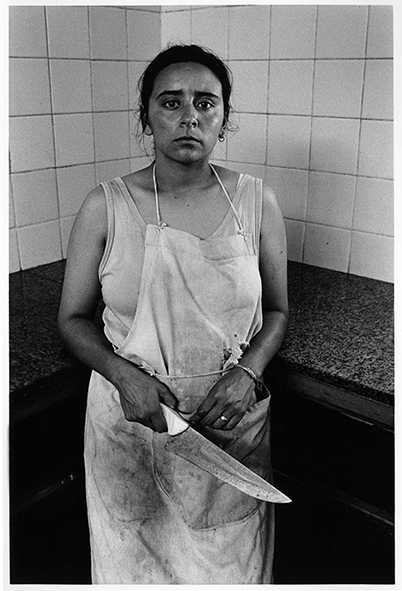

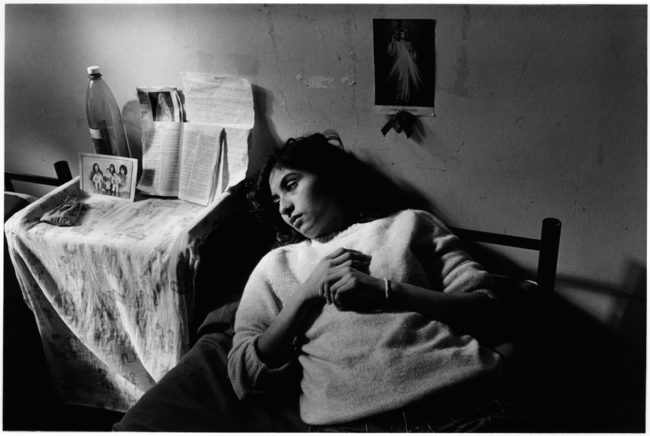

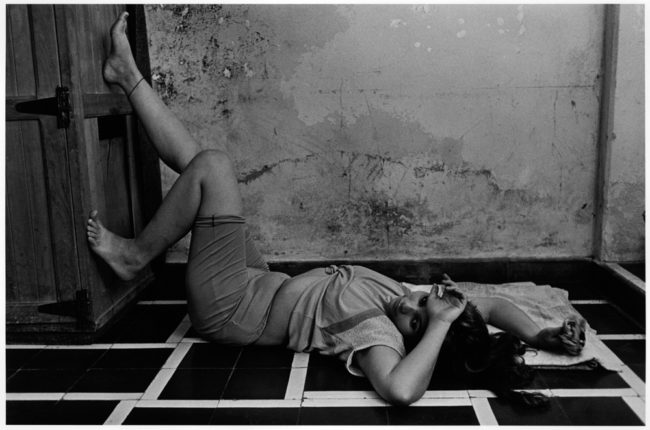

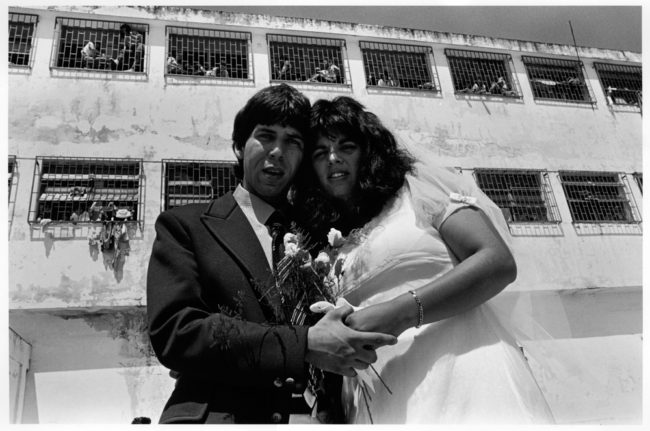

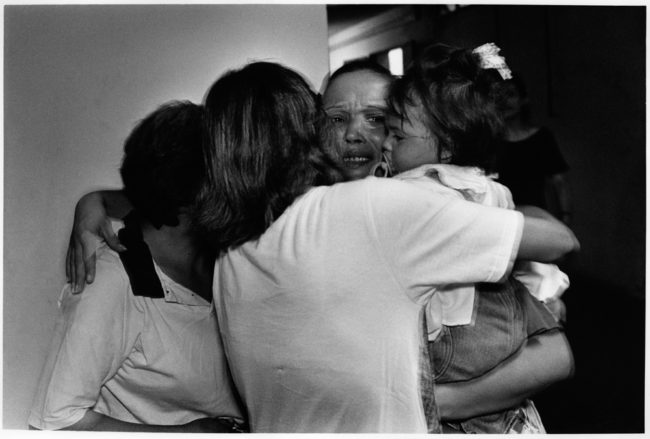

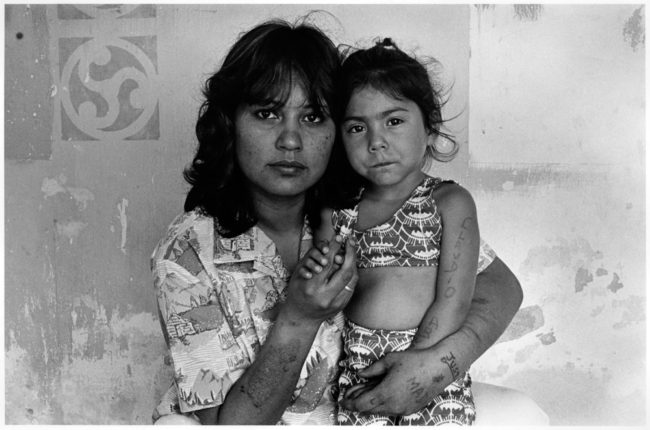

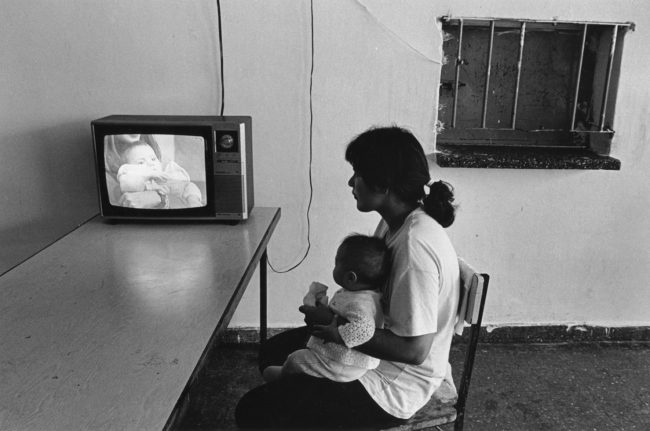

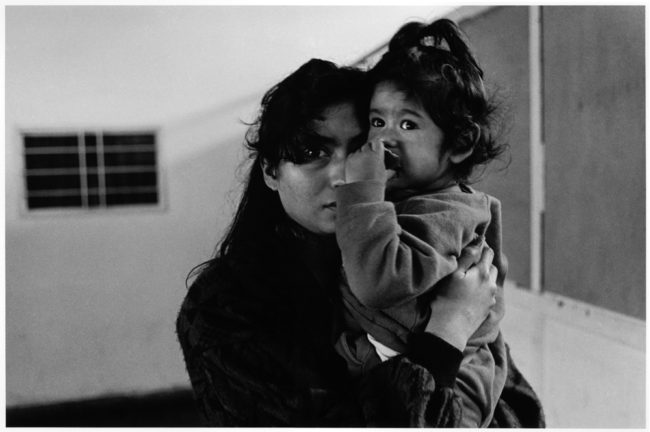

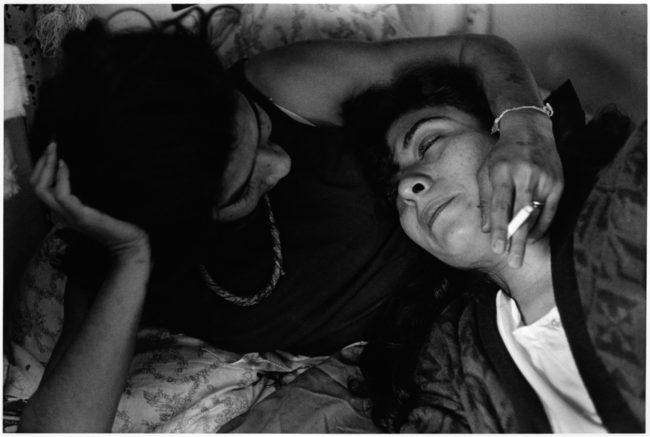

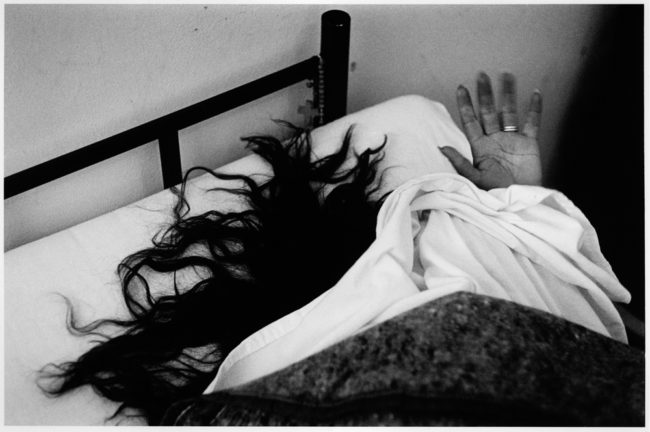

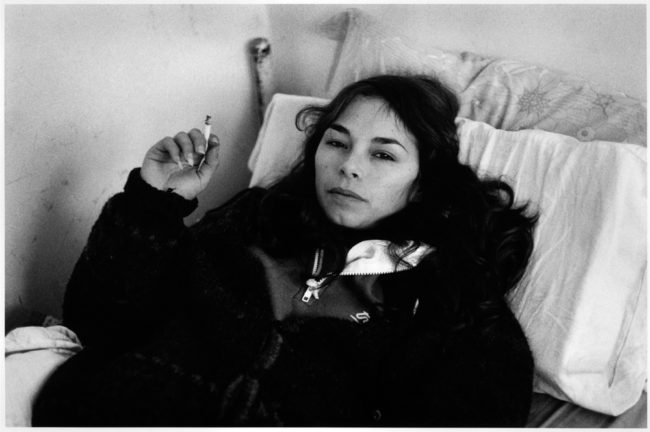

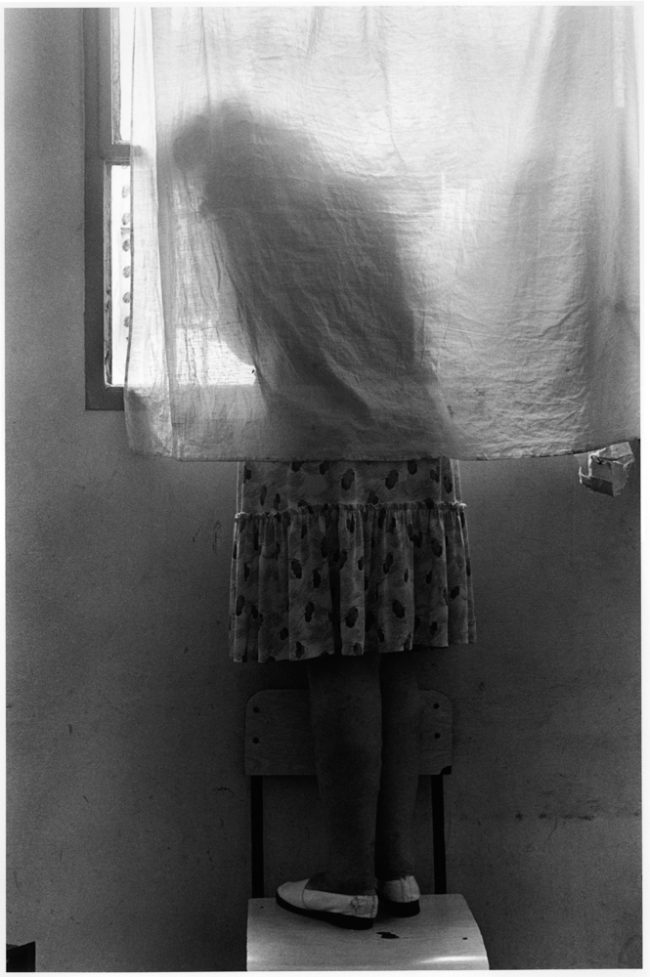

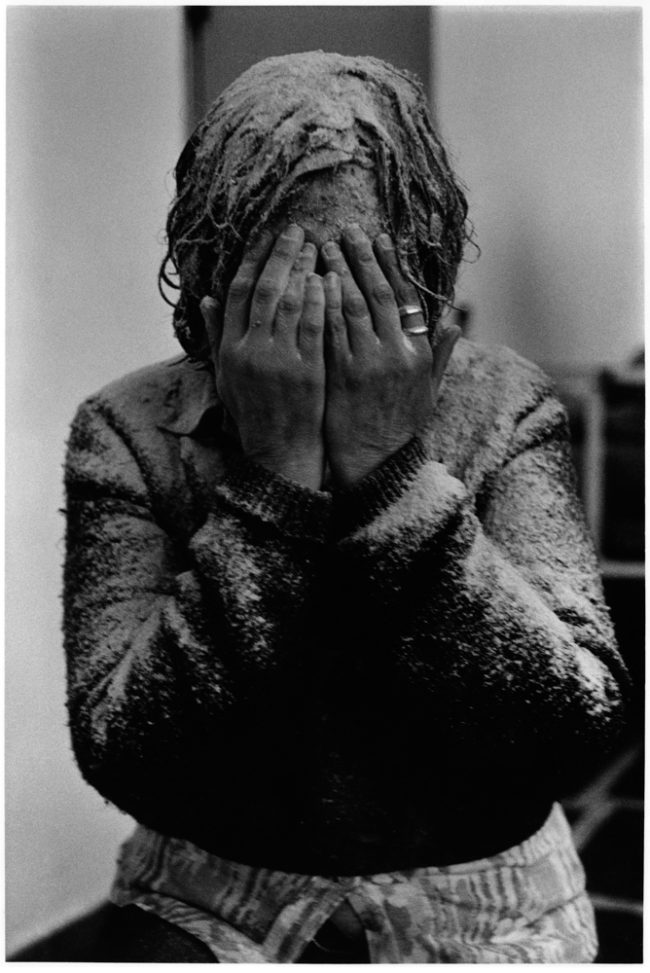

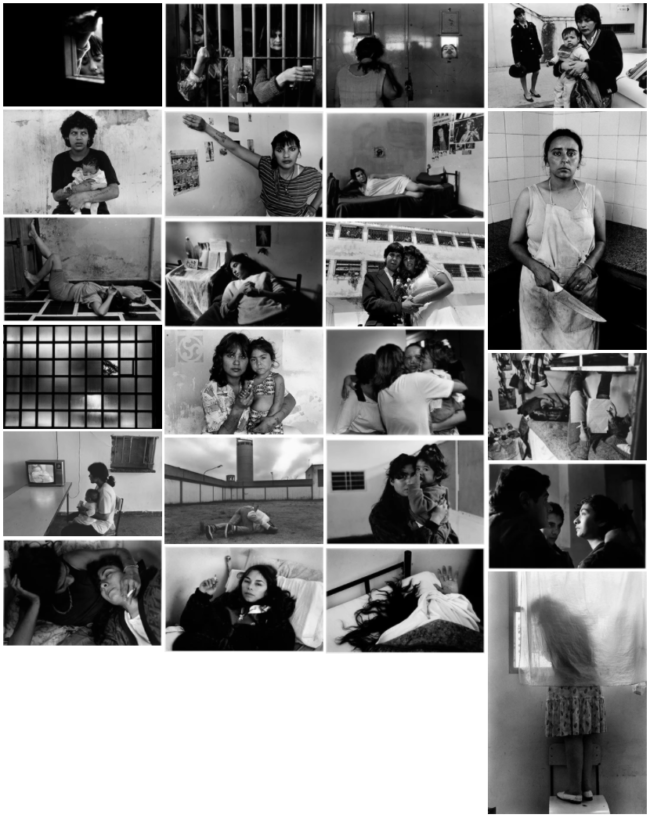

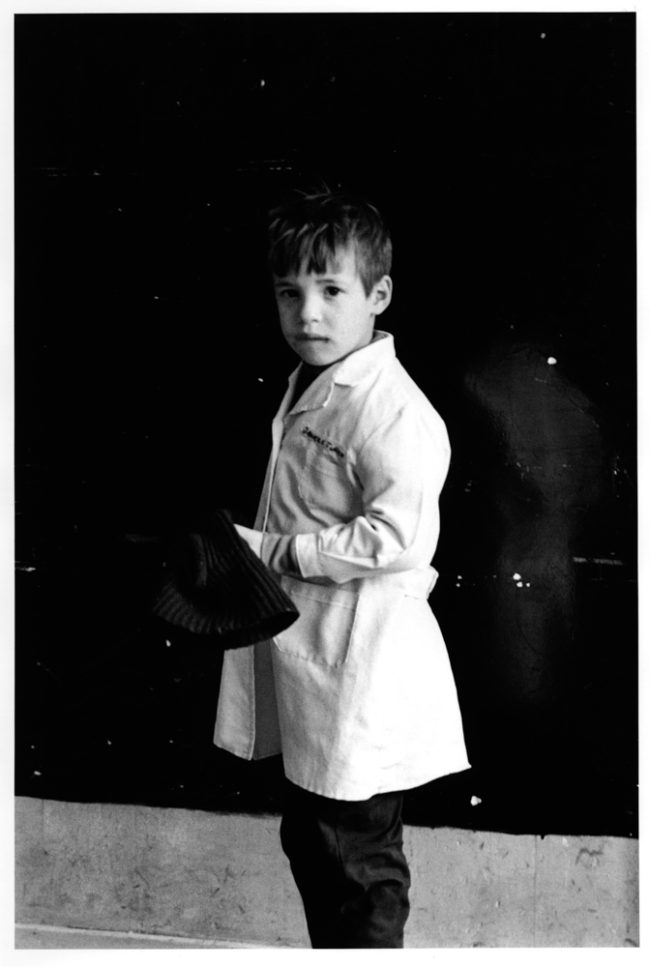

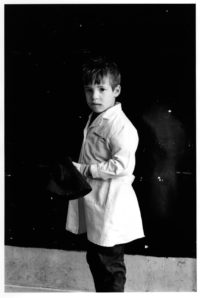

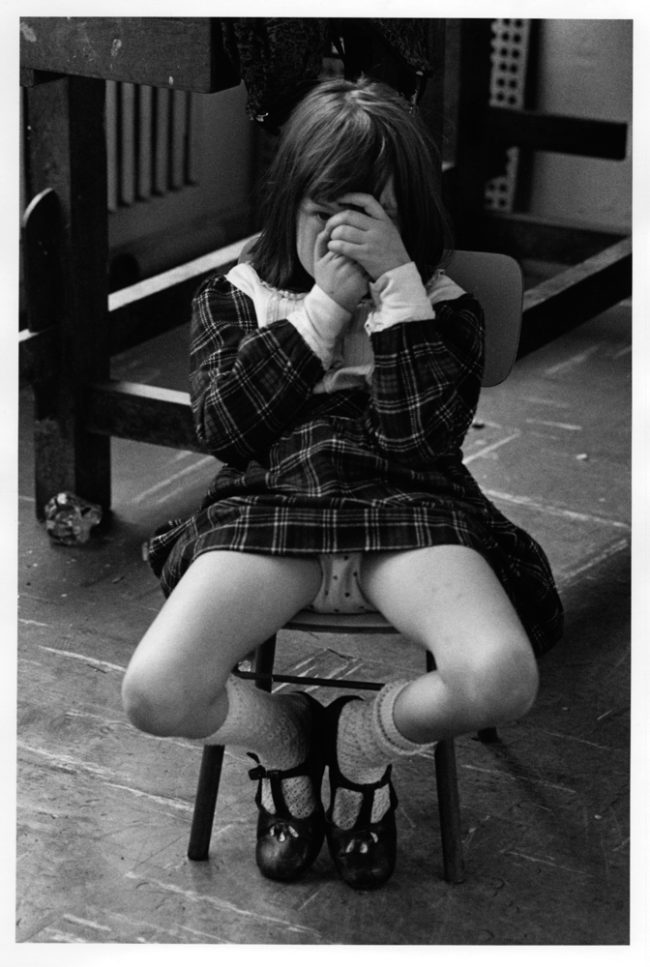

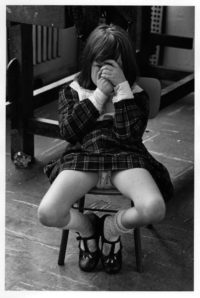

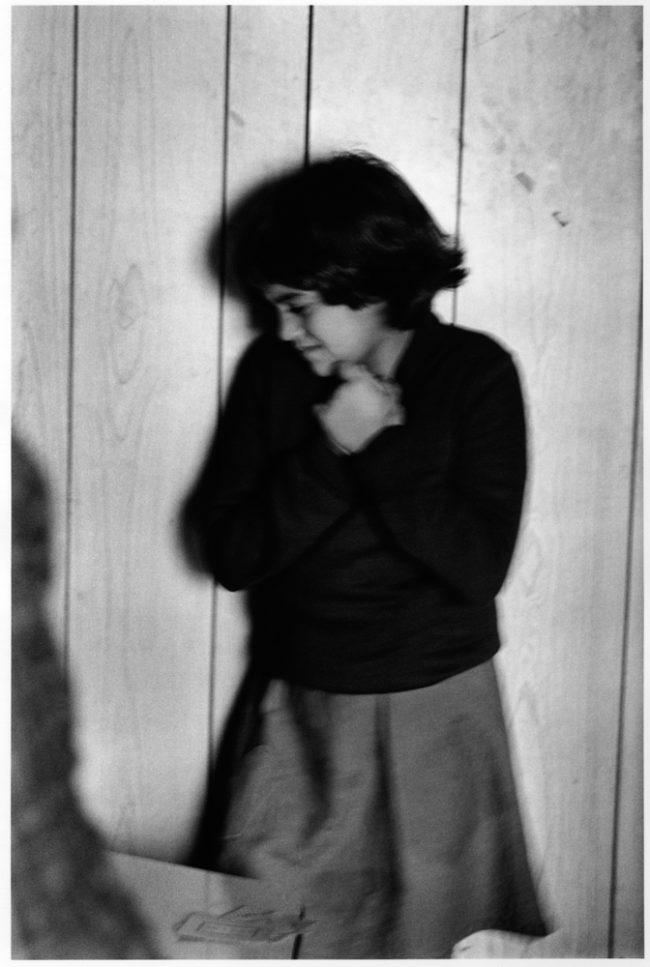

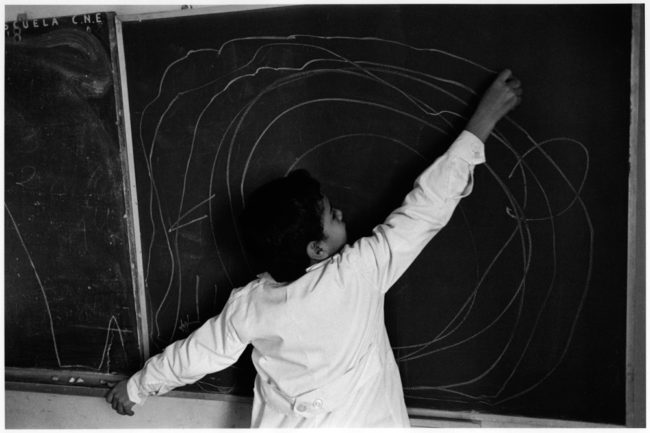

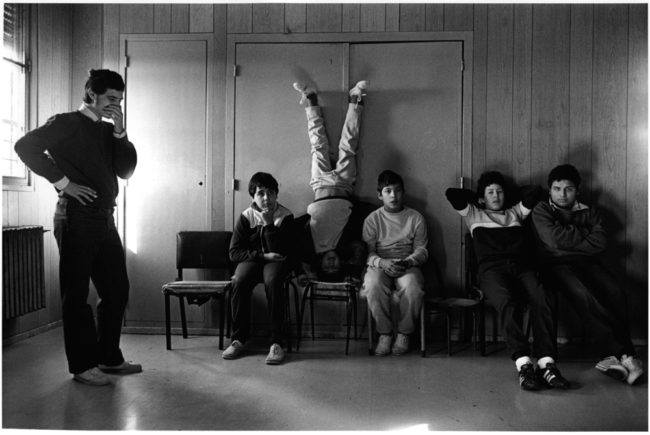

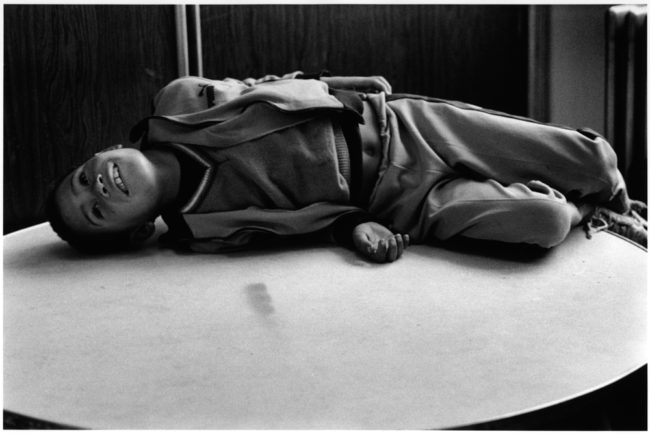

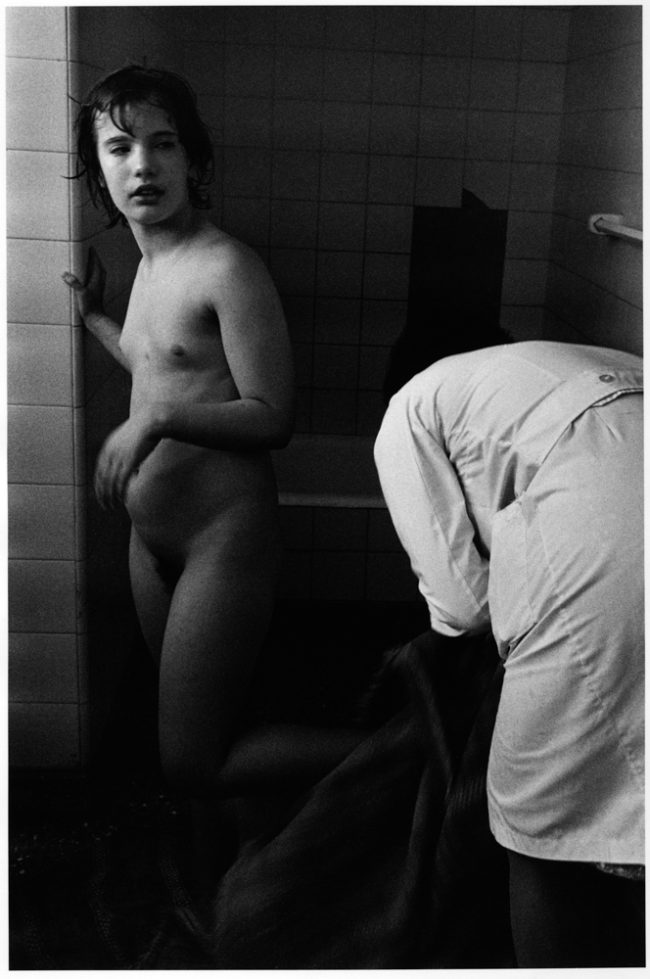

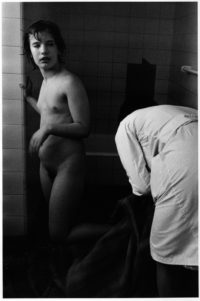

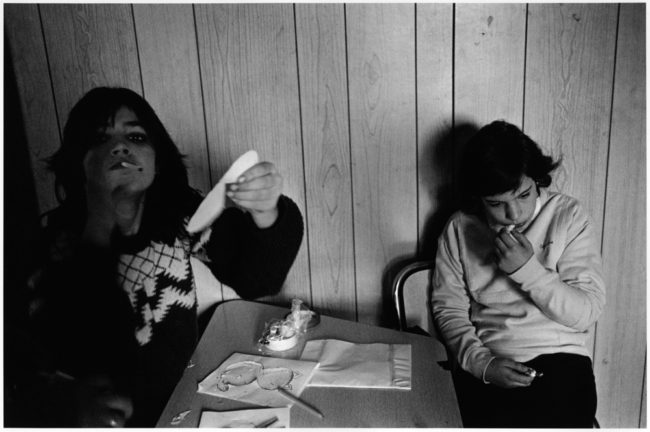

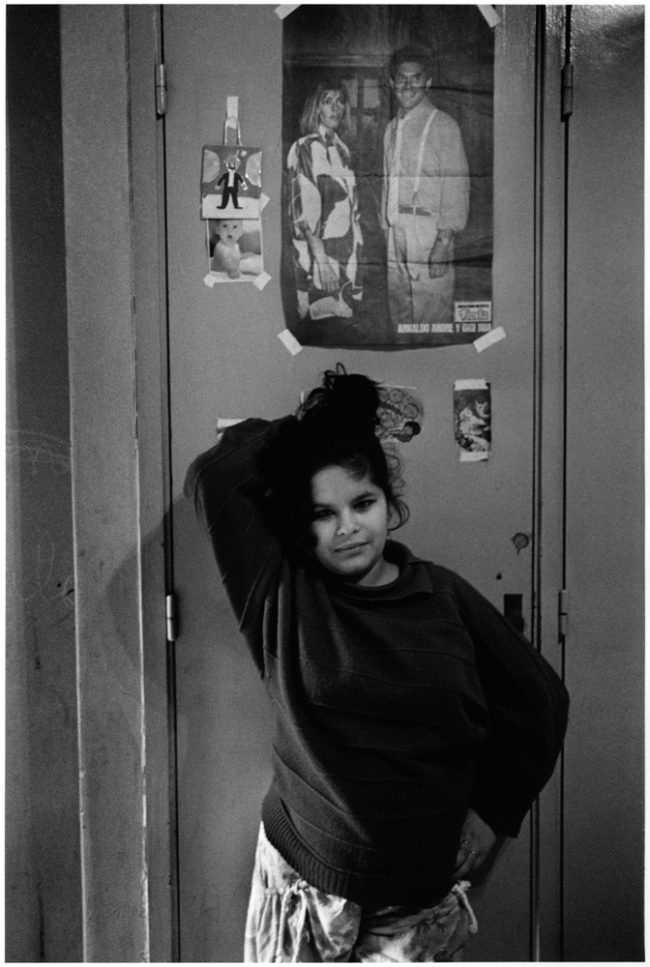

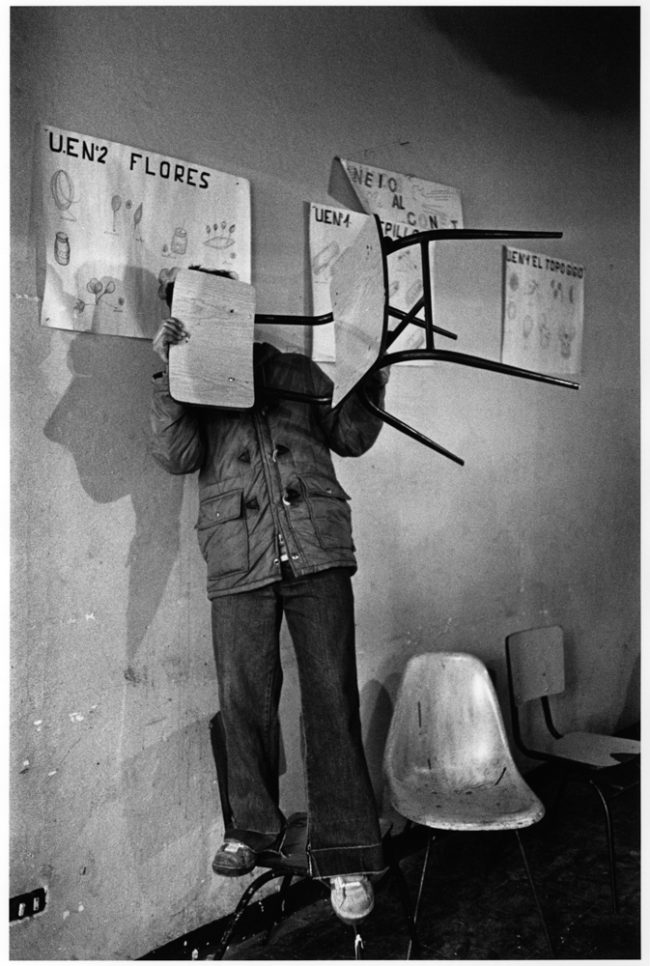

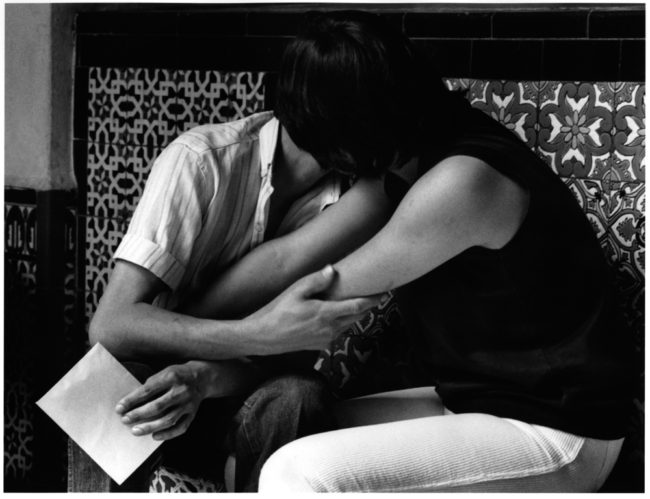

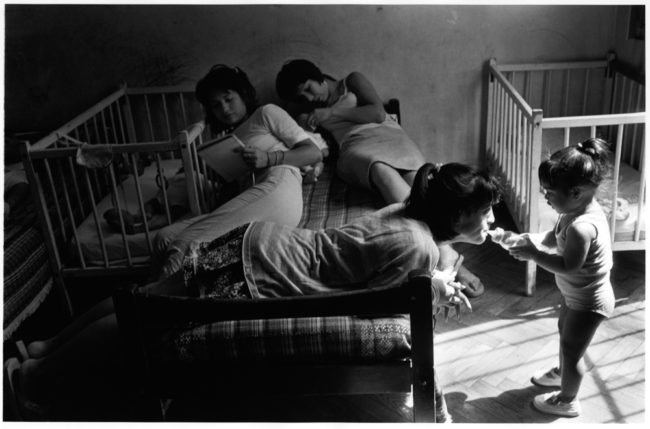

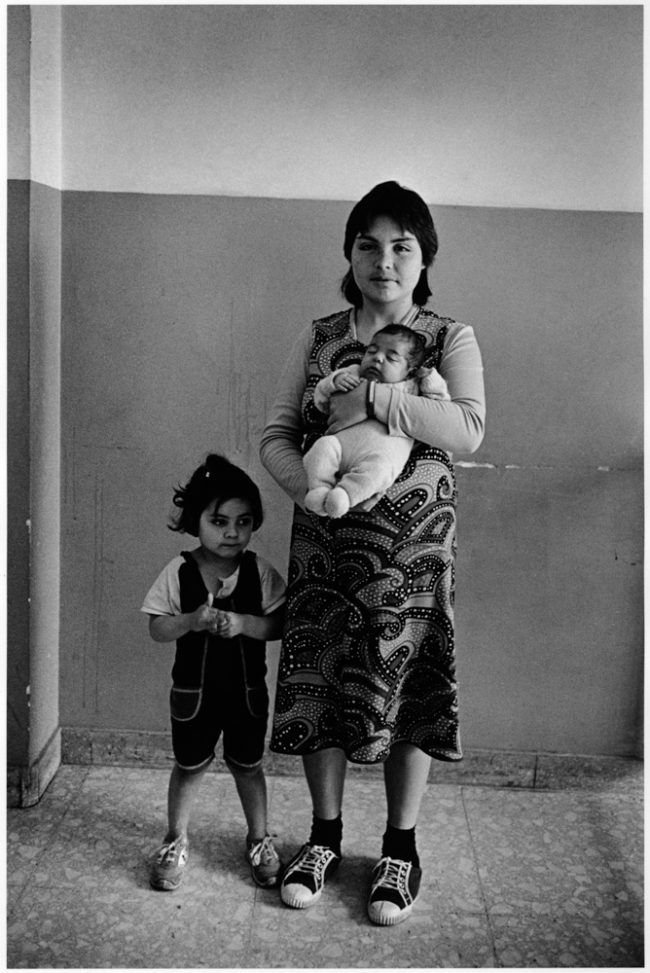

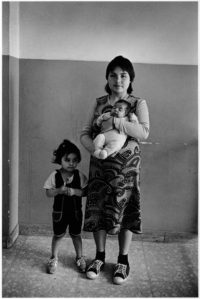

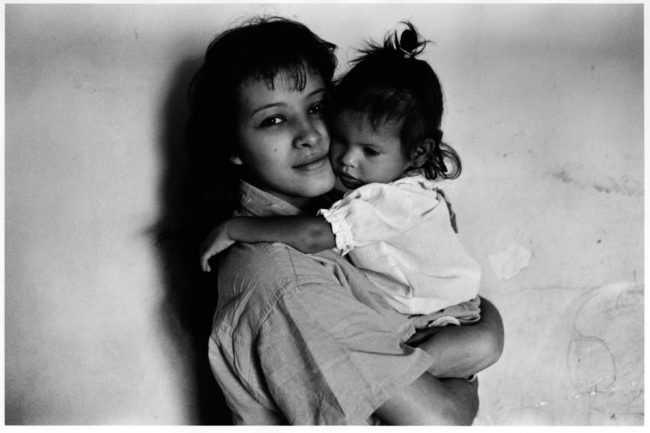

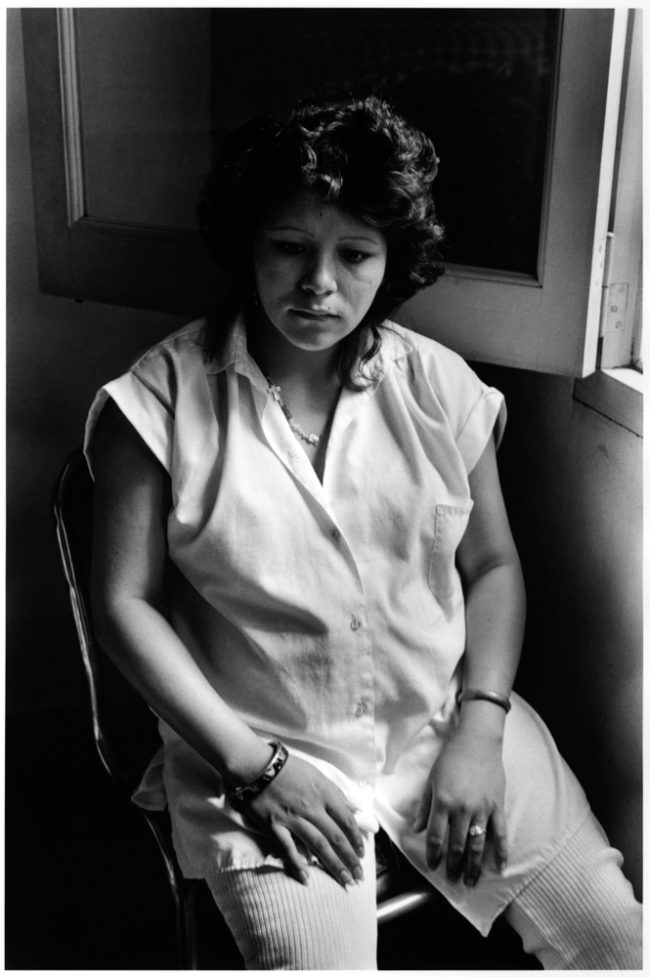

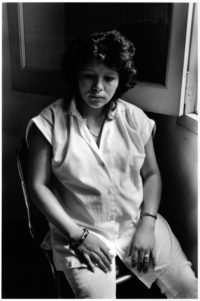

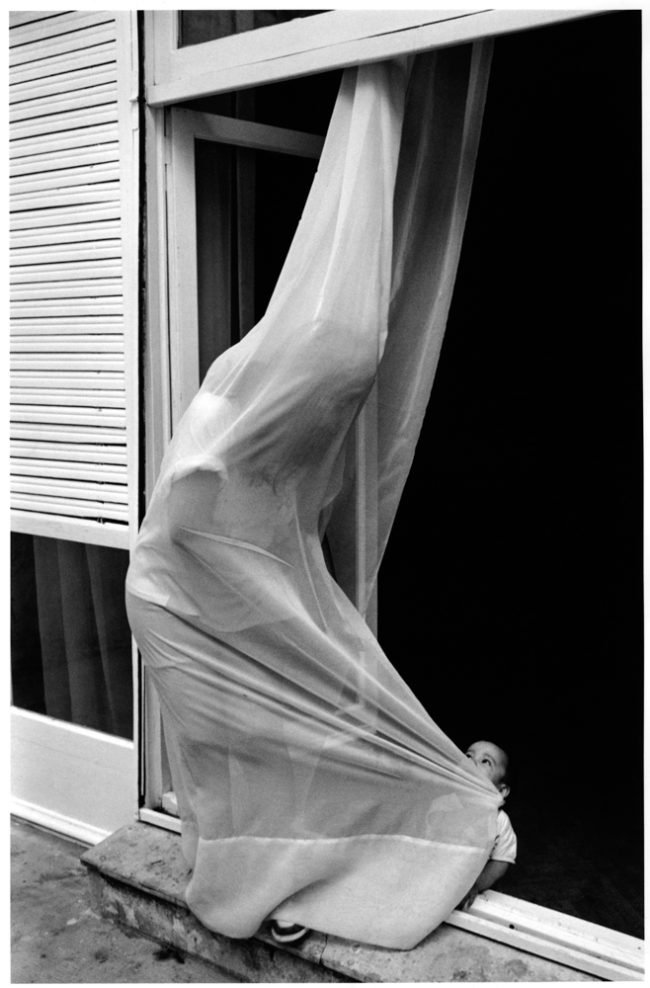

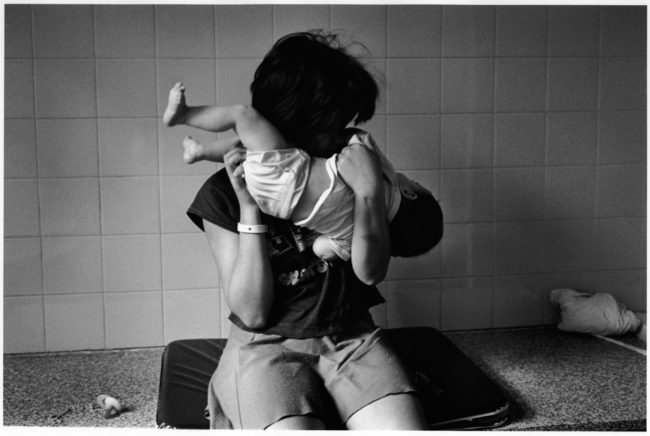

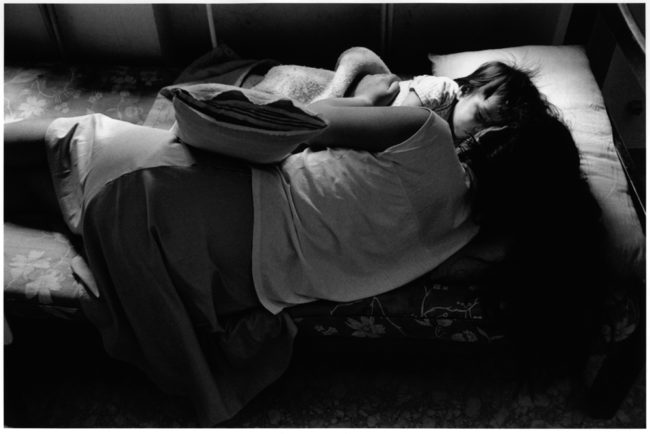

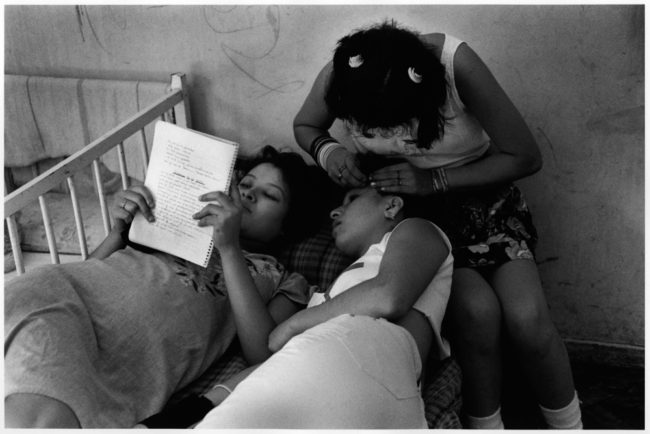

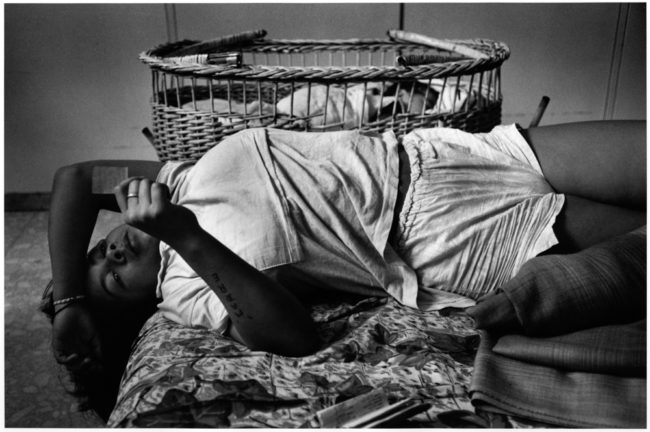

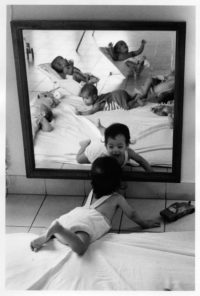

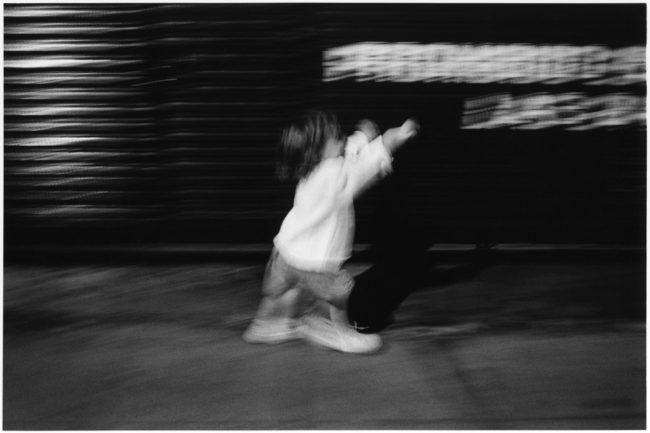

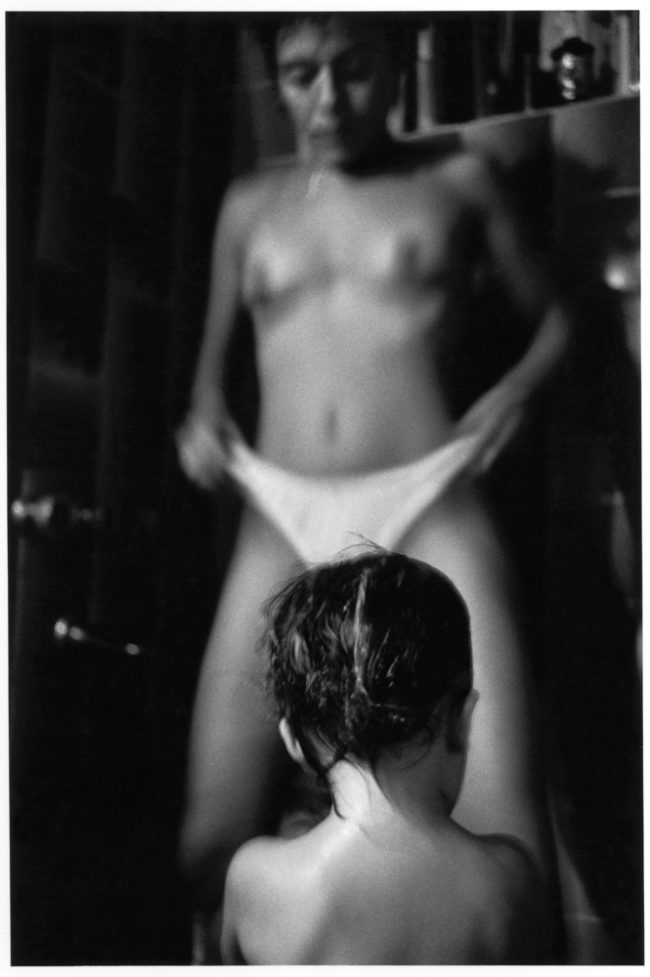

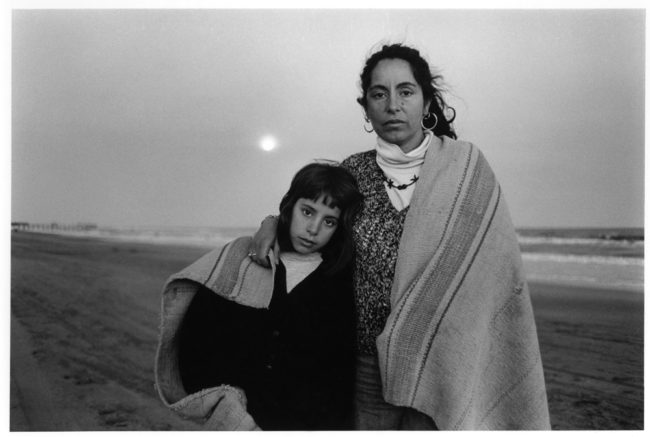

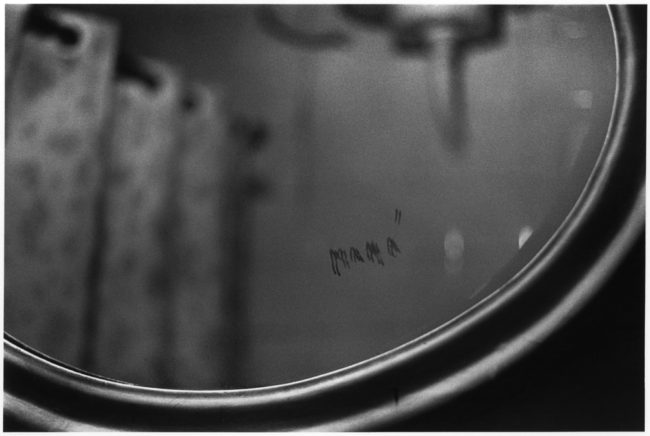

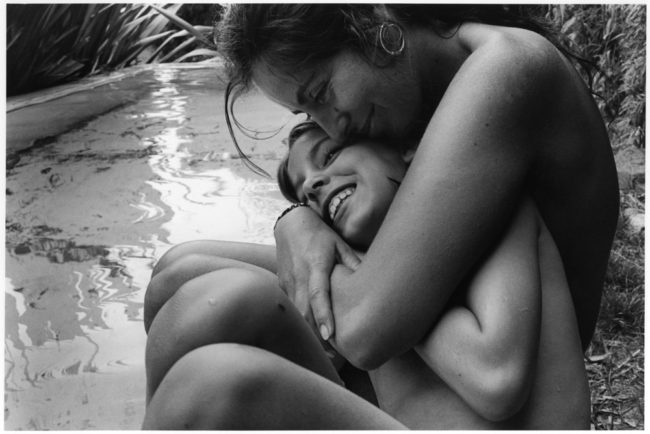

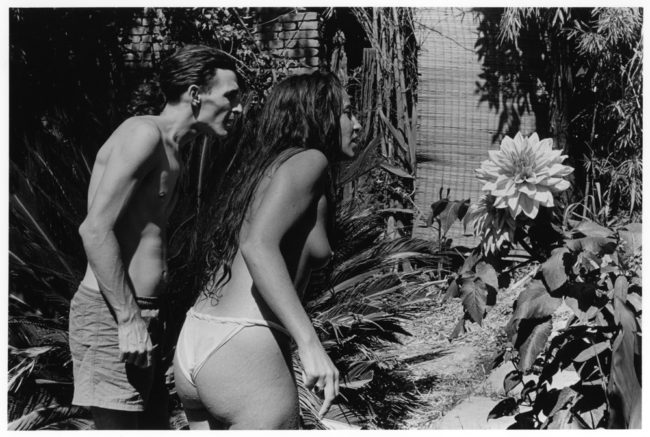

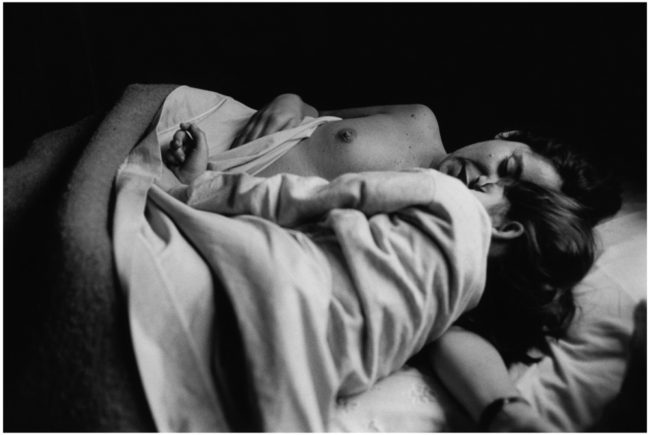

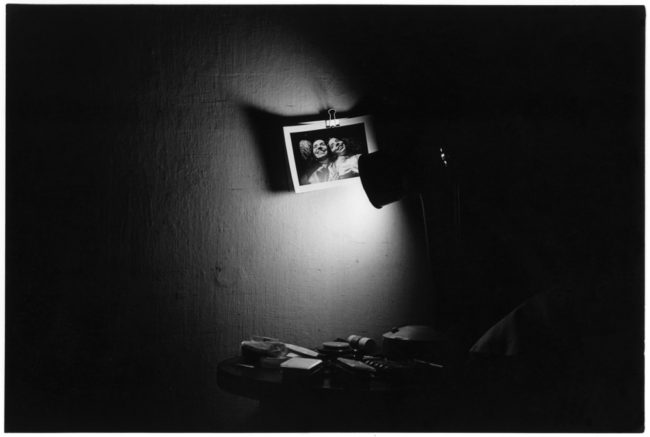

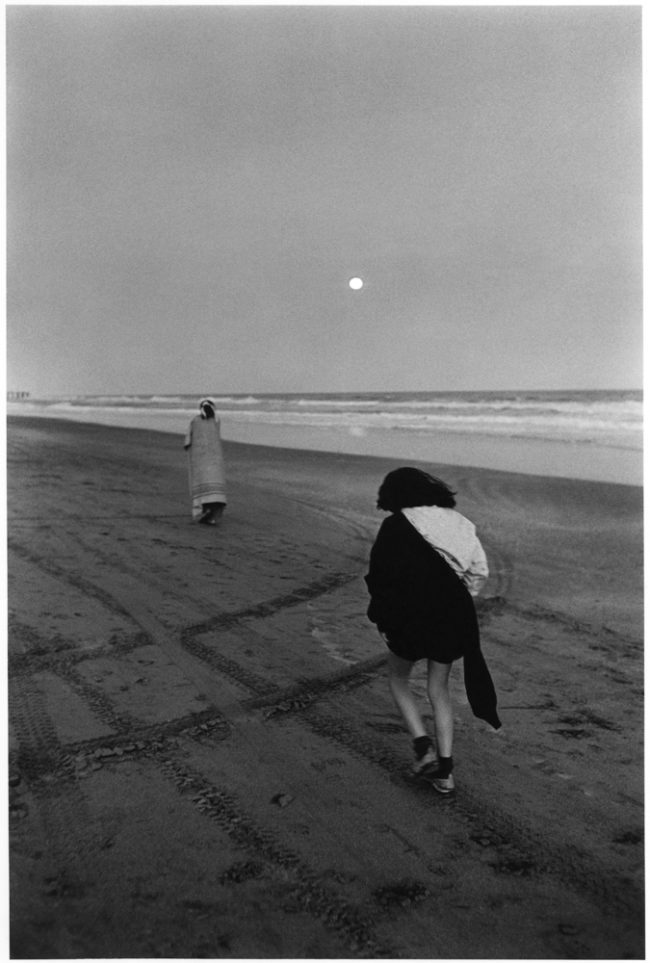

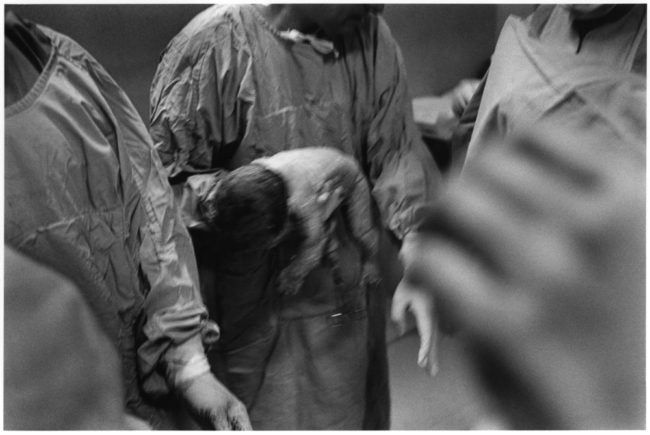

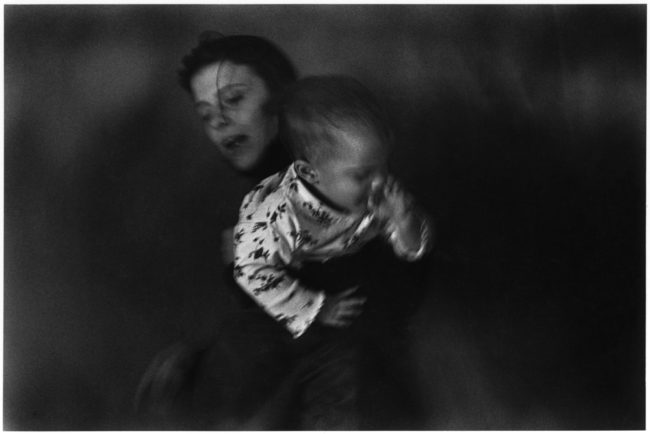

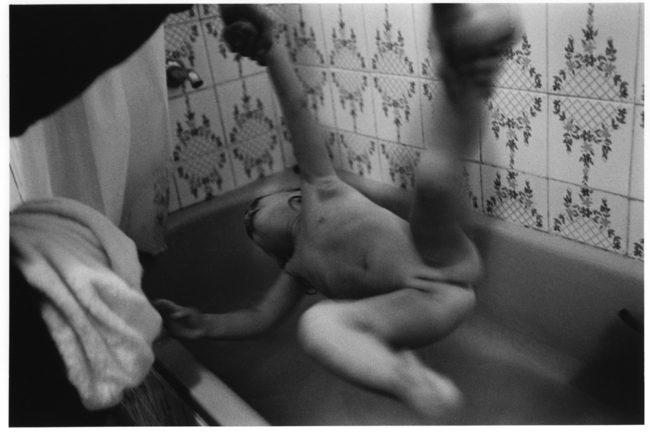

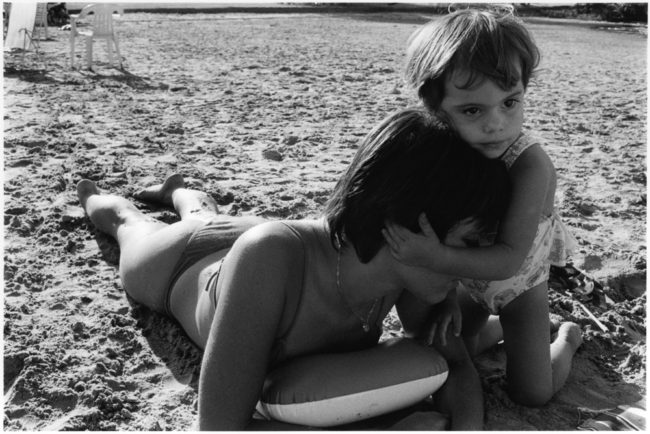

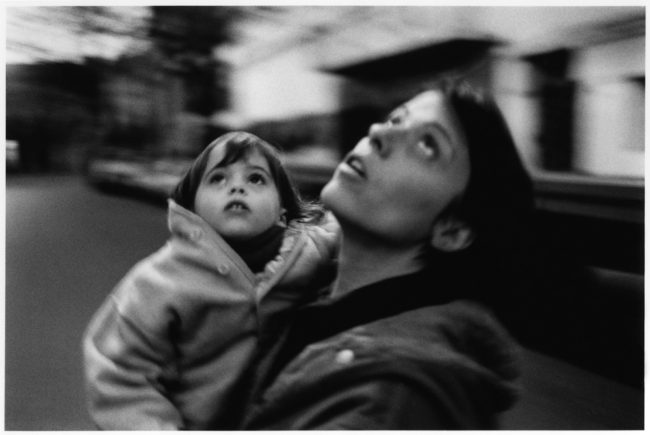

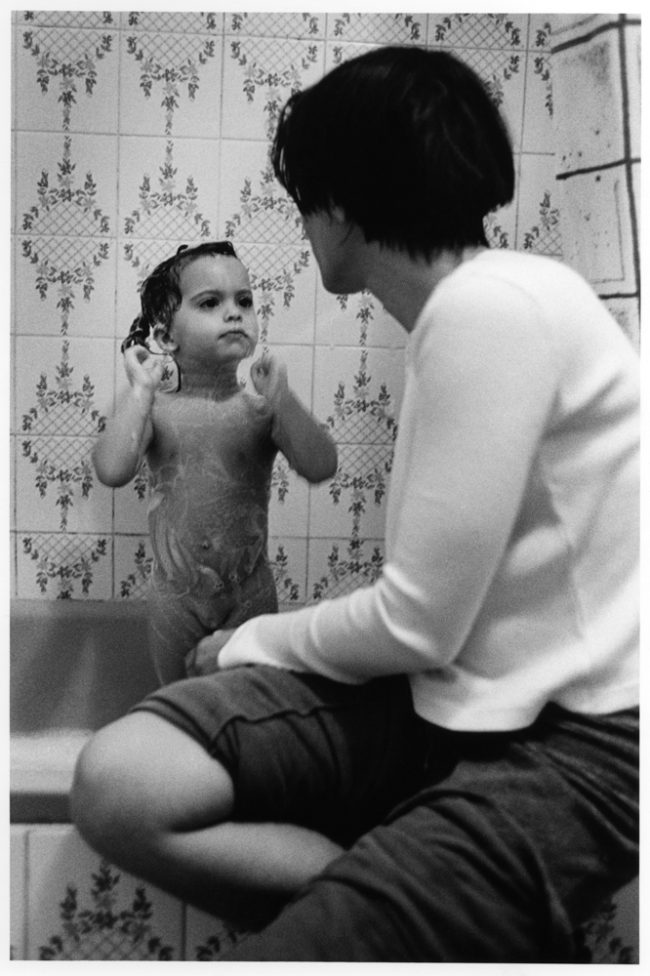

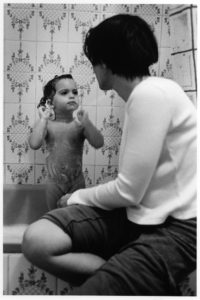

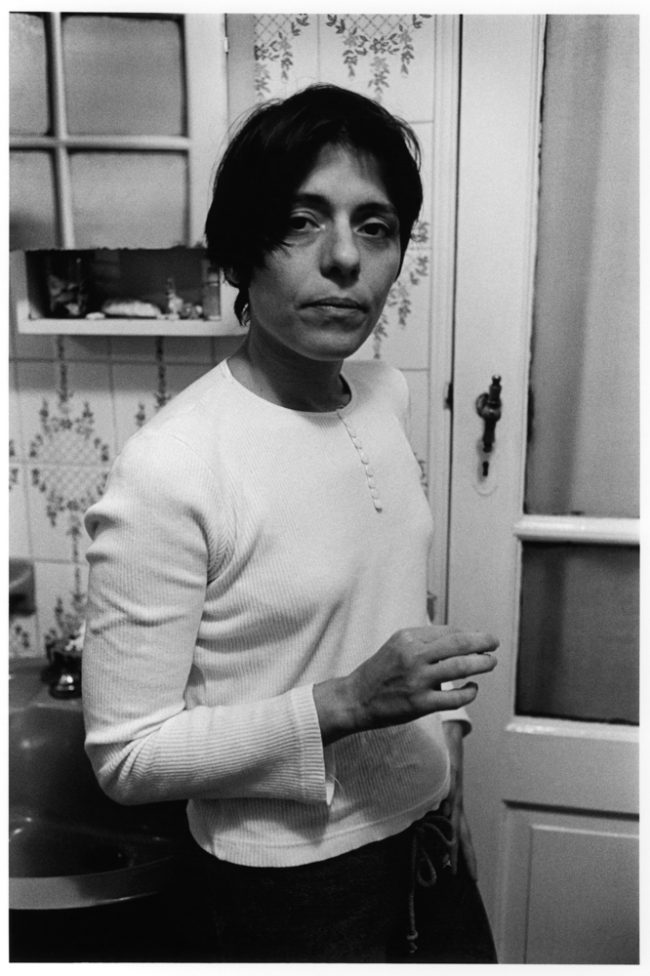

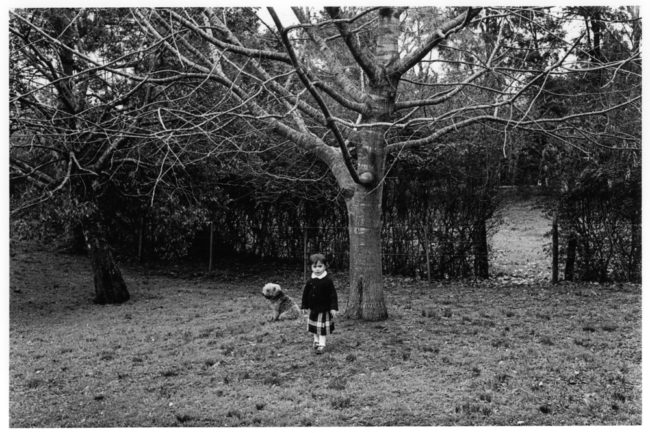

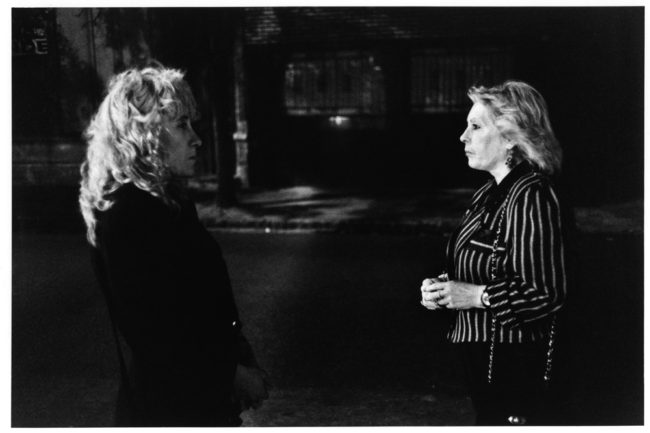

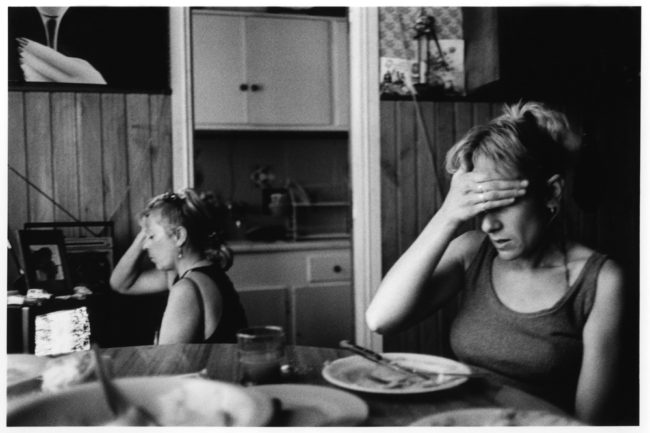

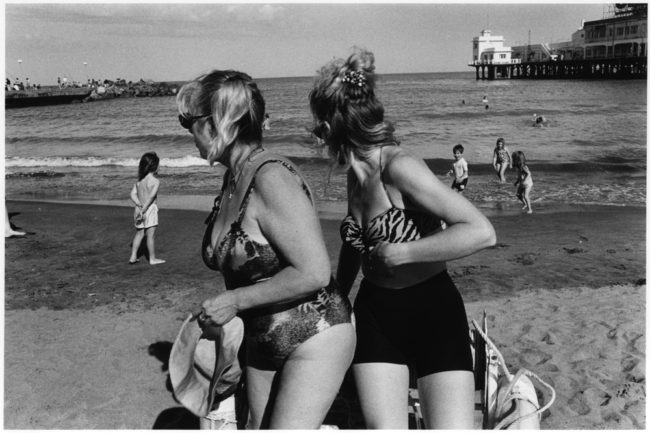

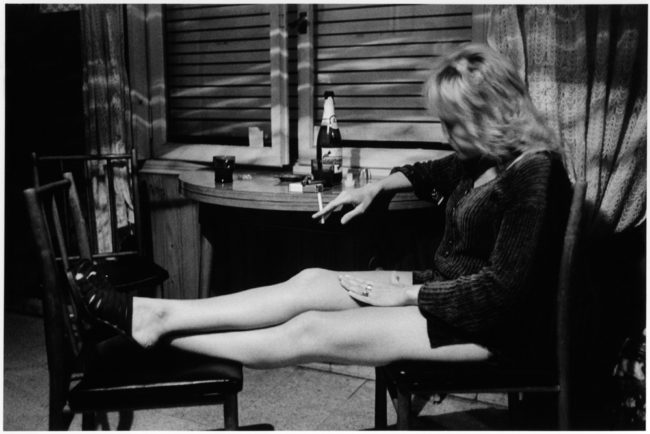

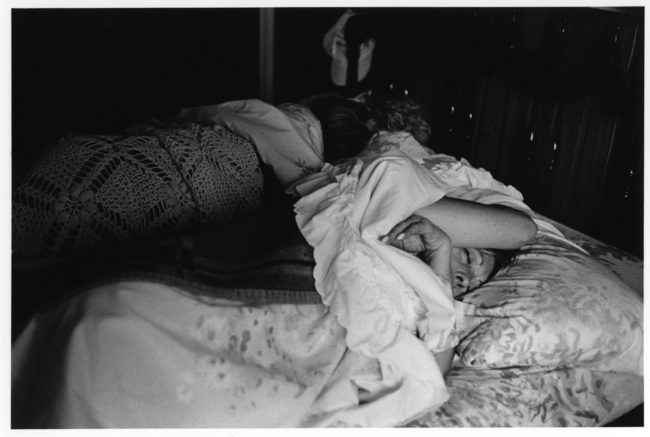

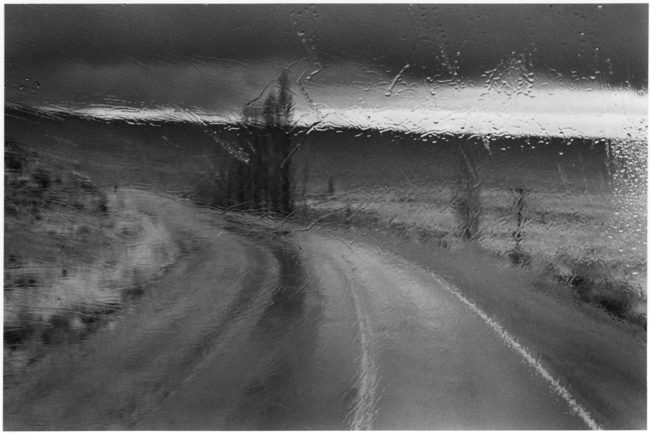

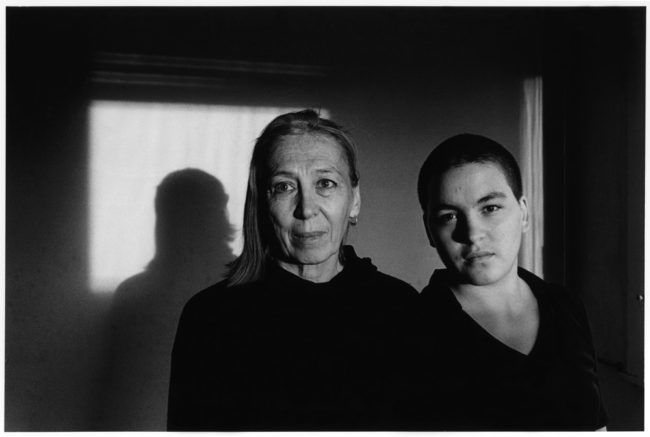

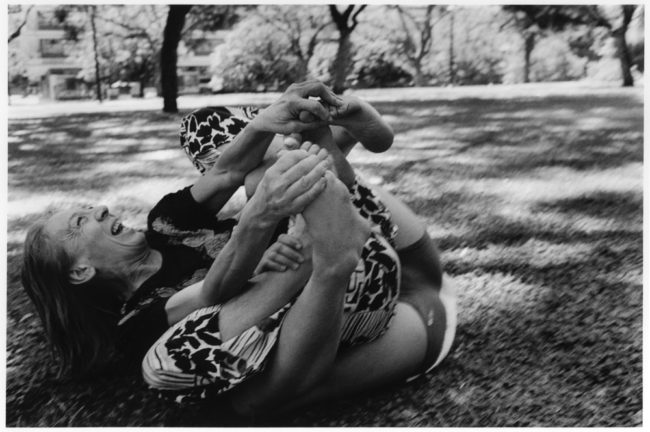

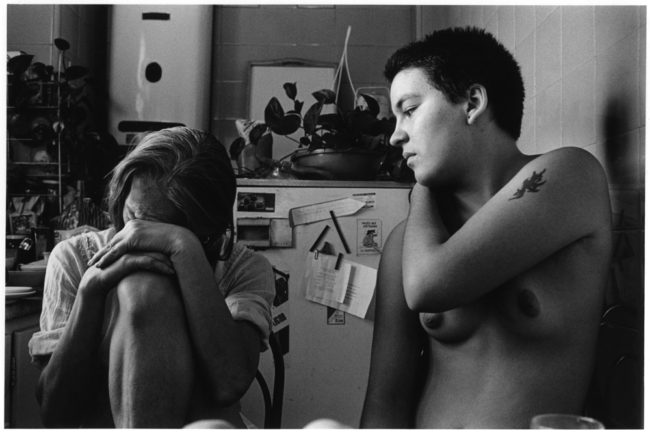

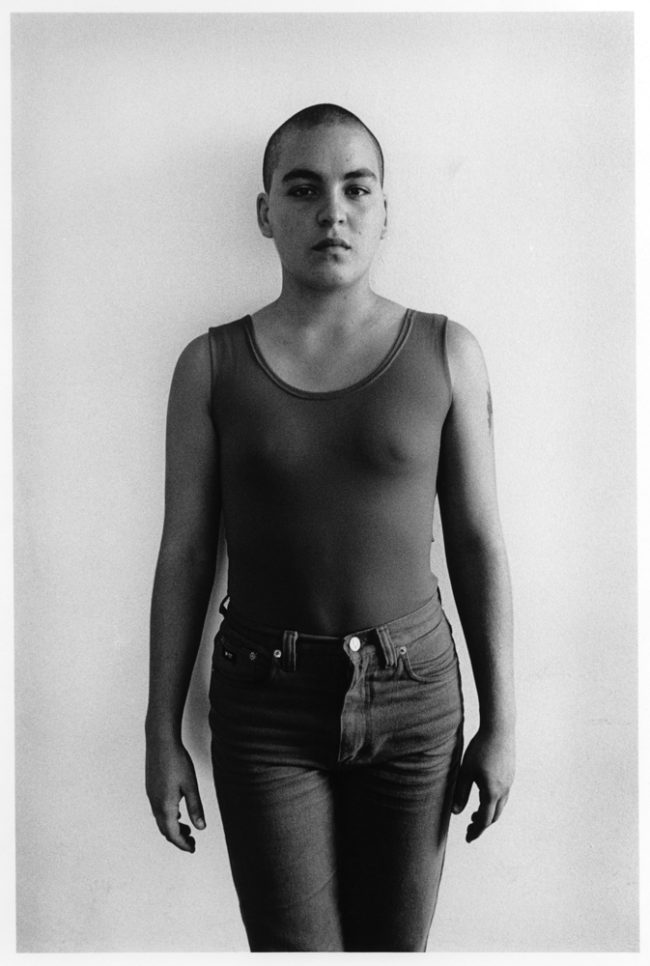

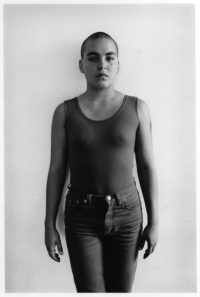

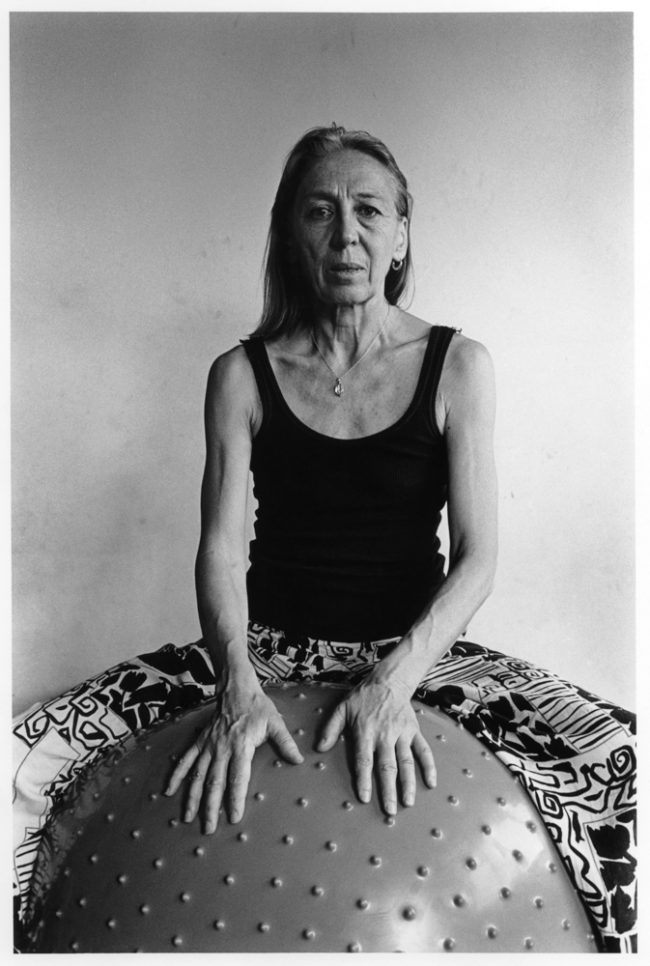

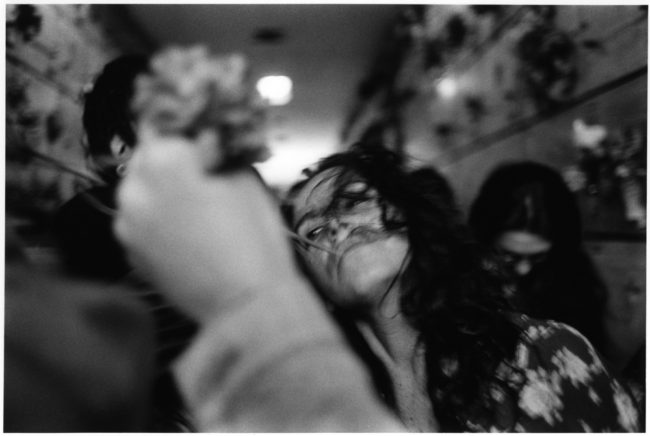

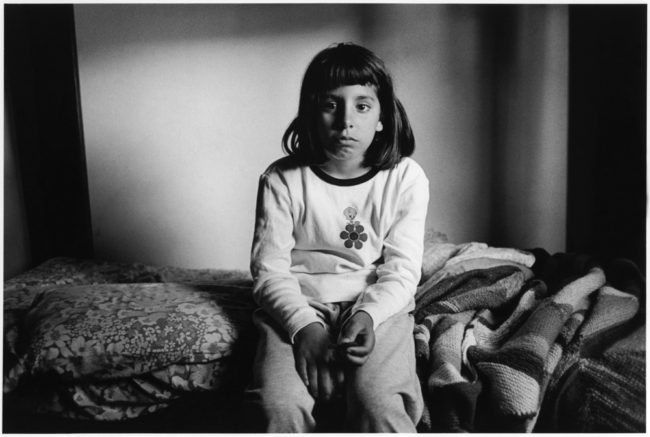

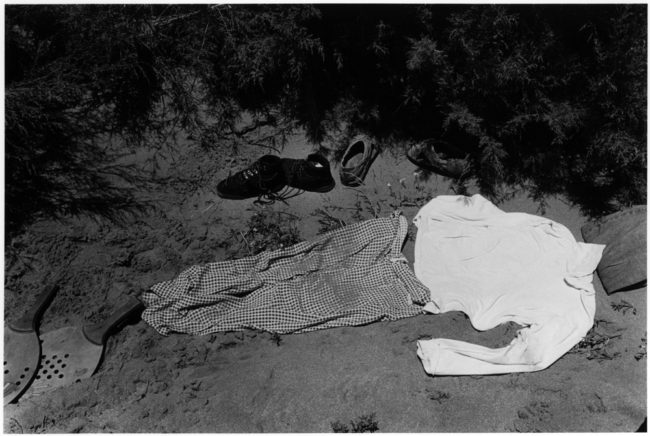

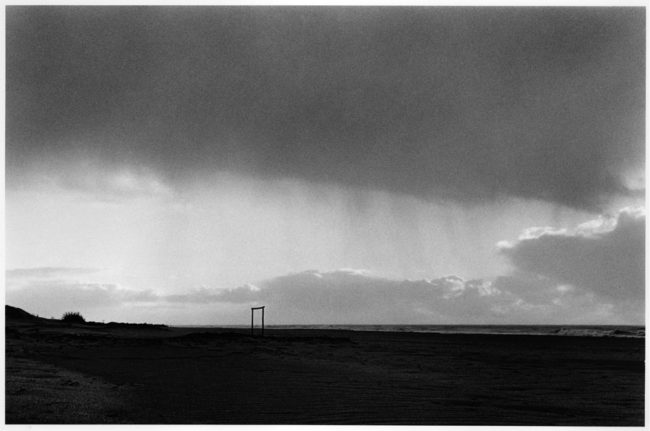

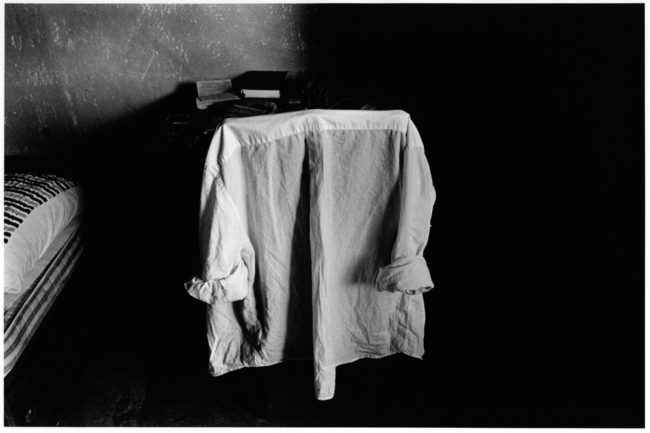

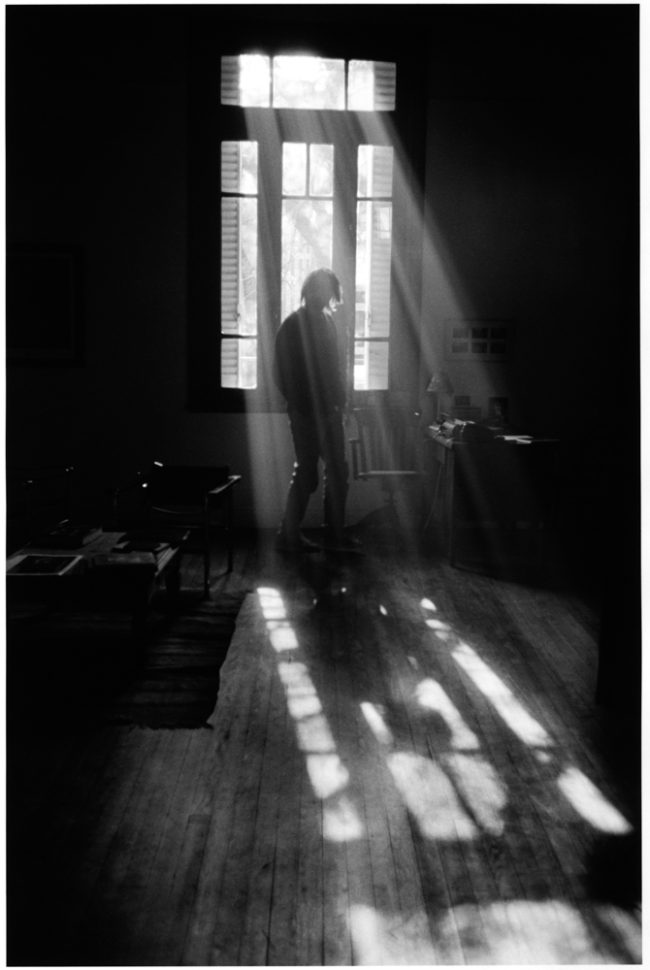

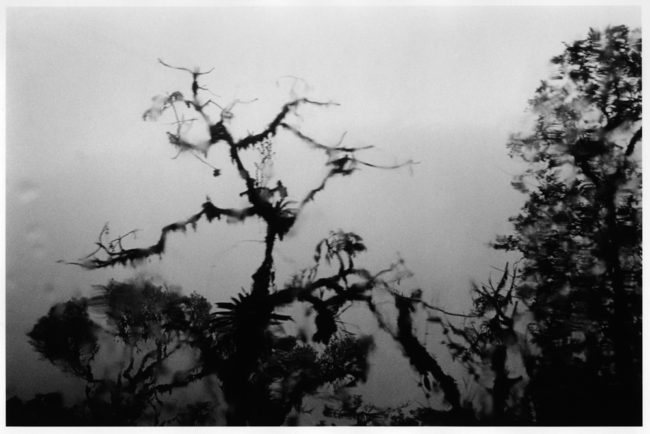

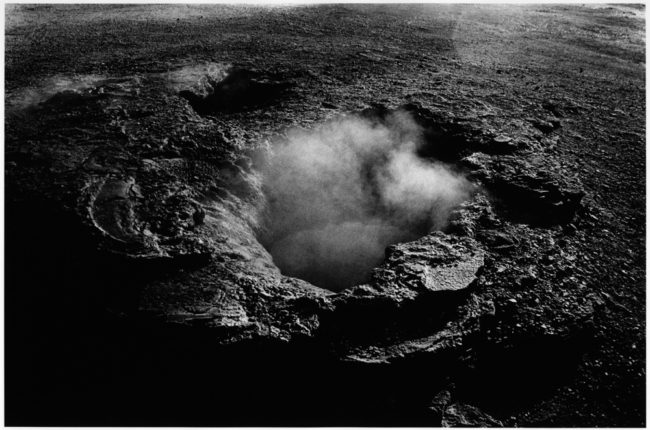

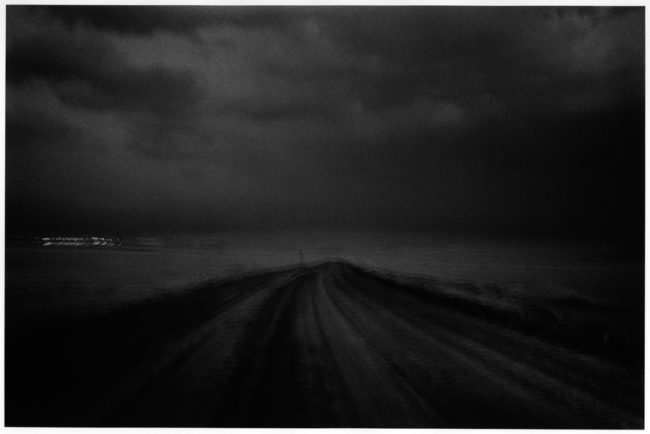

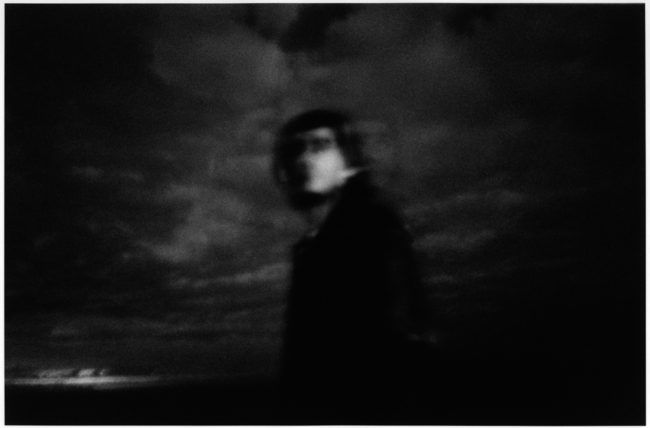

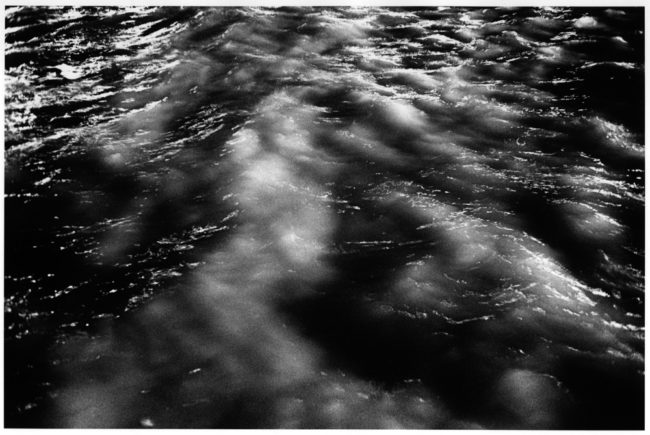

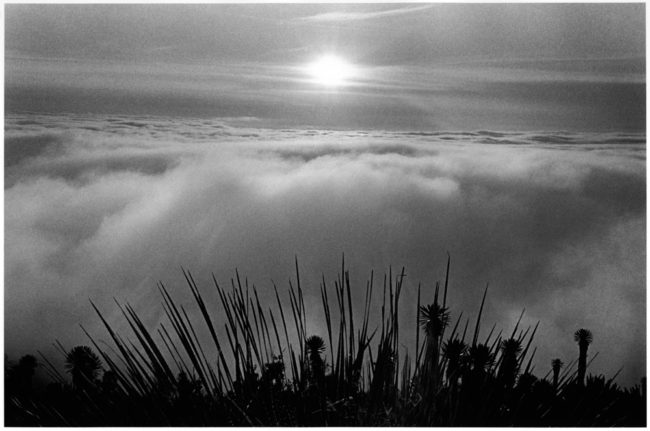

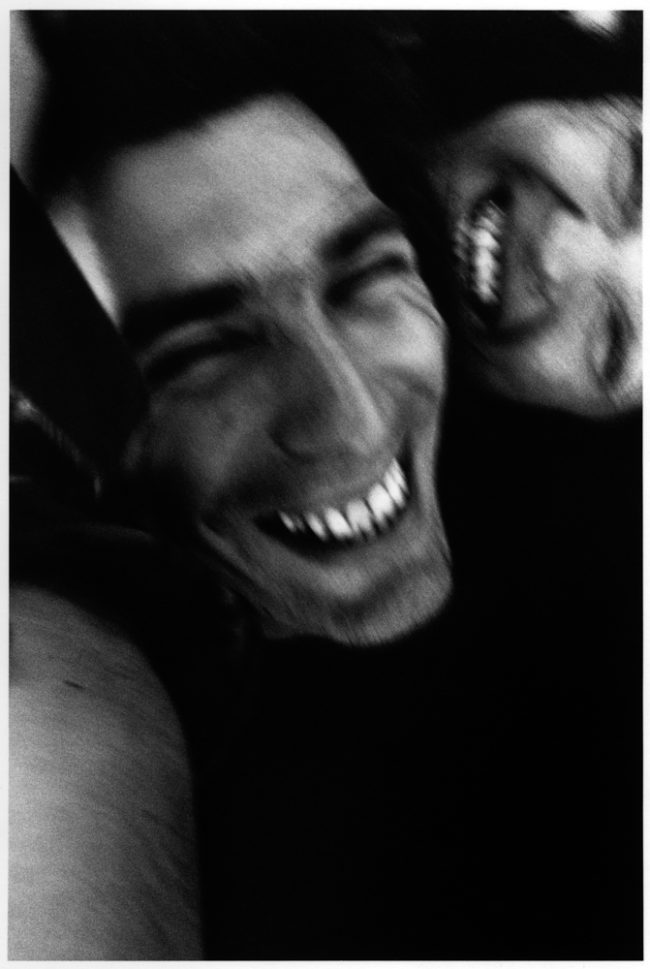

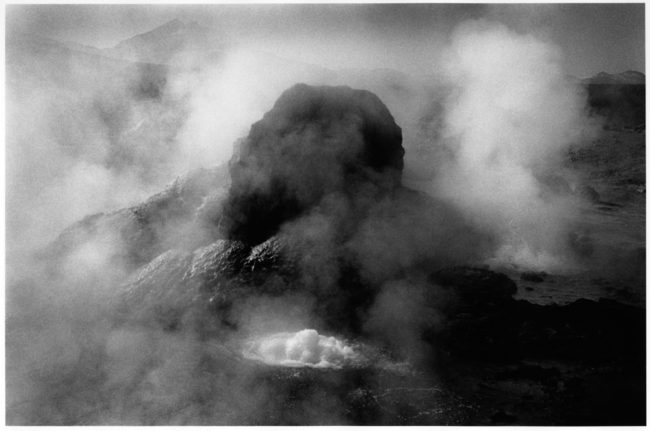

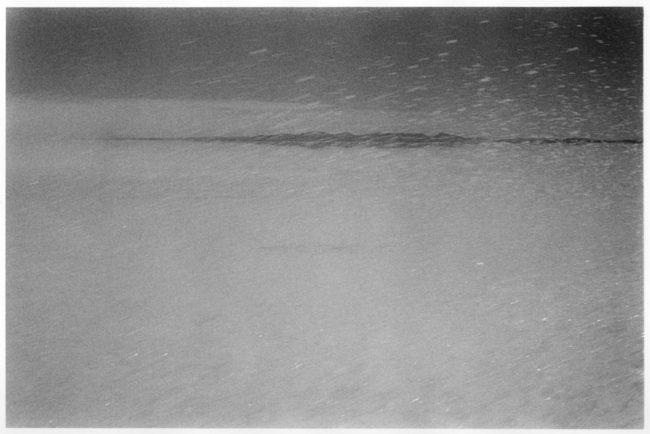

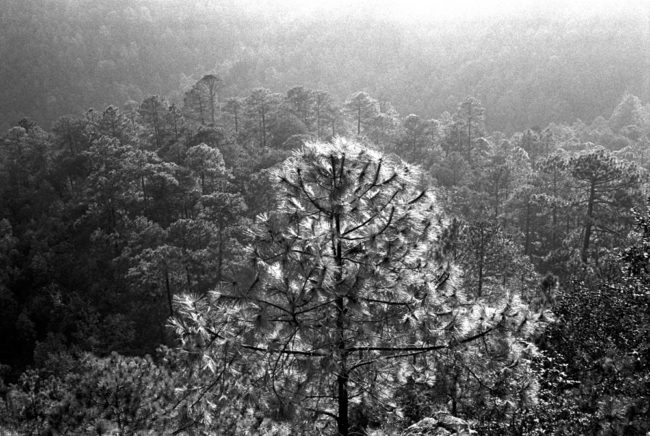

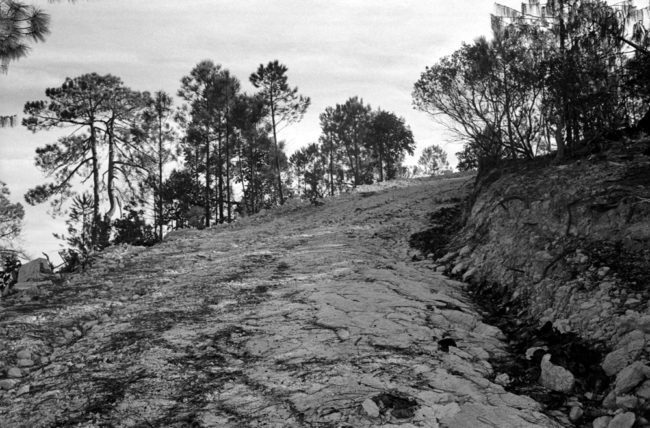

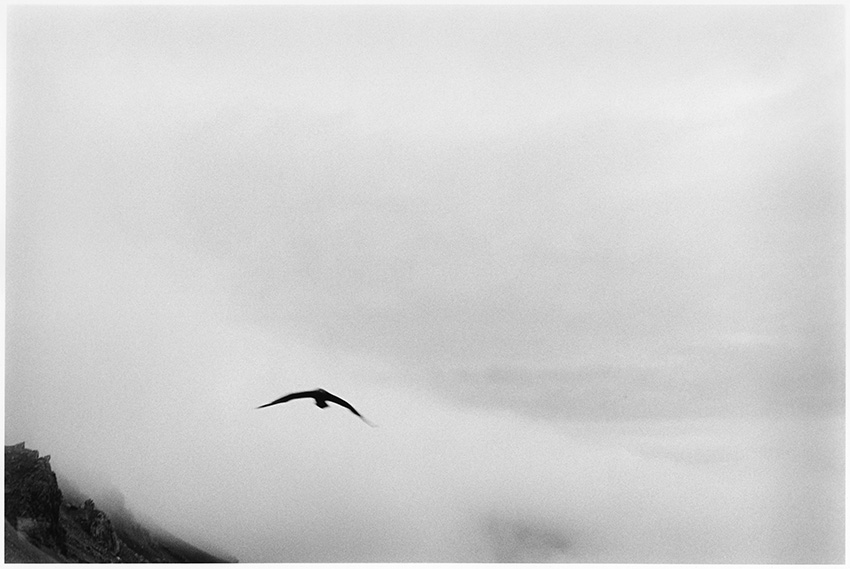

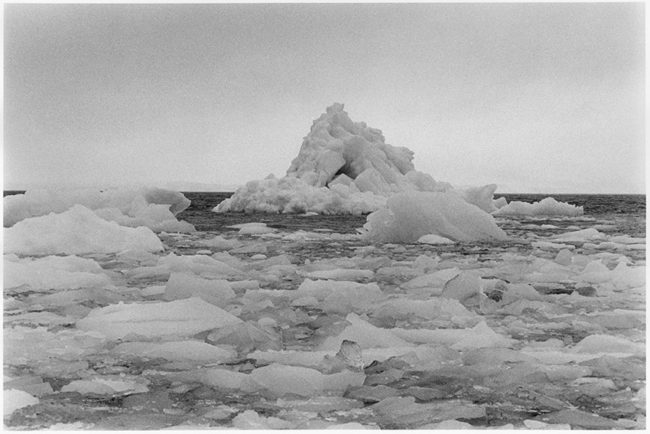

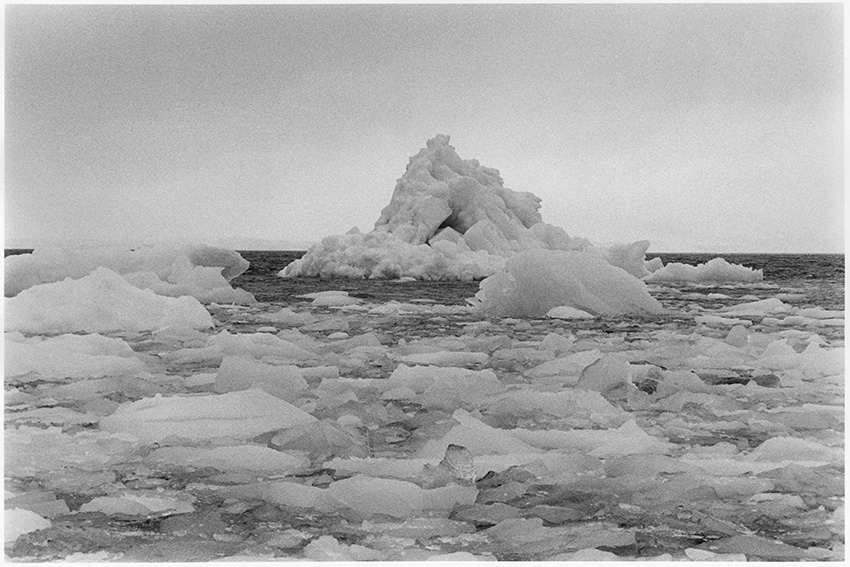

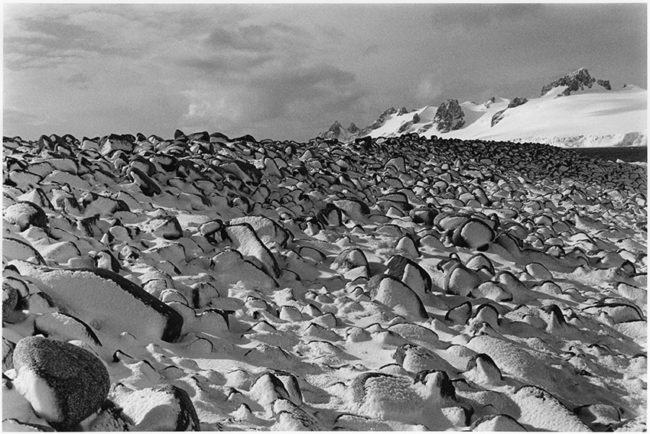

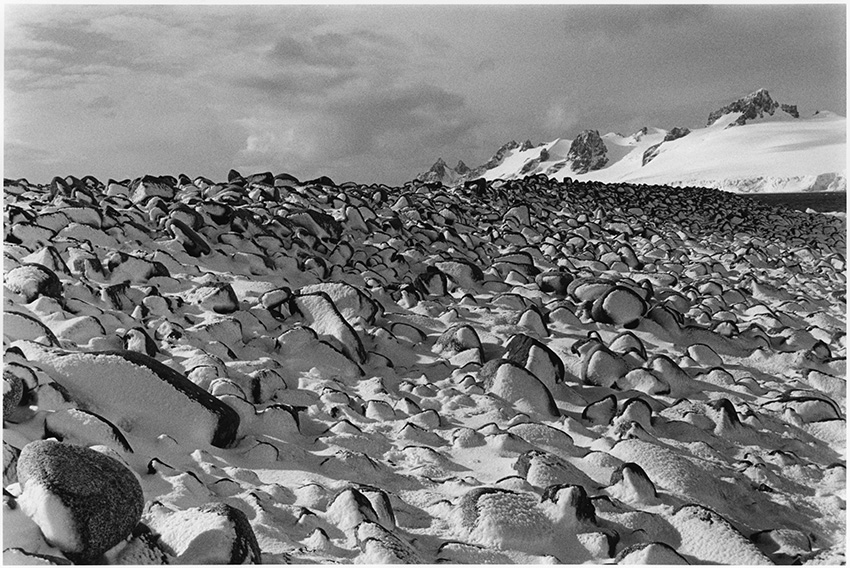

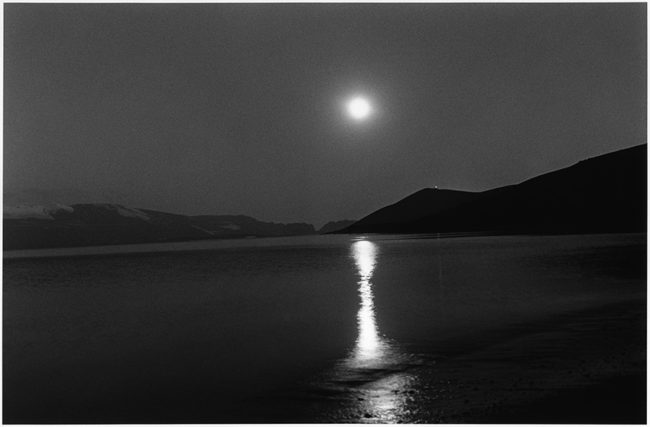

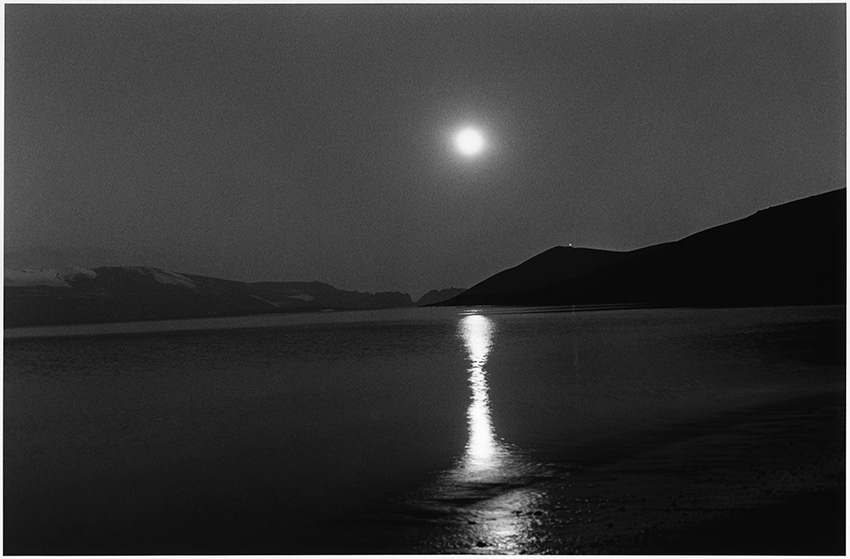

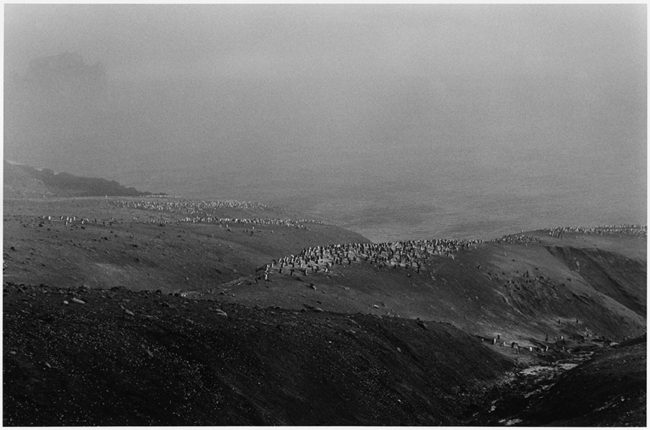

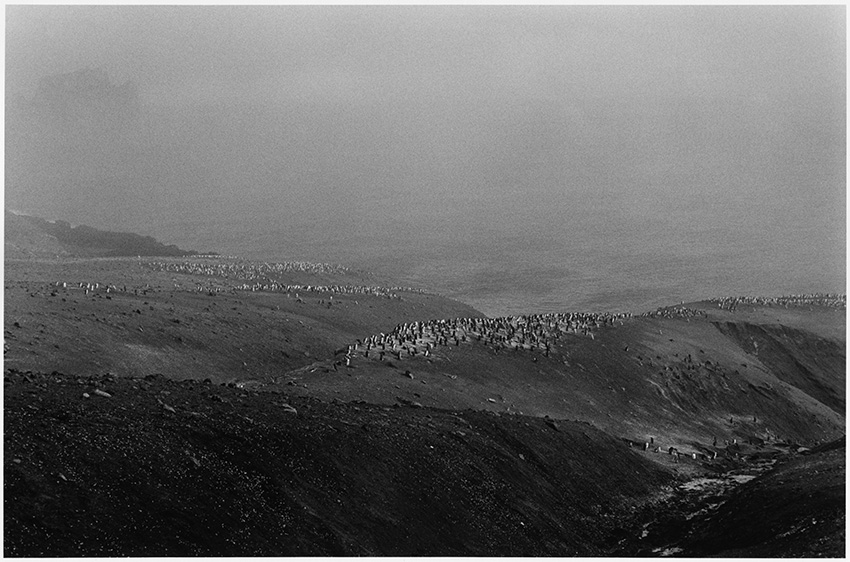

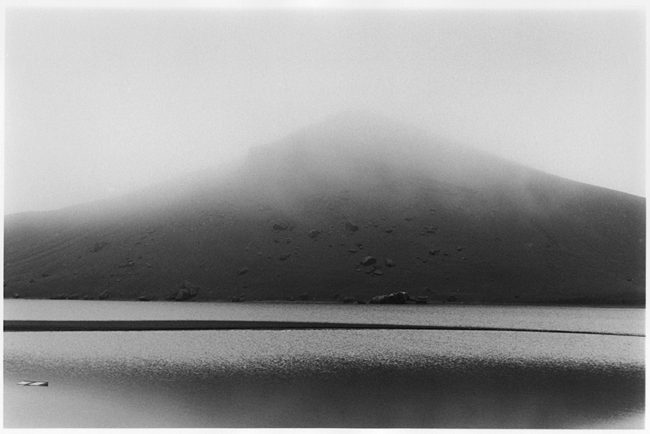

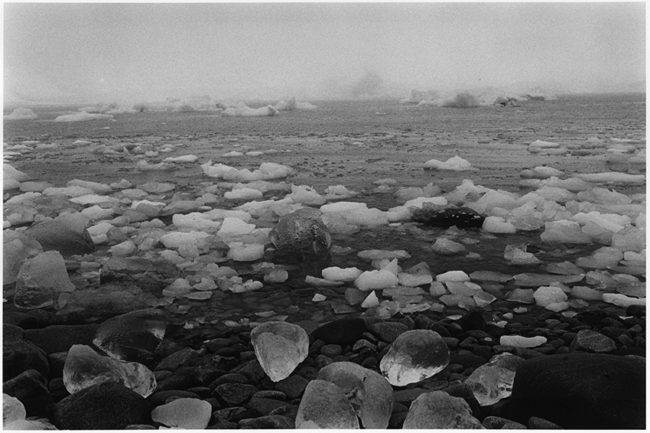

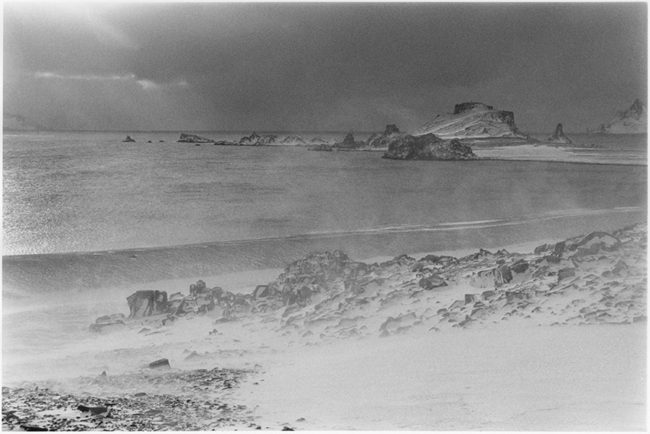

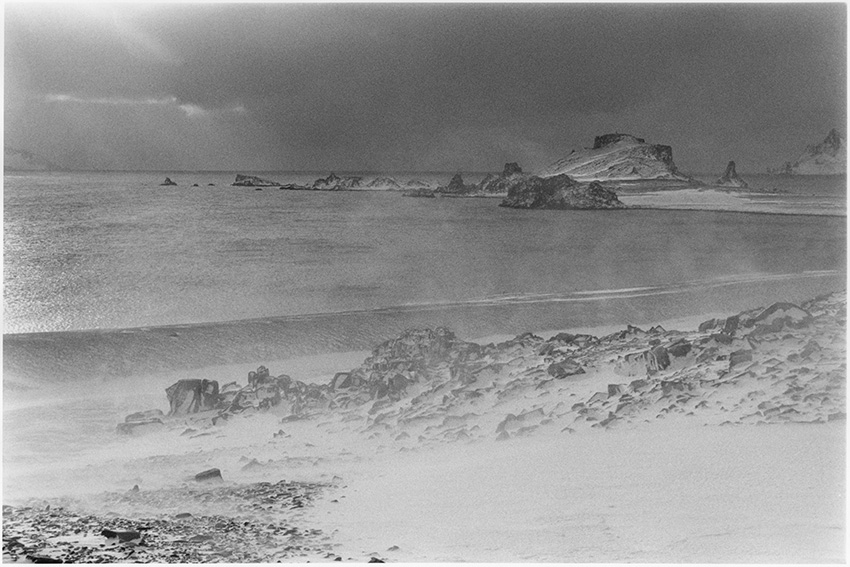

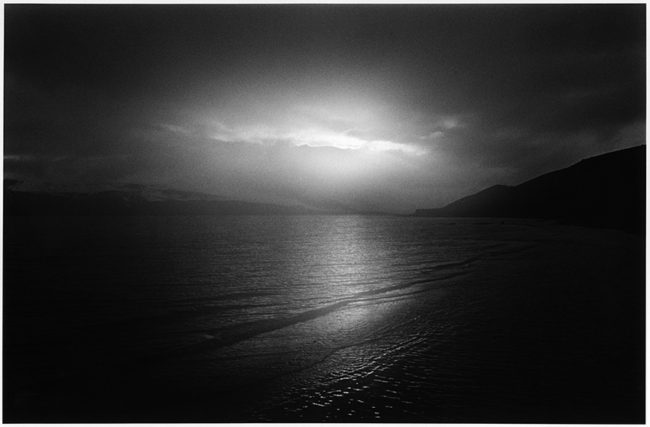

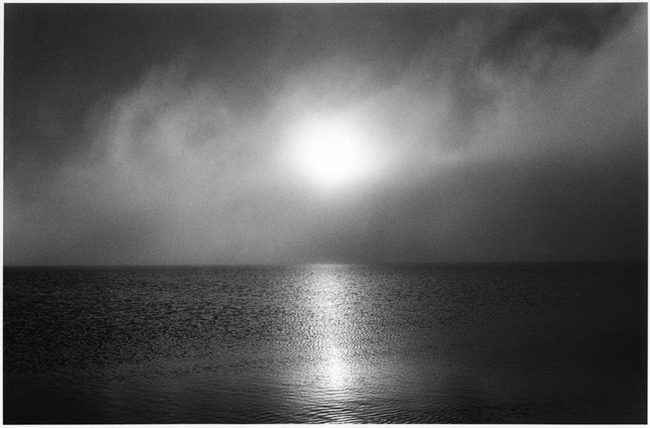

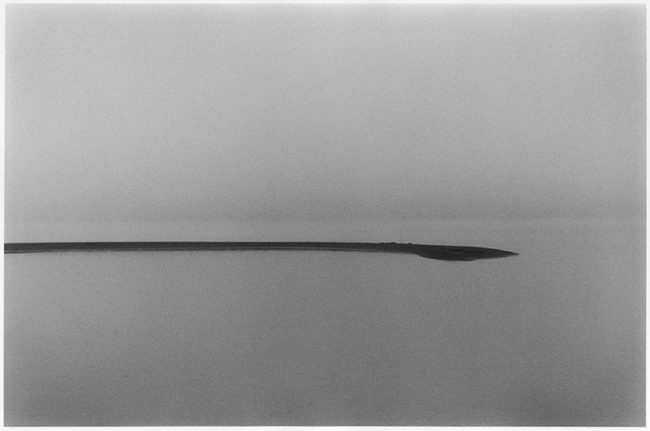

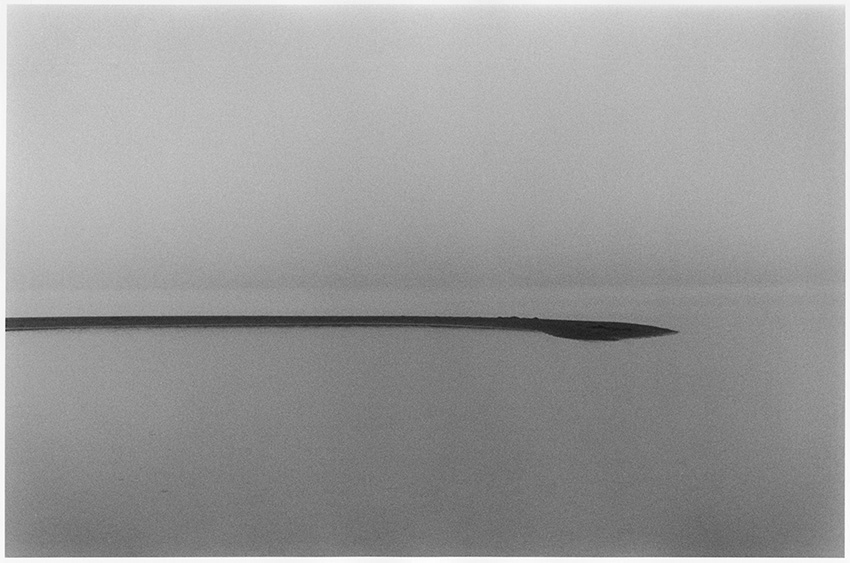

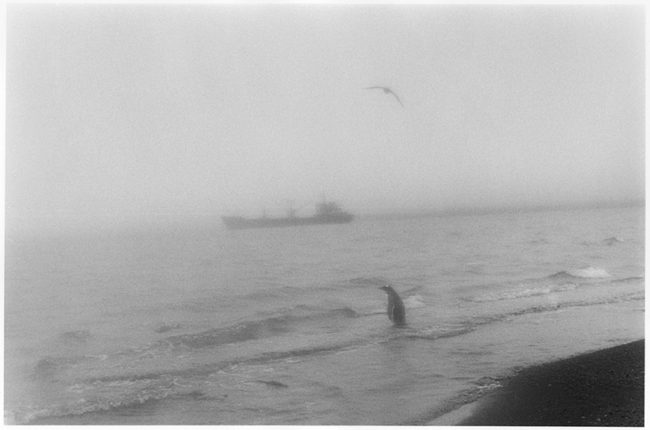

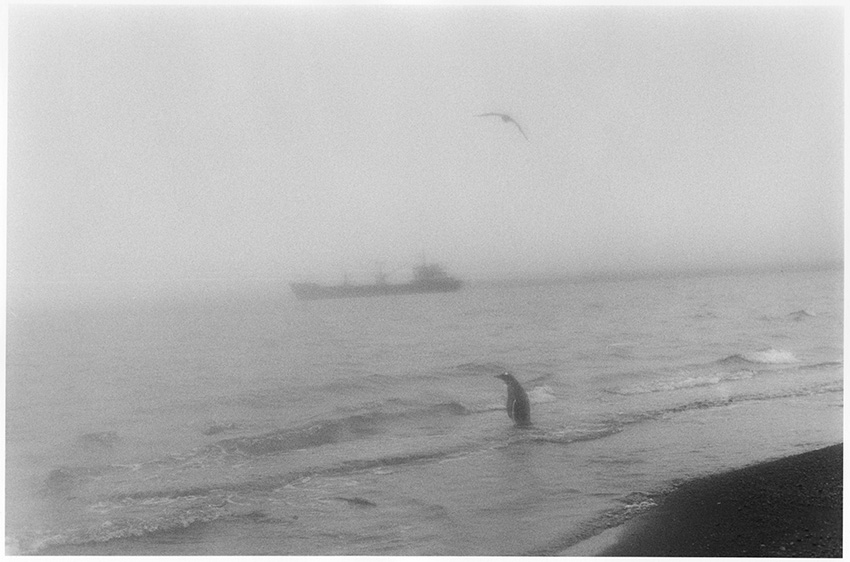

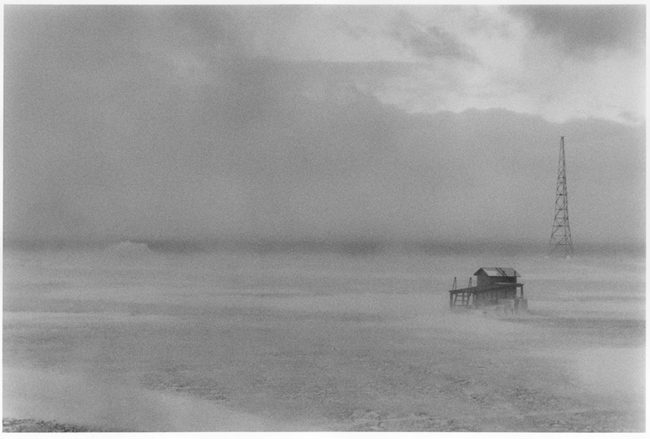

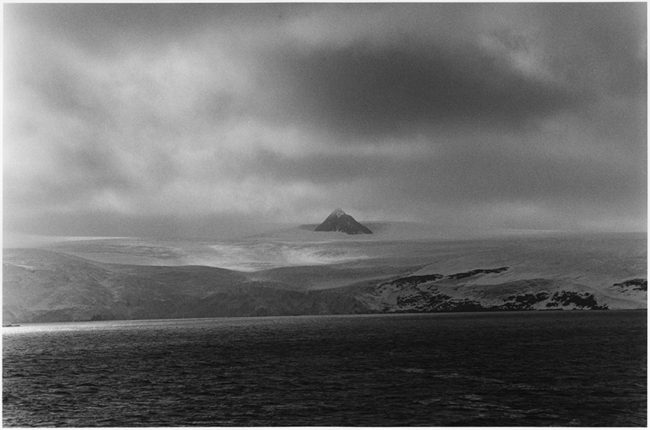

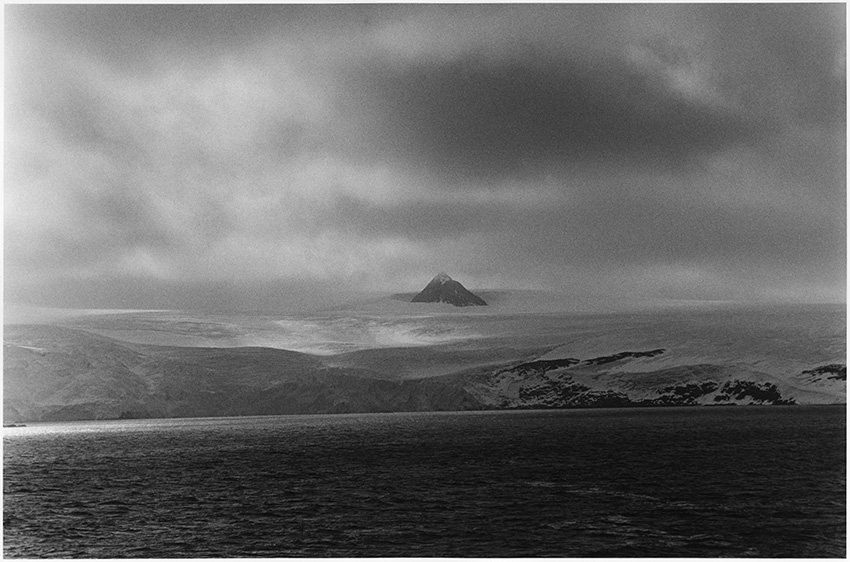

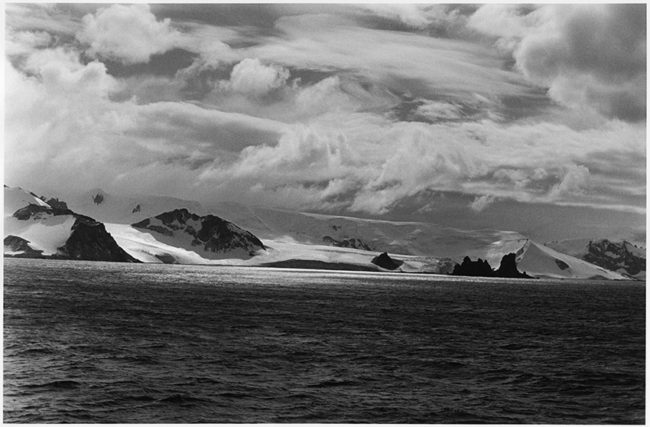

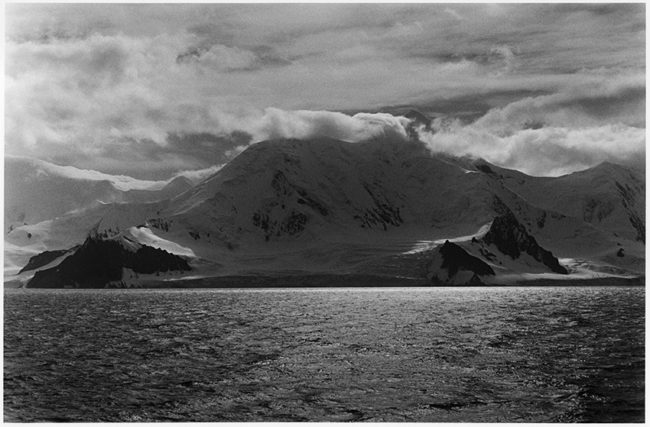

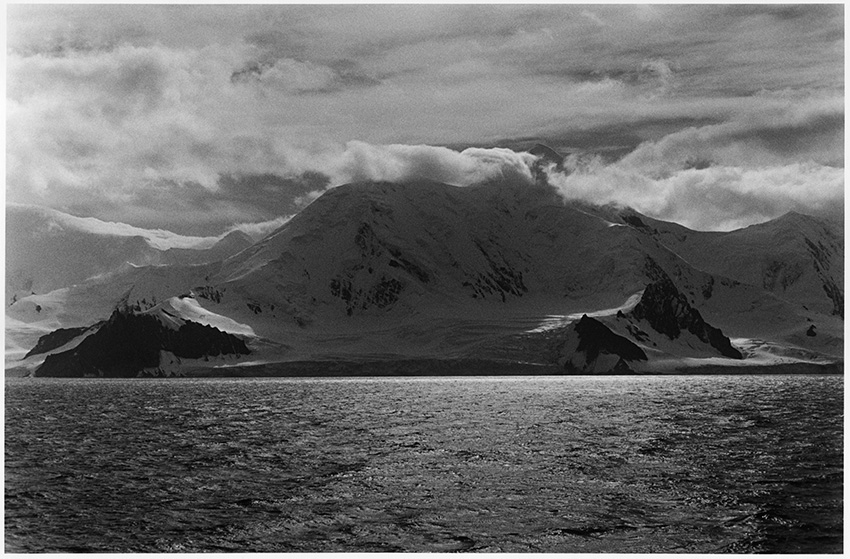

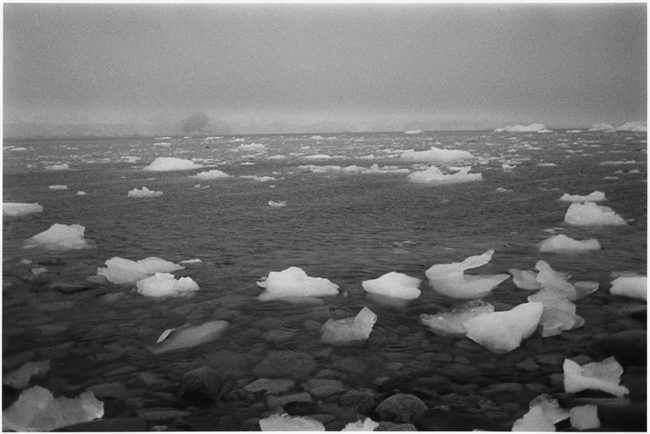

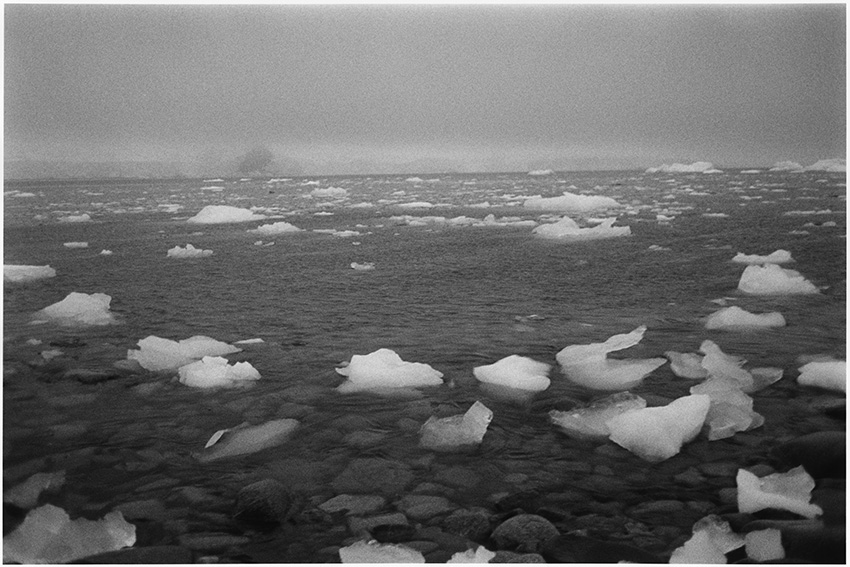

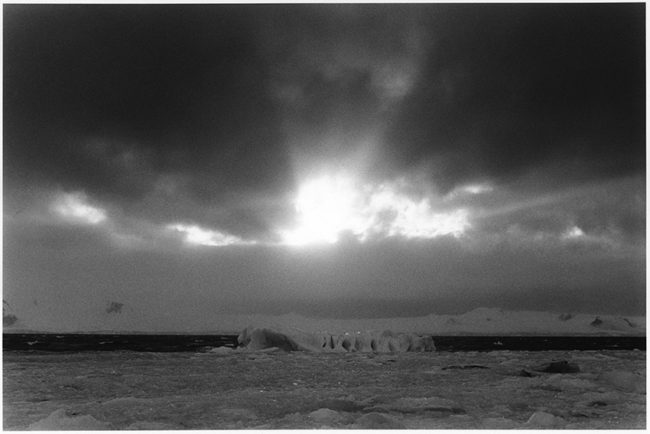

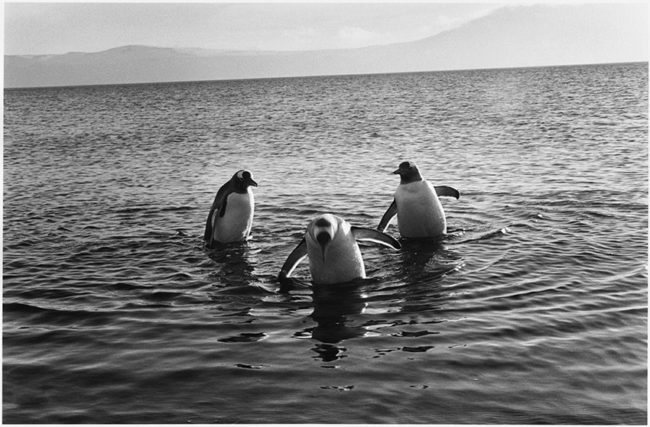

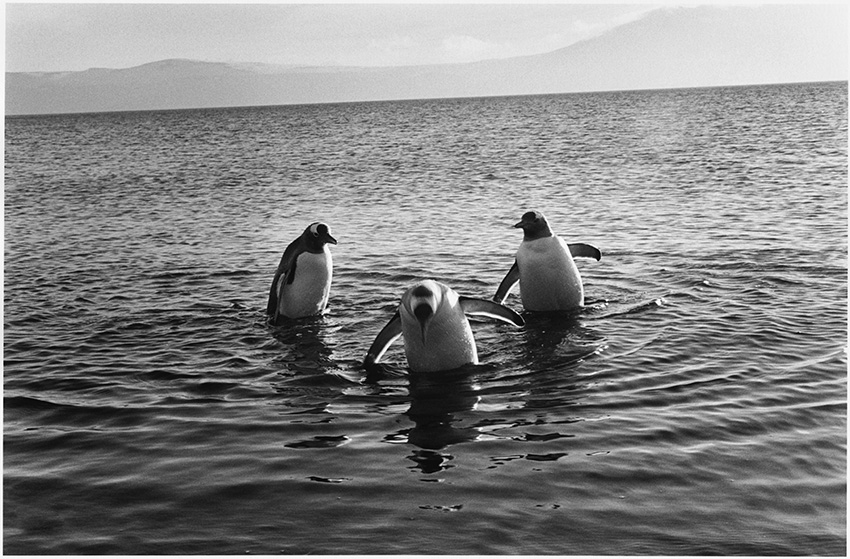

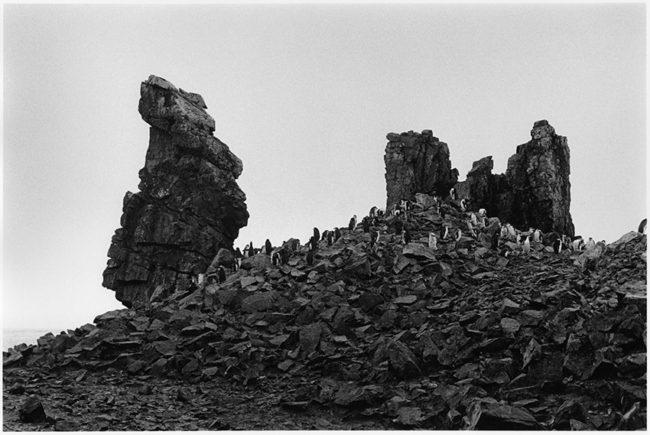

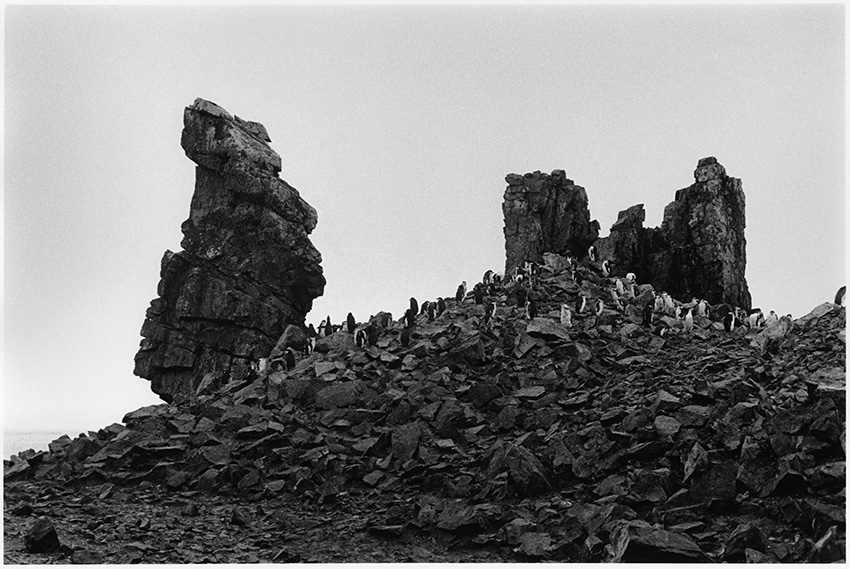

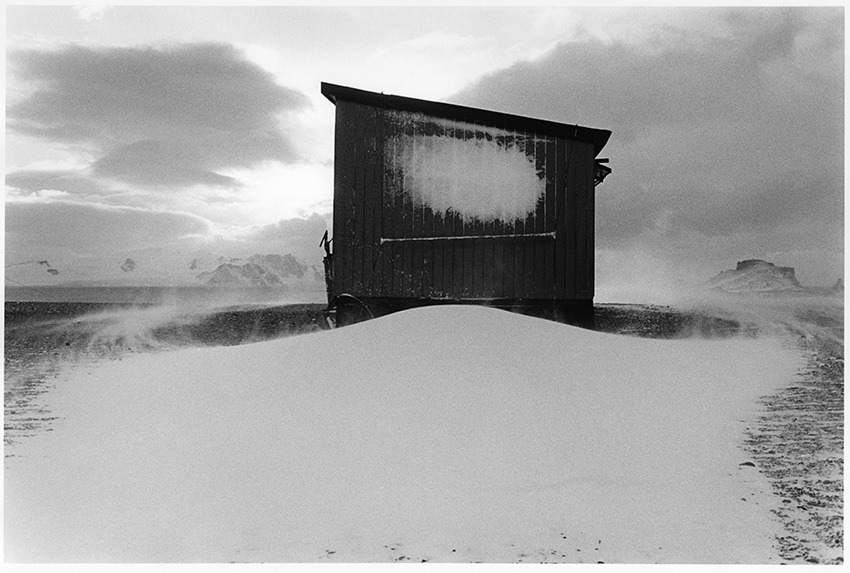

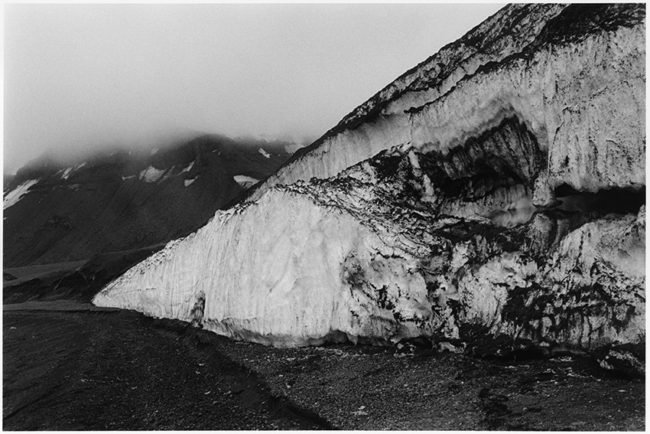

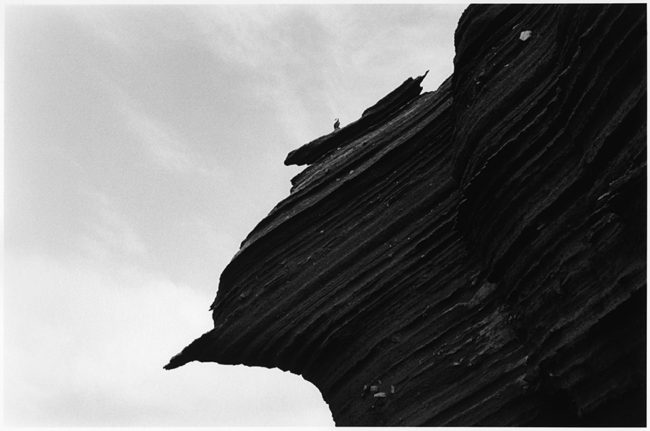

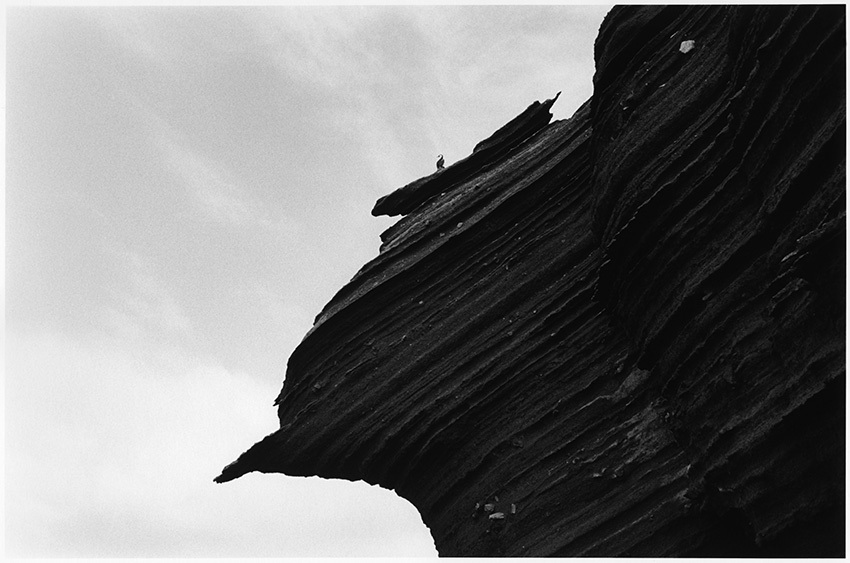

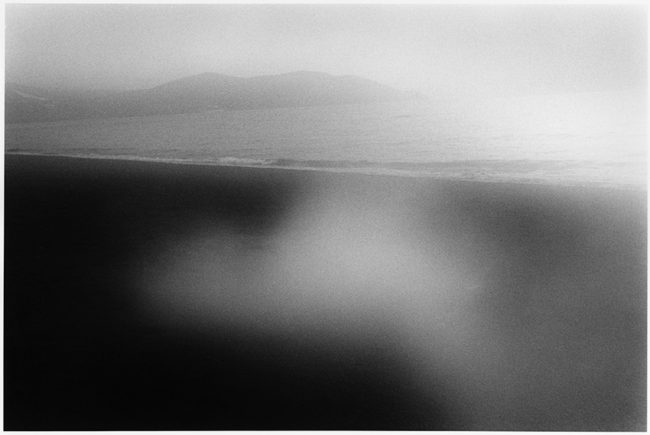

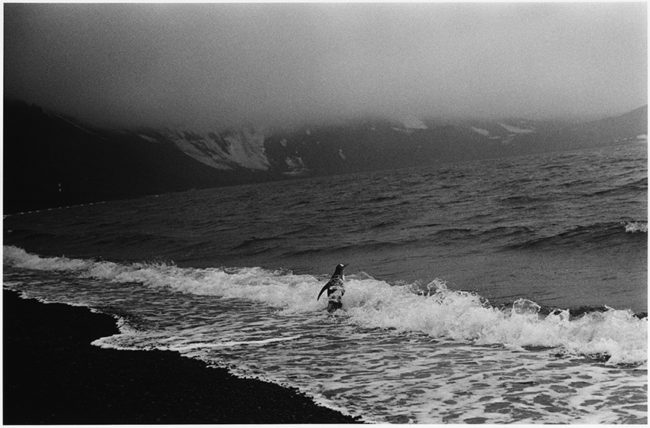

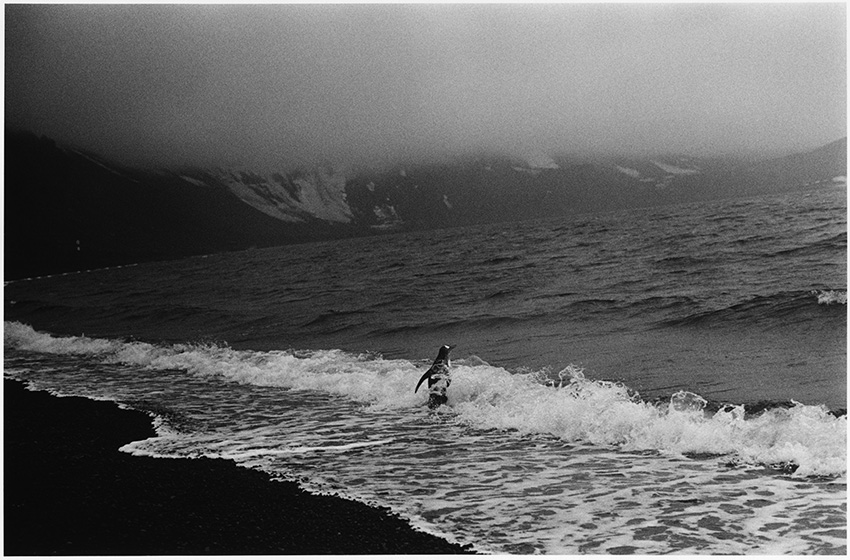

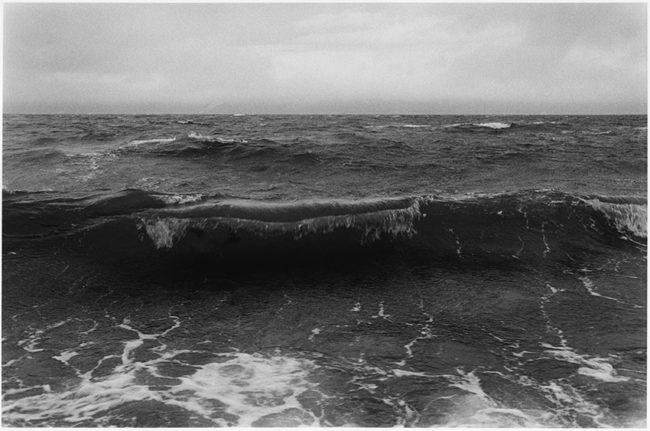

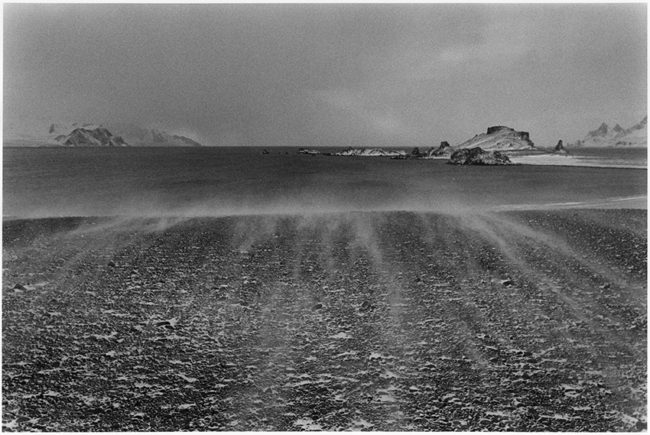

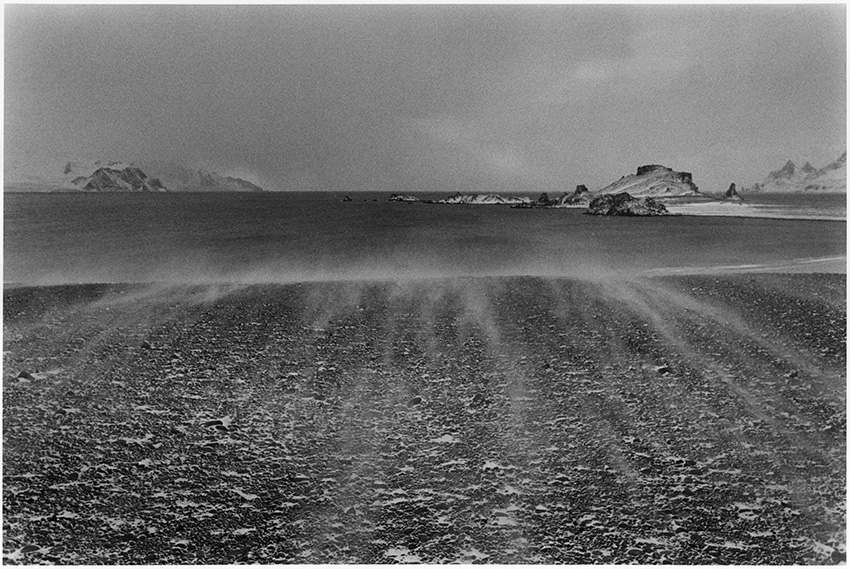

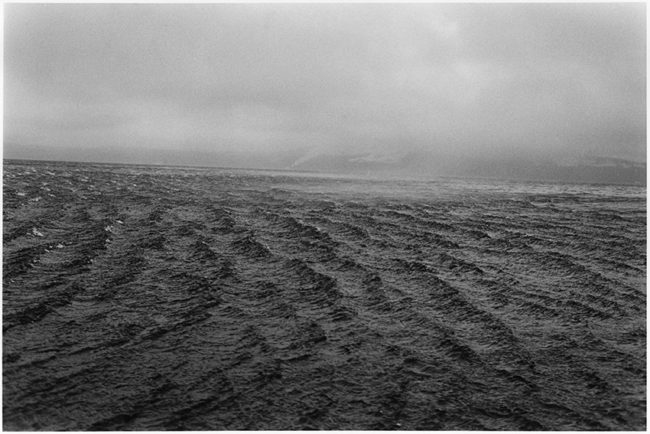

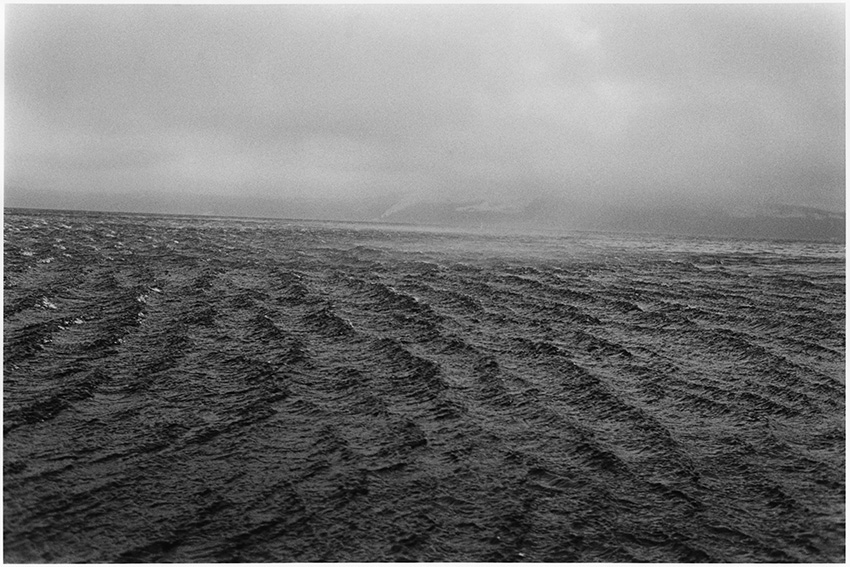

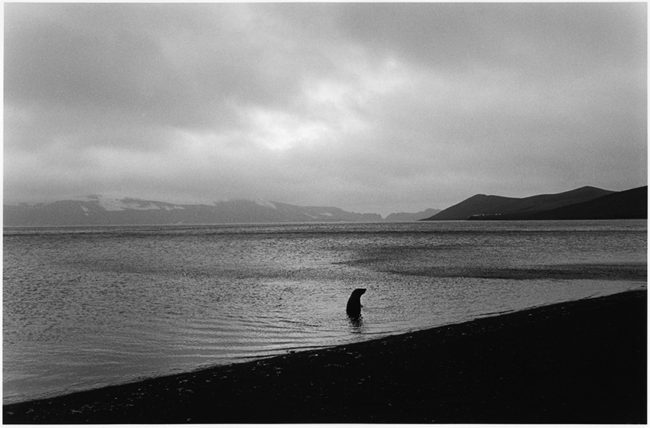

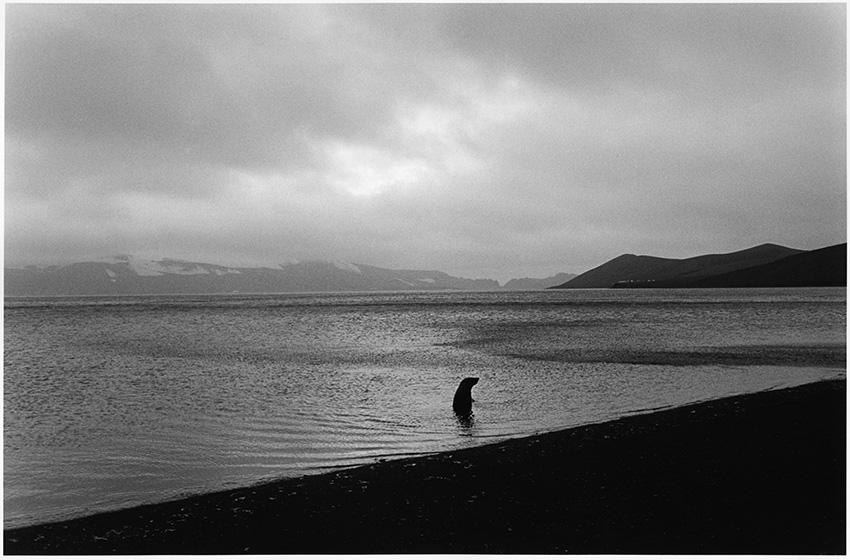

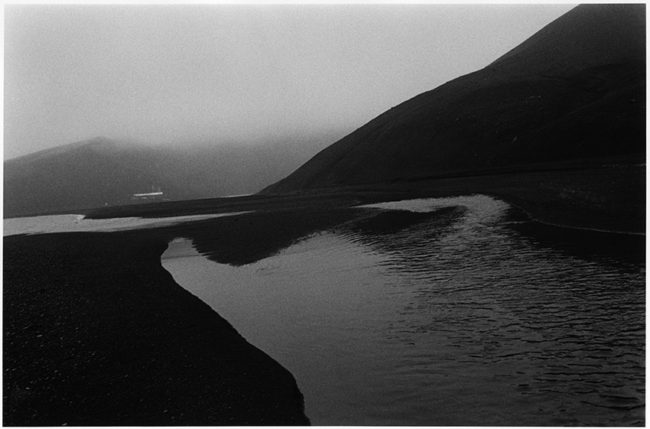

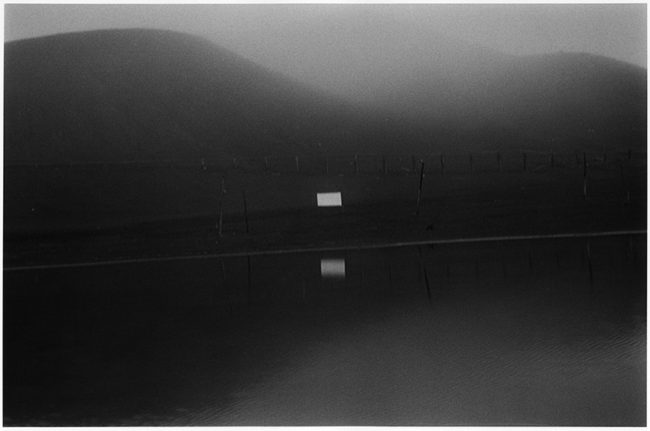

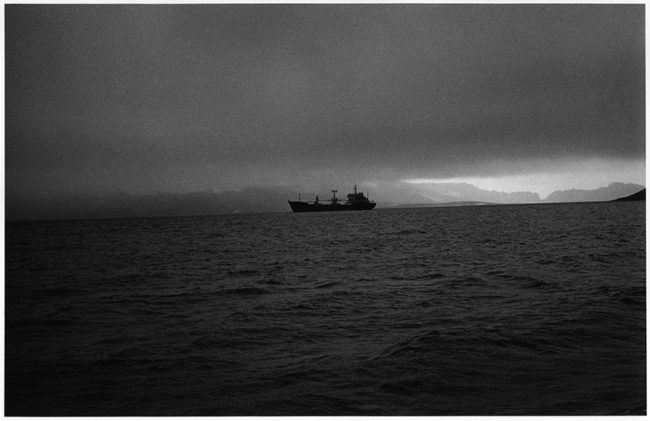

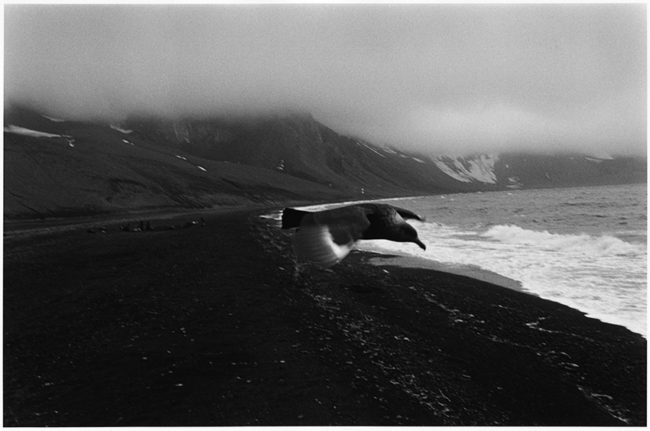

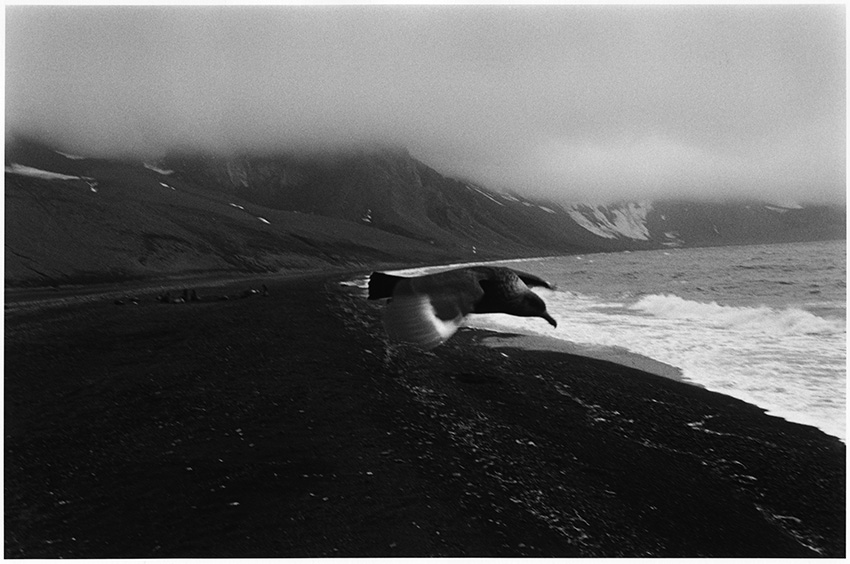

Adriana Lestido was born in Buenos Aires, in 1955. She began her studies in photography in 1979 at the at the Avellaneda School of Audio-visual Arts. Between 1982 and 1995 she worked as a photojournalist for the newspaper La Voz, the Agency DyN and for the newspaper Página 12. Among numerous awards Lestido was the first Argentine photographer to receive the Guggenheim Grant -award (1995) and Hasselblad award(1991), and the Mother Jones award (1997). She received the prize to the trajectory (2021, National Academy of Fine Arts), Grand Acquisition Award of the National Photography Salon (2009), Lifetime Achievement Award (Argentine Association of Art Critics, 2009) and Outstanding Personality of Culture by the Legislature of CABA (2010), among others. She also was awarded with the Konex Award in 2002 and received the Konex Platino in 2022. She has made the photo-essays Antártida (Antarctic, 2012), México (2010), El amor (Love, 1992-2005), Madres e hijas (Mothers and daughters, 1995-1998), Mujeres Presas (Imprisoned women, 1991-1993), Madres Adolescentes (Adolescent mothers, 1988-1990) and Hospital Infanto Juvenil (Children ́s hospital, 1986-1988) & Metrópolis (1988-1999) . She is the author of eight books. Her latest publication, Metrópolis (Ediciones Larivère / RM, Madrid, 2021), was selected as the best book at PhotoEspaña 2022 and for the Prix du Livre Arles 2022. She also published Antártida negra (Capital Intelectual, 2017), Antártida negra. The diaries (Tusquets, 2017), Lo Que Se Ve, Fotografías 1992/2005 (What Can Be Seen 1992/2005, published by Capital Intelectual, 2012), La Obra (The Work by Capital Intelectual, 2011), Interior (Capital Intelectual, 2010), Mothers and daughters (La Azotea Editorial, 2003, with the support of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation) and Mujeres presas (Imprisoned Women, Argentine Photographers Collection, 1st edition 2001, 2nd edition 2008).

Her most recent individual exhibitions include Lo Que Se Ve (What Can Be Seen), exhibited for the first time in 2008 in the Cronopios hall at the Centro Cultural Recoleta (Buenos Aires); Amores dificiles (Difficult Loves), in 2010, at Casa de America, Madrid, an official exhibition by PhotoEspaña 2010; Adriana Lestido. Fotografias 1979/2007 (Adriana Lestido. Photographs 1979/2007), exhibited between may and july of 2013 at the National Museum of Fine Arts, Argentina; o Que Se Ve (What Can Be Seen) exhibited in 2014 at Art Gallery, Consulate General of Argentina, New York, USA; and at the Museum Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa; additionally, in 2015 it was exhibited at the Museo Caraffa (Córdoba, Argentina) and at the Museo Nacional de Belas Artes (MNBA), Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. In 2015 she also exhibited the photo-essay Mexico at Rolf Art (Buenos Aires). In 2016 she exhibited Algunas chicas (Some girls) at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Buenos Aires (MACBA); Was zu sehen ist (What Can Be Seen) at the HAUS am KLEISPARK, Berlin. In 2017/2018, in the commemoration of the 20 years of PHE (PhotoEspaña), she exhibited Ellas, Nosotras, Vosotras (Them, us and you) at the Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo, Convento de la Merced, Ciudad Real, and at the Museo de Guadalajara, Guadalajara. She also exhibited La maldita primavera (Damned spring) at Rolf Art and at the Museo Dionisi, Cordoba. In 2019 she exhibited Algunas chicas (Some girls) at the documentary photography festival Image Singulères, Séte, France. Her series Antártida negra was exhibited for the first time at the Fortabat Foundation, between October 2017 and February 2018, then at the gallery of the Argentine Embassy in Berlin, Germany, in 2019; in 2020 at Casa de América, Madrid, shows PHE20 official. She lives and works in Buenos Aires.

Her work make part of national and international Institutional & private collections, such as the MNBA – National Museum of Fine Arts from Buenos Aires, MAM – Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires; MALBA – Museum of Latin American Art from Buenos Aires; MFAH – Museum of Fine Arts (Houston, USA); Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris, France), Chateau d’eau (Toulouse, Francia), Hasselblad Center (Göteborg, Sweden), among others.

Adriana Lestido inició sus estuido en fotografía en 1979, en la Escuela de Arte y Técnicas Audiovisuales de Avellaneda. Entre 1982 y 1995 trabajó como fotoperiodista para el diario La Voz, la Agencia Diarios y Noticias (DyN) y el diario Página 12. Fue la primera fotógrafa argentina en recibir las becas Guggenheim (1995) y Hasselblad (1991), y el Premio Mother Jones (1997). Fue Premio a la Trayectoria (2021, Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes), Gran Premio Adquisición del Salón Nacional de Fotografía (2009), Premio a la Trayectoria (Asociación Argentina de Críticos de Arte, 2009) y Personalidad Destacada de la Cultura por la Legislatura de CABA (2010), entre otros. Fue galardonada con los Premio Konex en 2002, y Konex Platino en 2022. Ha realizado los ensayos Antártida (2012), México (2010), El amor (1992-2005), Madres e hijas (1995/98), Mujeres presas (1991/93), Madres adolescentes (1988-90) y Hospital Infanto-Juvenil (1986-88). Es autora de ocho libros. Su último libro, Metrópolis (Ediciones Larivère/RM, Madrid, 2021), fue seleccionado como mejor libro de PhotoEspaña 2022 y para el Prix du Livre Arles 2022. Publicó además Antártida negra (Capital Intelectual, 2017), Antártida negra. Los diarios (Tusquets, 2017), Lo Que Se Ve, Fotografías 1992/2005 (Capital Intelectual, 2012), La Obra (Capital Intelectual, 2011), Interior (Capital Intelectual, 2010), Madres e hijas (La Azotea Editorial, 2003, con el apoyo de John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation) y Mujeres presas (Colección Fotógrafos Argentinos, 1 ̊ edición 2001, 2o edición 2008).

Entre sus últimas exposiciones individuales se destaca la retrospectiva Lo Que Se Ve, exhibida por primera vez en 2008 en la sala Cronopios del Centro Cultural Recoleta (Buenos Aires); Amores Difíciles, en 2010, en Casa de América, Madrid, exposición oficial de PhotoEspaña 2010; Adriana Lestido. Fotografías 1979/2007, exhibida entre mayo y julio de 2013 en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Argentina; Lo Que Se Ve, exhibida en 2014 en Art Gallery, Consulado Argentino, New York, USA, en el Museum Africa, Johannesburgo, Sudáfrica; asimismo en el 2015 fue exhibida en el Museo Caraffa (Córdoba, Argentina) y en el Museo Nacional de Belas Artes (MNBA, Río de Janeiro, Brasil). En el 2015 también expuso la serie México en Rolf Art (Buenos Aires) el. En el 2016 expuso “Algunas chicas” en Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Buenos Aires (MACBA), Was zu sehen ist (Lo Que Se Ve) en el HAUS am KLEISPARK, Berlín. En el 2017/18, en conmemoración de los 20 años de PHE, expuso Ellas, Nosotras, Vosotras, en el Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo, Convento de la Merced, Ciudad Real, y Museo de Guadalajara, Guadalajara. También La maldita primavera en Rolf art y en el Museo Dionisi, Córdoba. En 2019 mostró Algunas chicas en ImageSingulières, Séte, Francia. Su serie Antártida negra fue exhibida por primera vez en la Fundación Fortabat, entre octubre de 2017 y febrero de 2018, luego en la galería de la Embajada argentina en Berlín, Alemania, en 2019, y en 2020 en Casa de América, Madrid, muestra oficial de PHE20. Vive y trabaja en Buenos Aires.

Su obra forma parte de colecciones institucionales y privadas nacionales e internacionales, como el MNBA – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires, MAM – Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires; MALBA – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires; MFAH – Museo de Bellas Artes (Houston, EE. UU.); Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain y Bibliothèque Nationale (París, Francia), Chateau d’eau (Toulouse, Francia), Hasselblad Centre (Göteborg, Suecia), entre otros.