No sólo los monumentos quedan en pie con los años. Así lo hacen también los desechos, las destrucciones, los desencuentros y los fracasos. Quizás sean éstos los que más perduren ya que sólo podrán dejar de serlo cuando pasen del olvido a ocupar un lugar en la historia.

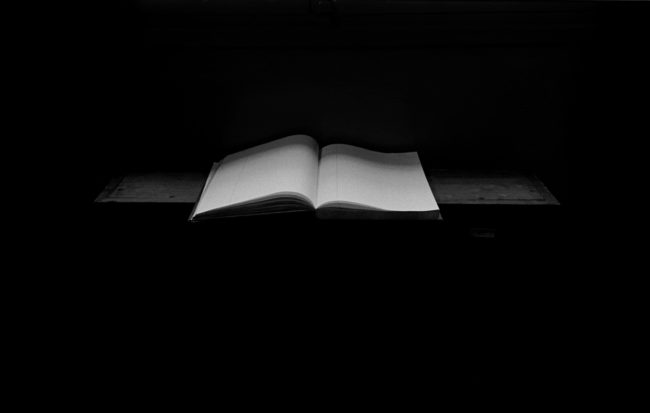

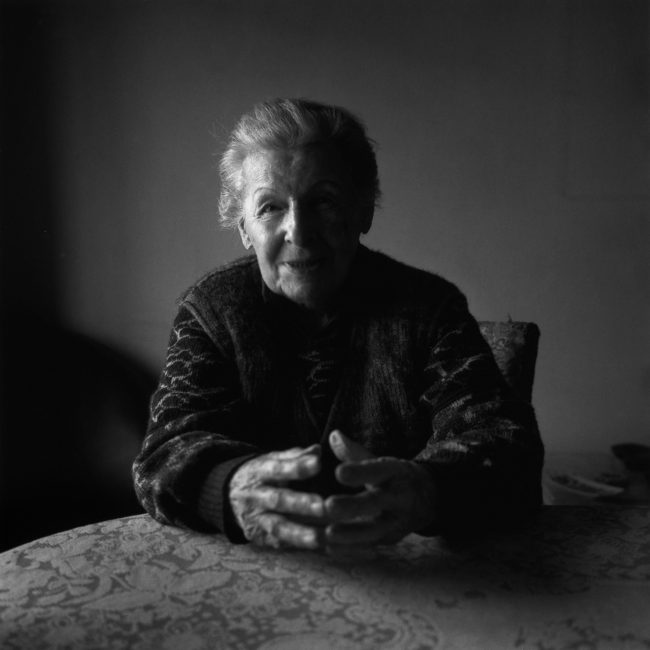

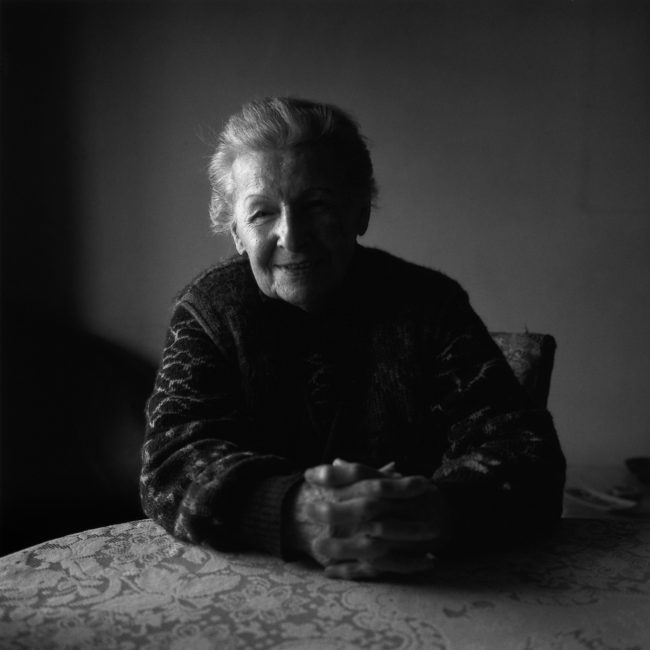

La fotografía de Santiago Porter es un ensayo sobre y con el tiempo. No pretende escribir una nueva historia pero sí explorar lo que está escrito en sus márgenes y que, por no haber sido monumentalizado, sigue latiendo por lo bajo. Porque evocar el pasado desde el presente es un desafío a nuestra manera de pensar quiénes somos, quiénes hemos sido y, por qué no, quiénes seremos. El tiempo deja una marca a cada paso y detrás de él, Porter construye su inventario.

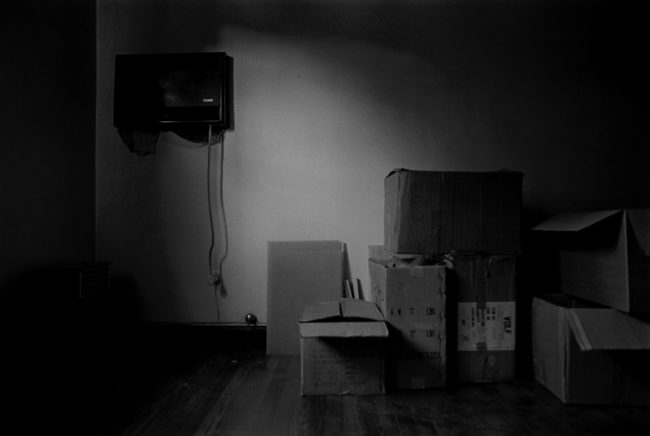

Pero no nos confundamos, si bien en un comienzo la fotografía le sirvió para burlar la fugaz existencia de las cosas, con el tiempo Santiago Porter se dio cuenta de que no existe tal fugacidad, sino que lo que ocurre es que el peso de la historia se imprime en cada rincón, habita en cada detalle, es más: que la historia se ve en lo detalles. Claro que, al igual que para los románticos de fines del siglo XVIII, esos detalles no se traducen en información, no están en la superficie sino que conforman la esencia de las cosas, eso que puede ser evocado y a la vez manifestarse con su mayor fuerza.

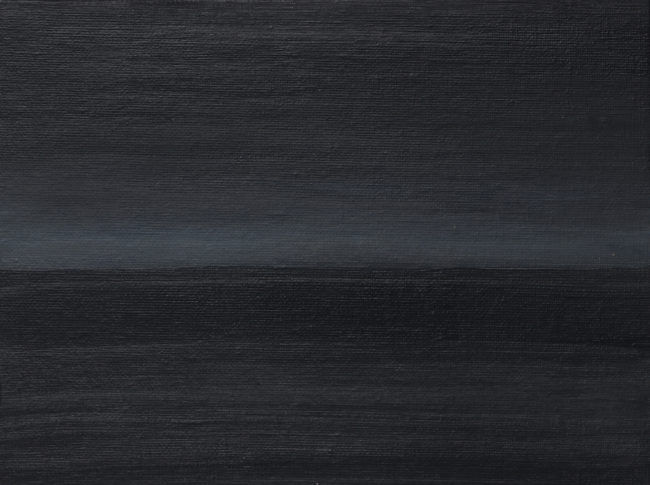

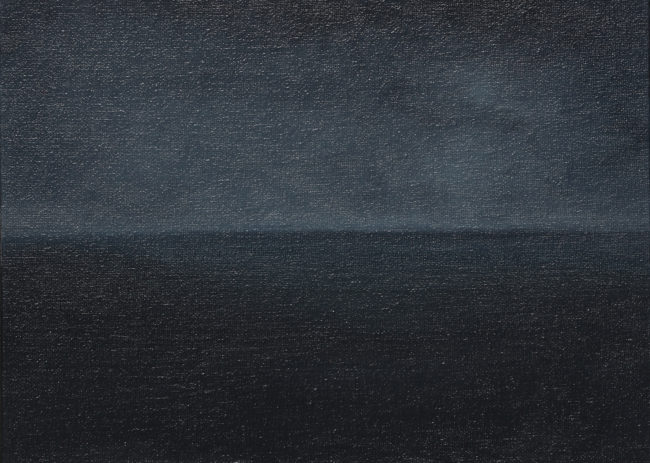

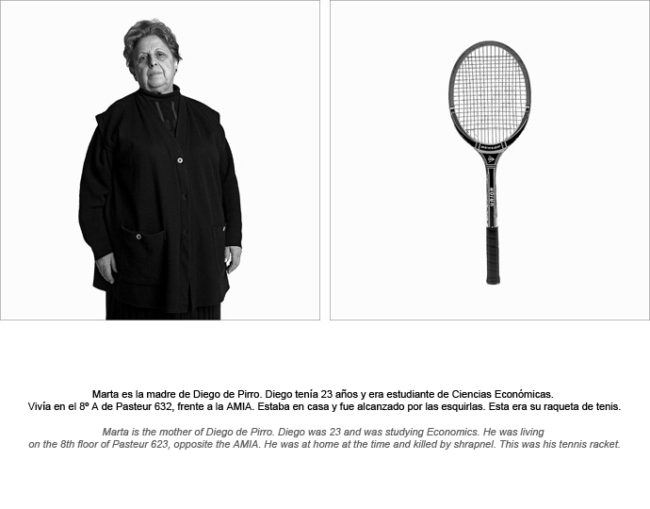

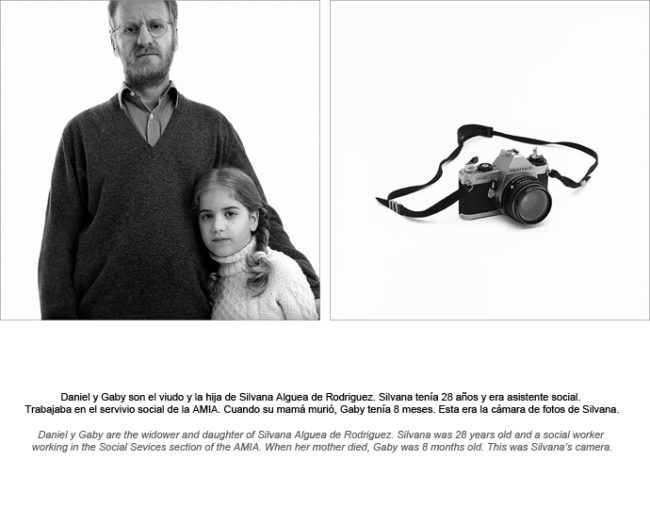

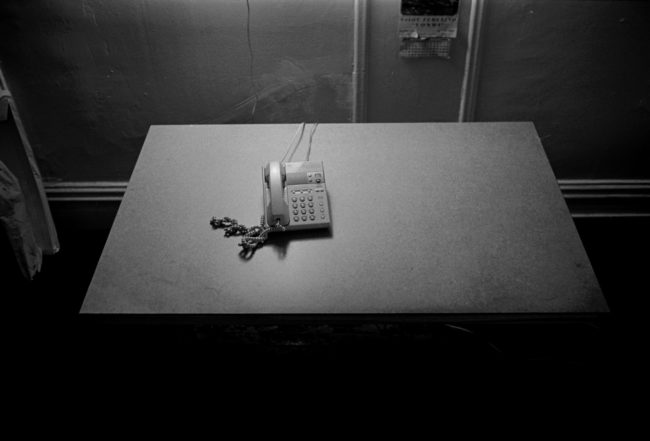

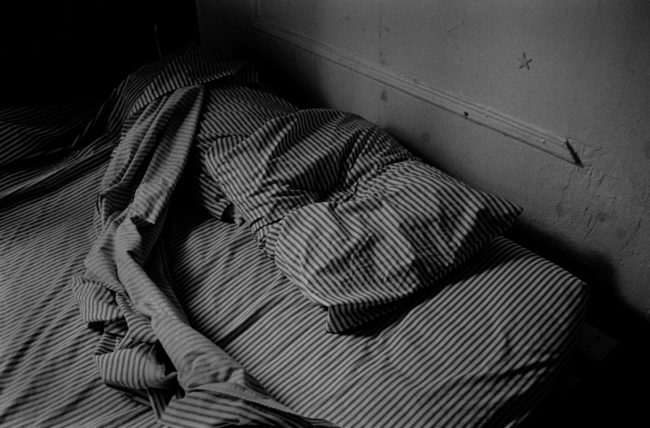

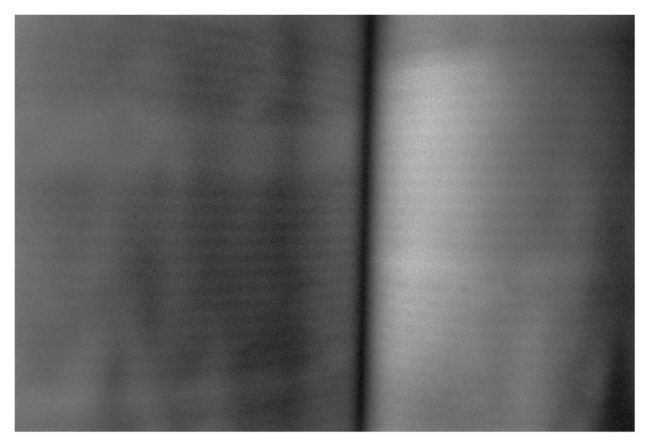

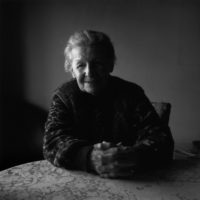

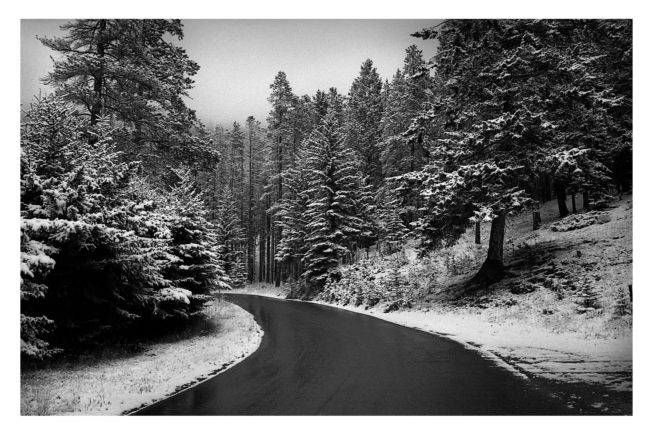

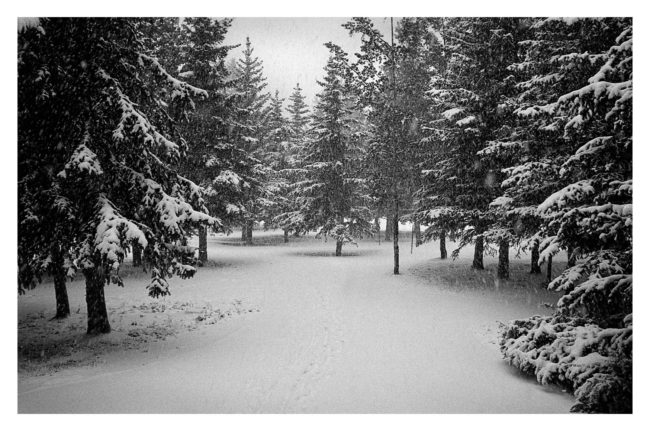

Así es que en los últimos años, Porter dirigió su trabajo tras la inquietud que le despierta la relación entre el aspecto de las cosas y su historia. Tanto como para Beckett el teatro, para él la fotografía es una necesidad más que una elección. No se trata de un ejercicio instantáneo en el que se registran imágenes sin mediación del tiempo: con paciencia contemplativa y concentración métrica, compone sus fotografías desplegando recursos que retengan nuestra atención y nos guíen hacia la idea o móvil que lo llevó a tomarlas. Sus fotografías no nos muestran las cosas como son, sino que exaltan el sentido que adquieren al ser fotografiadas, esa capacidad evocativa que poseen las metonimias y que para Porter significa el desafío de decir cada vez más con menos.

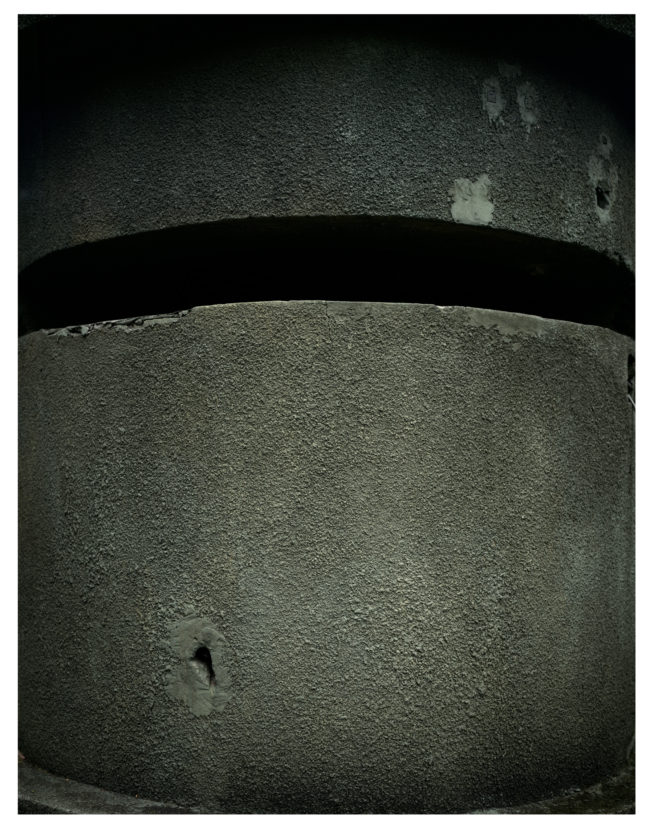

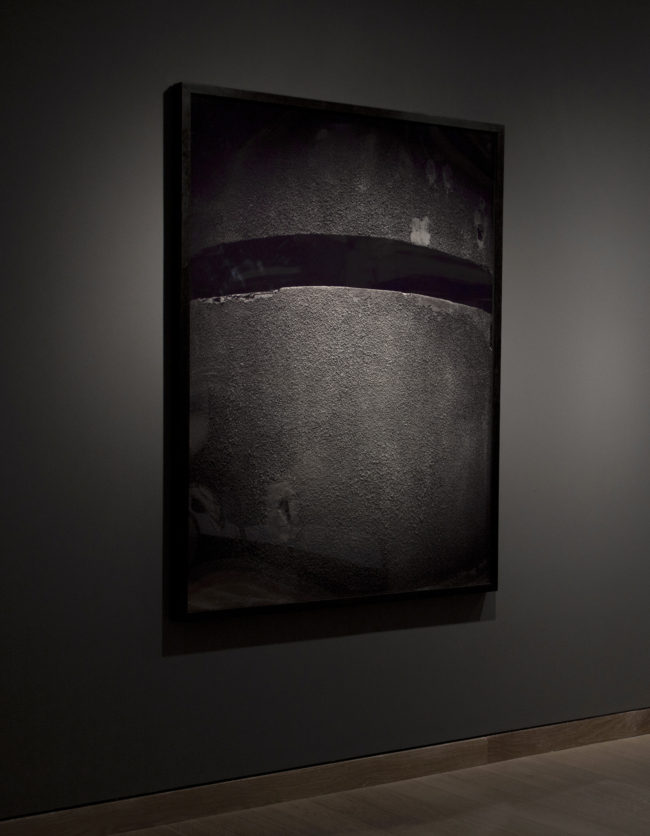

De técnica preciosista, encuadre frontal y gran tamaño, las fotografías parecen bastarse con tan solo un efecto denotativo, incluso los títulos de cada una de las obras se atienen a nominar cada imagen sin rodeos ni enigmas; sin embargo, una densidad poética y conceptual vibra a través de los marcos de cada imagen. “La imagen nunca es una realidad sencilla”: así Rancière introduce la idea de que las imágenes del arte establecen un vínculo entre lo decible y lo visible, un vínculo que no es directo sino que se encuentra mediado por tropos del discurso que, desafiando la simetría de las semejanzas, trazan un puente entre lo visible y lo invisible.

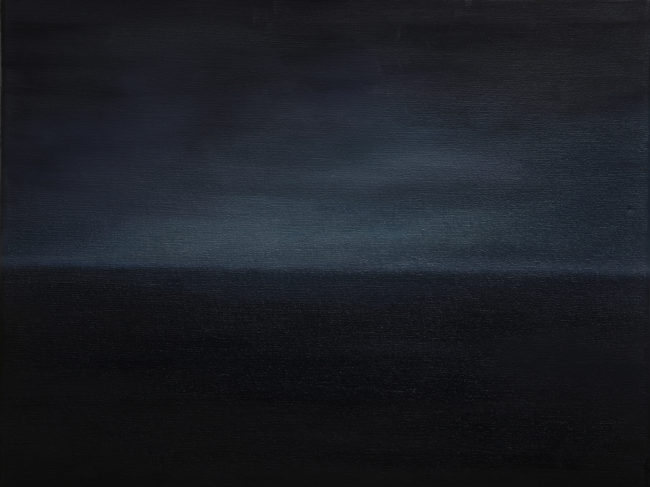

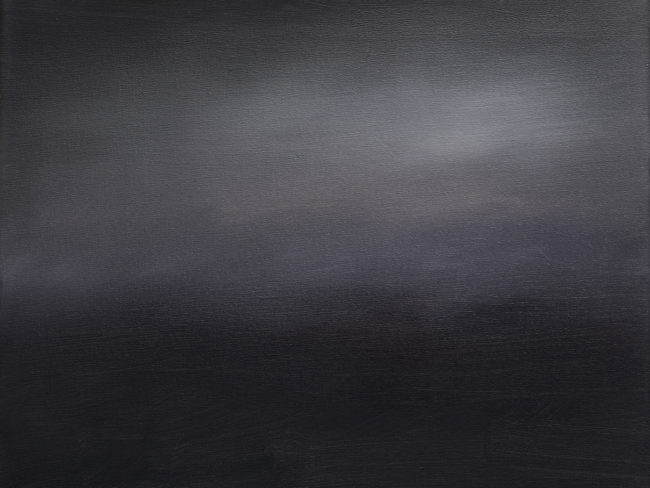

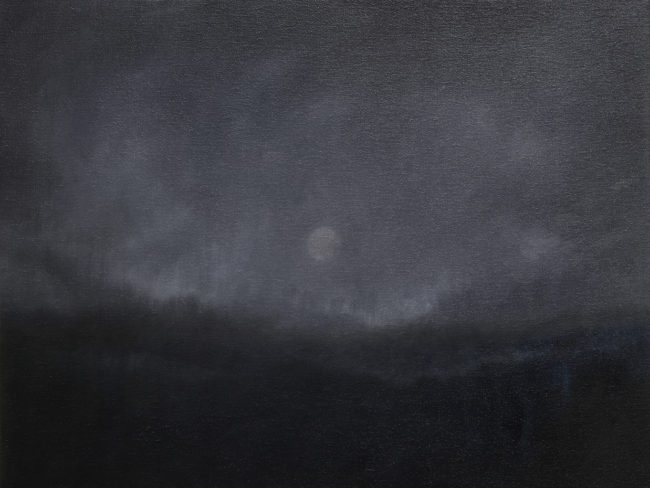

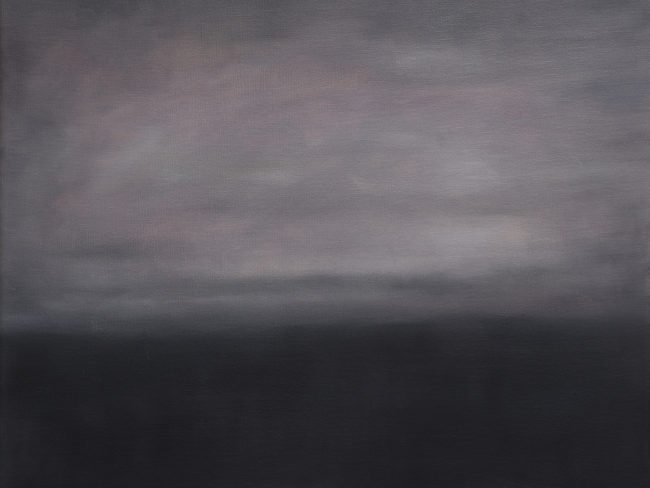

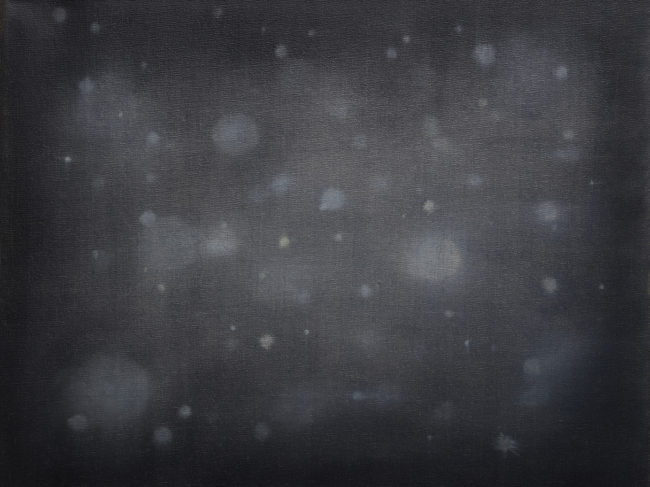

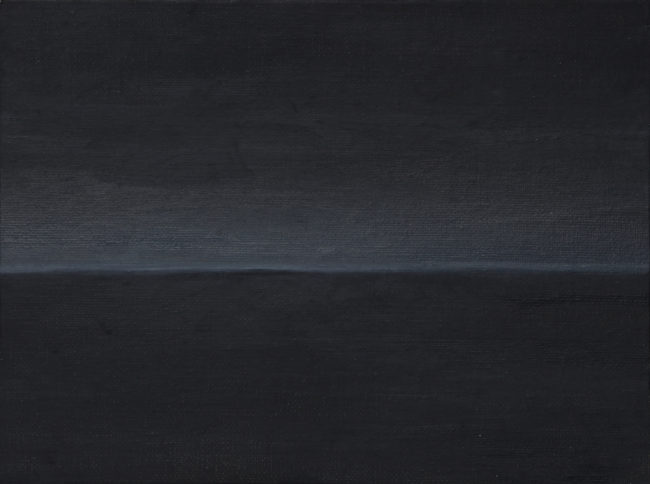

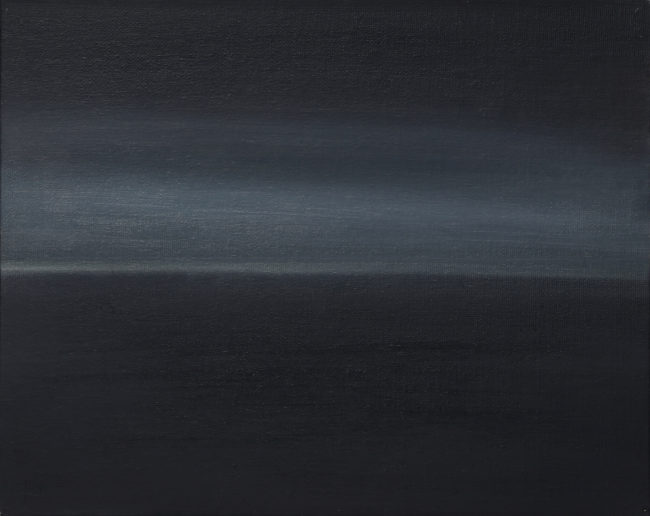

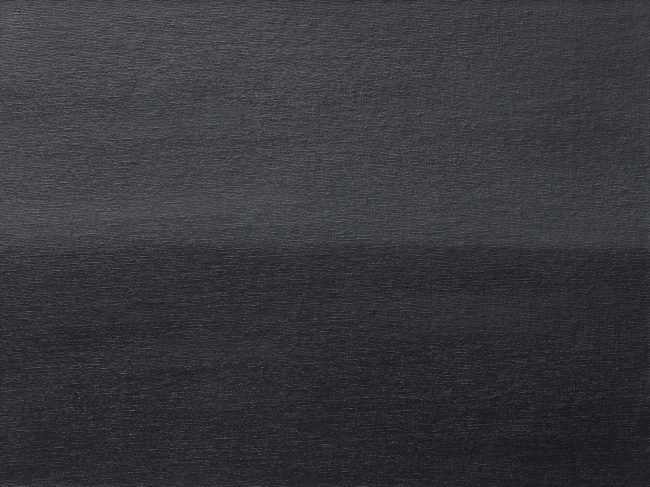

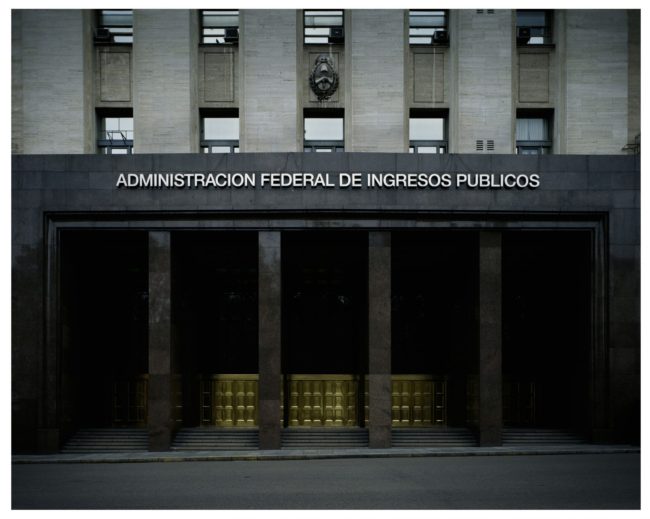

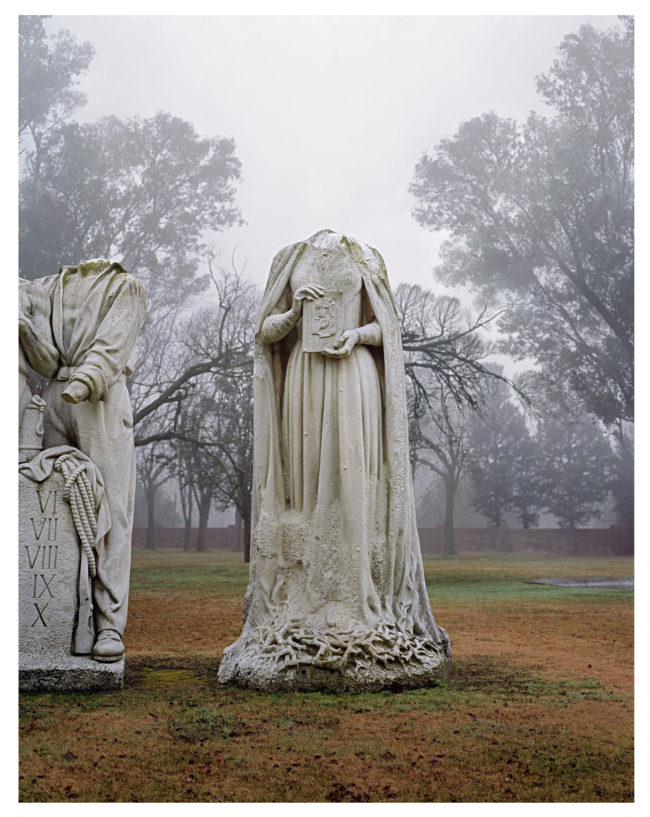

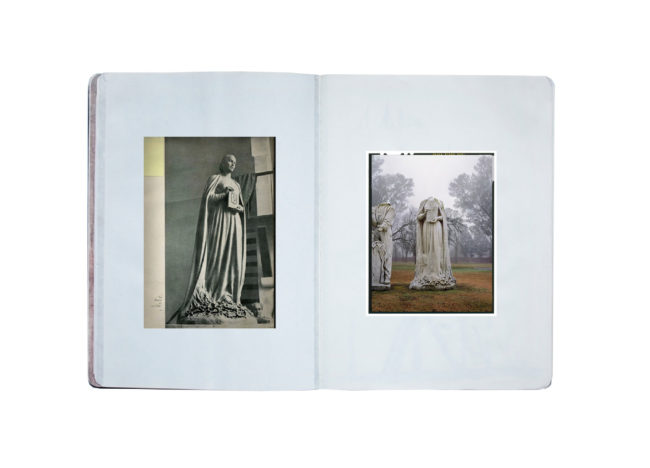

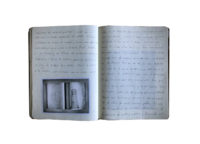

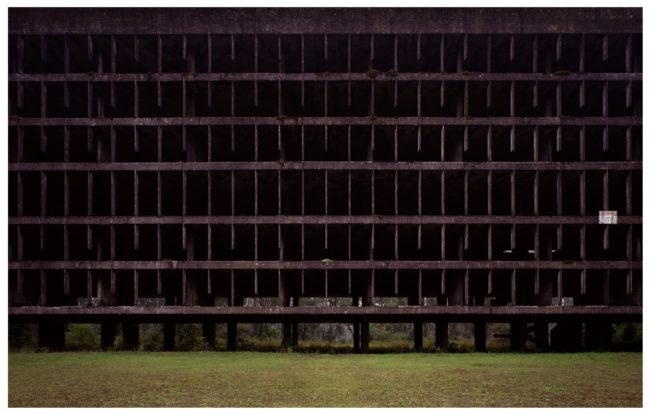

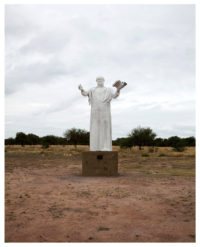

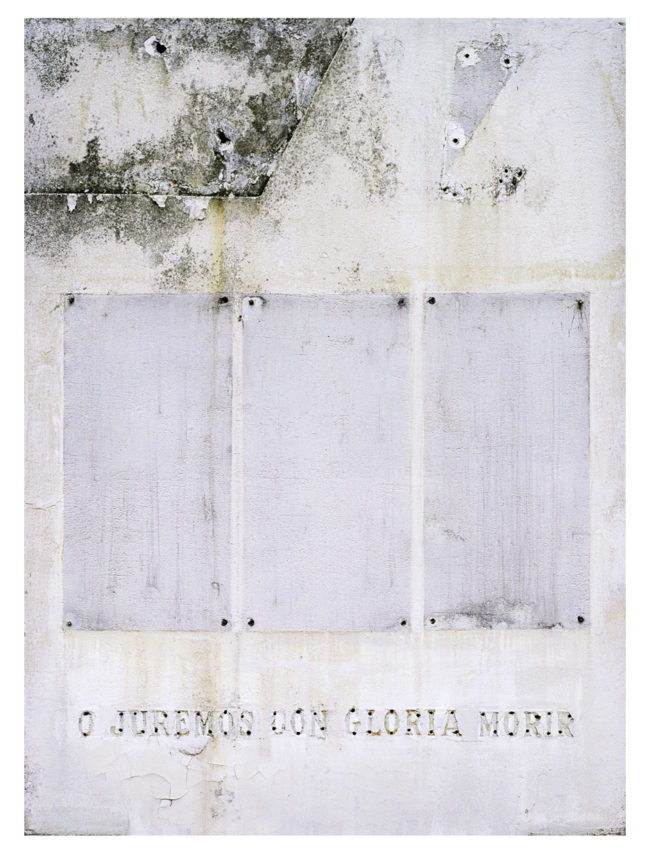

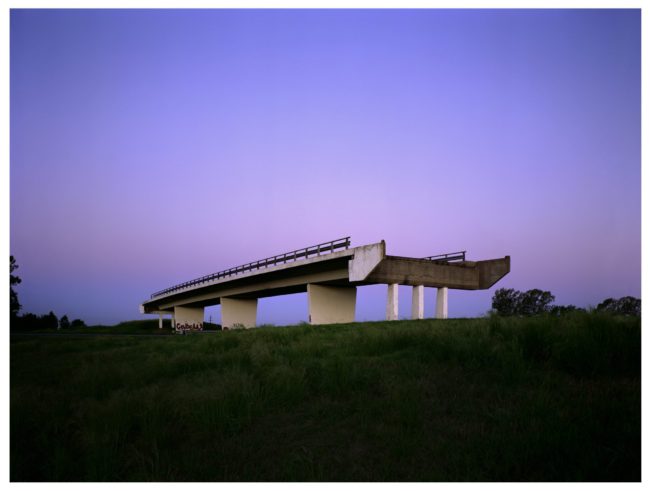

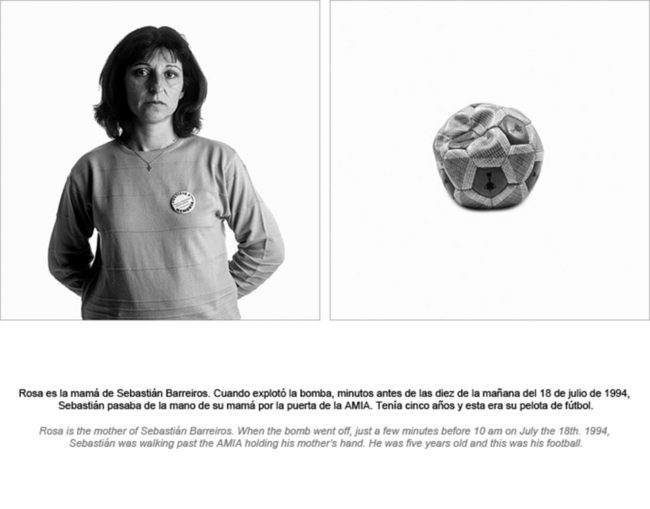

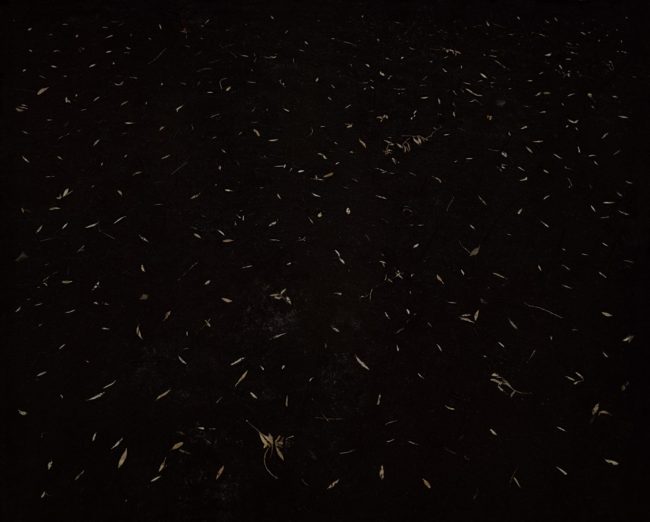

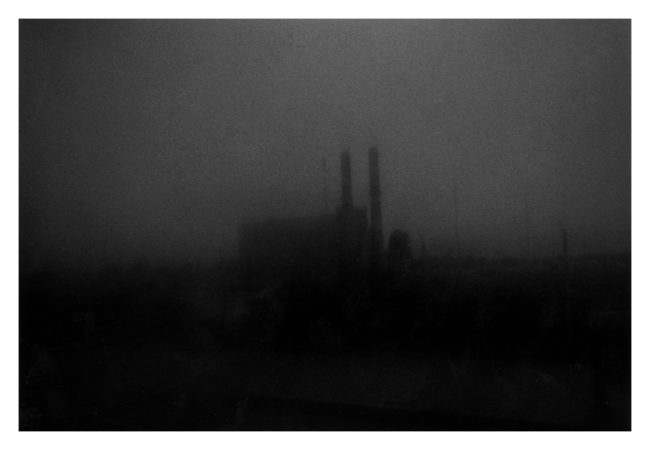

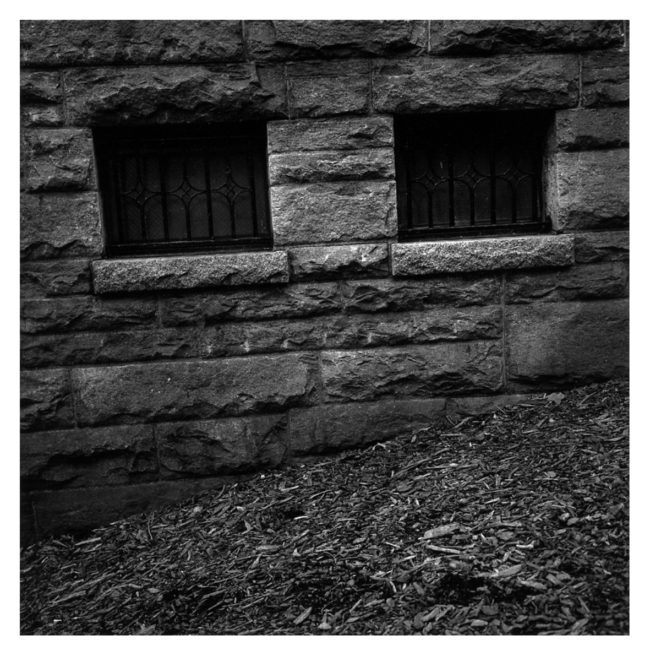

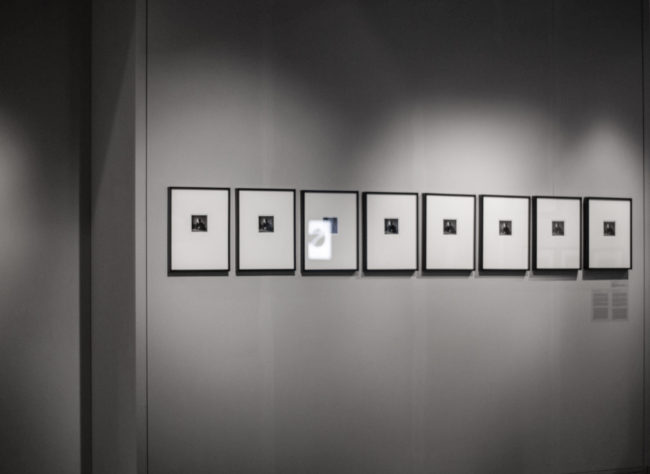

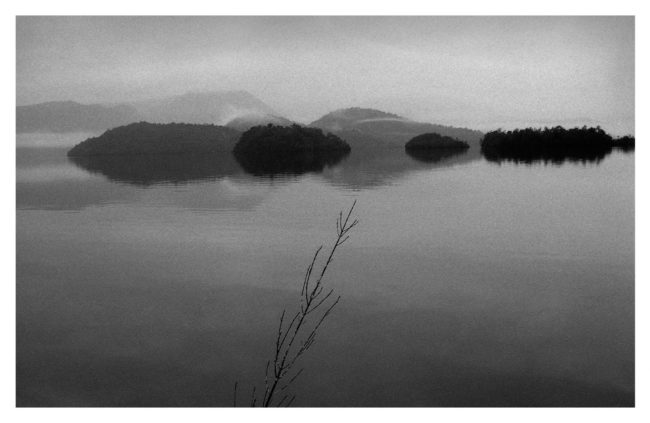

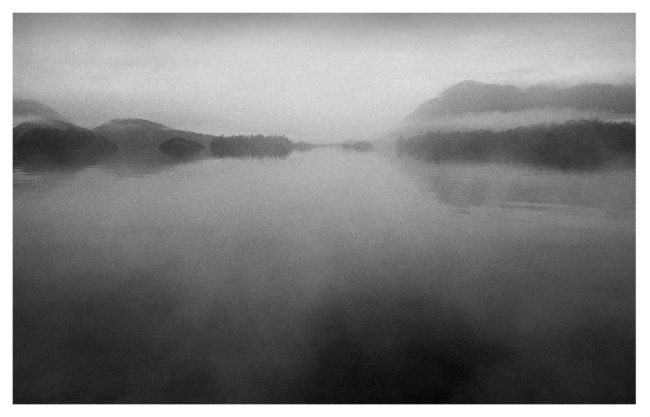

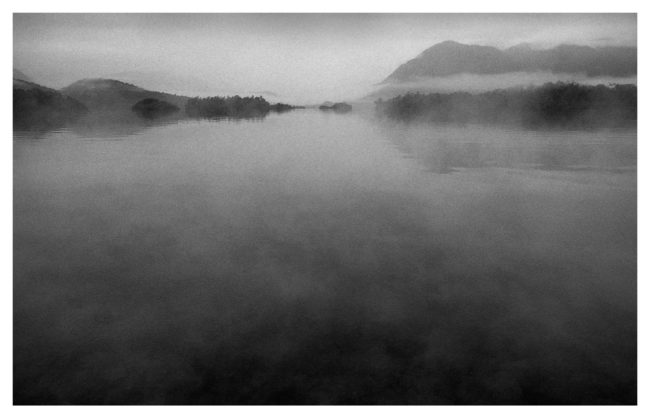

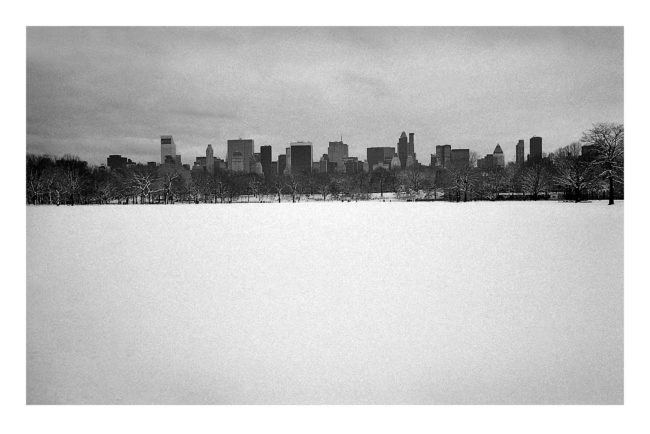

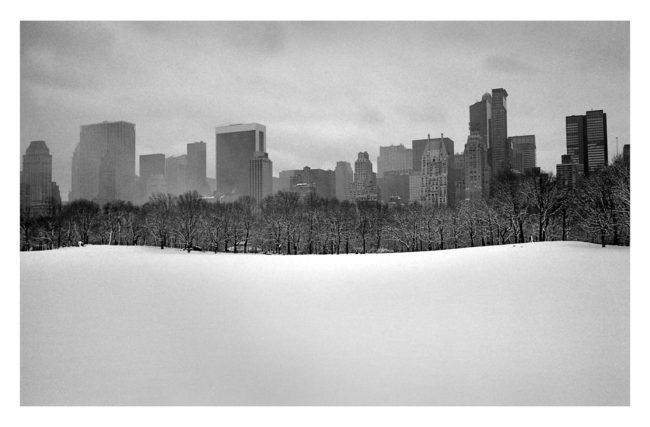

Desde sus primeros trabajos, Santiago Porter explora la representación de lo invisible y !paradoja o no! la fotografía es el medio que le abrió el paso en esa búsqueda. Las obras reunidas en esta exhibición conforman la serie titulada Bruma, una producción que se inició en el año 2007 y se compone de tres capítulos, que a modo de un libro, hilvanan una historia de devenir cíclico. En su primera etapa, los edificios públicos protagonizan un relato sobre su función en la vida social evidenciando su derrotero en la superficie de sus fachadas; así, el brillo de las puertas doradas del Ministerio de Economía al lado del Hospital Ferroviario con su aspecto decadente, dibujan el signo de la corrupción. El segundo conjunto de fotografías reúne monumentos que se volvieron obsoletos y, por ello, mucho más potentes en su carácter evocativo: marcas de perdigones en un paredón de ladrillo, letras de bronce sustraídas de lo que supo ser un homenaje a los caídos en Malvinas; Evita y Perón decapitados. Por último, bloques de hormigón hermético rodeados de kilómetros de pampa rasa y vacía, postes de luz sin conexión eléctrica, un bosque muerto y humeantes surcos de plantación de cañas de azúcar en un territorio donde hace no tanto tiempo comenzaba uno de los capítulos más sangrientos de nuestra reciente historia; paisajes que no merecen ser motivo de postal y que describen un país que construye ruinas ex profeso.

Es precisamente la recurrencia al contraste y las contraposiciones de sentido al límite del oxímoron lo que confiere la fuerza a estas obras; es el acto de fotografiar, el convertir la cosa en imagen lo que hace más tangible y presente la densidad de la historia. En este proceso, la presencia de la bruma es central, funciona como soporte de la potencia que adquieren las cosas al ser fotografiadas, permite ver, pero a la vez asigna un aspecto particular que opaca, y en ese velo aparece la historia que para Rancière se encuentra cifrada en cada imagen.

El verdadero destino de las imágenes de Santiago Porter es servir a una memoria constructiva que interpelando el pasado disponga el tablero para otro juego de la historia.