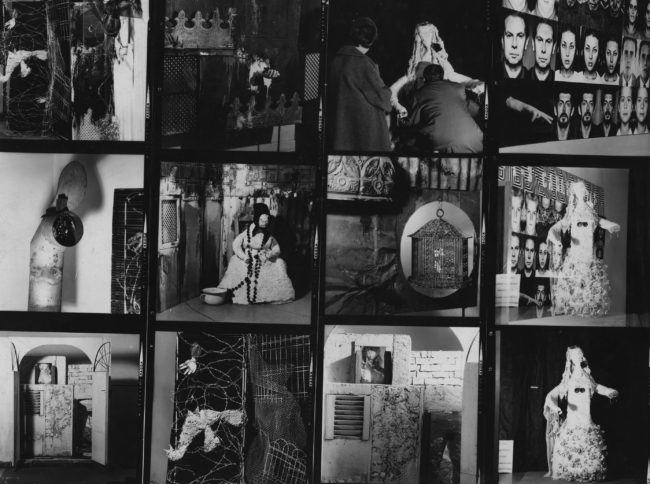

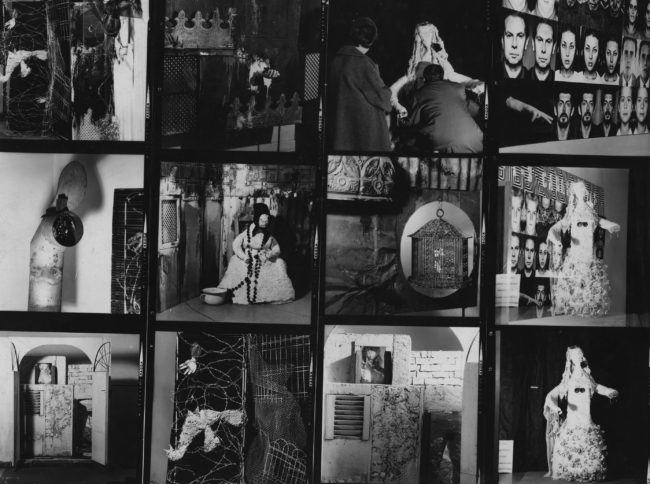

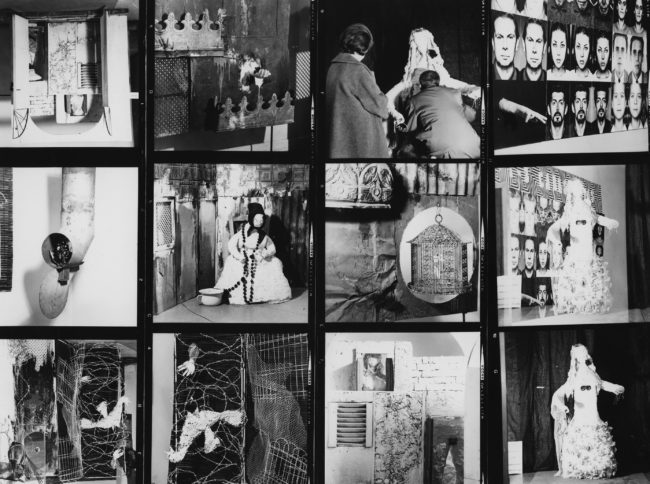

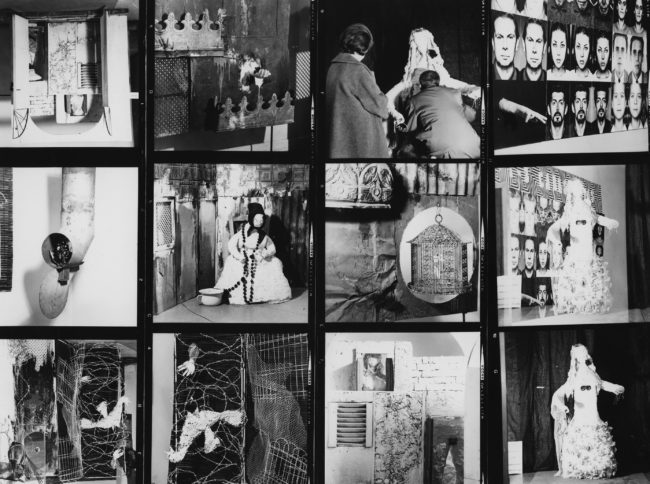

Concepción – Vida – Muerte y Transfiguración was a collective exhibition made up of Narcisa Hirsch, Walter Mejía, Marie Louise Alemann and Aldo Sessa that took place in 1966 at the Lirolay Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

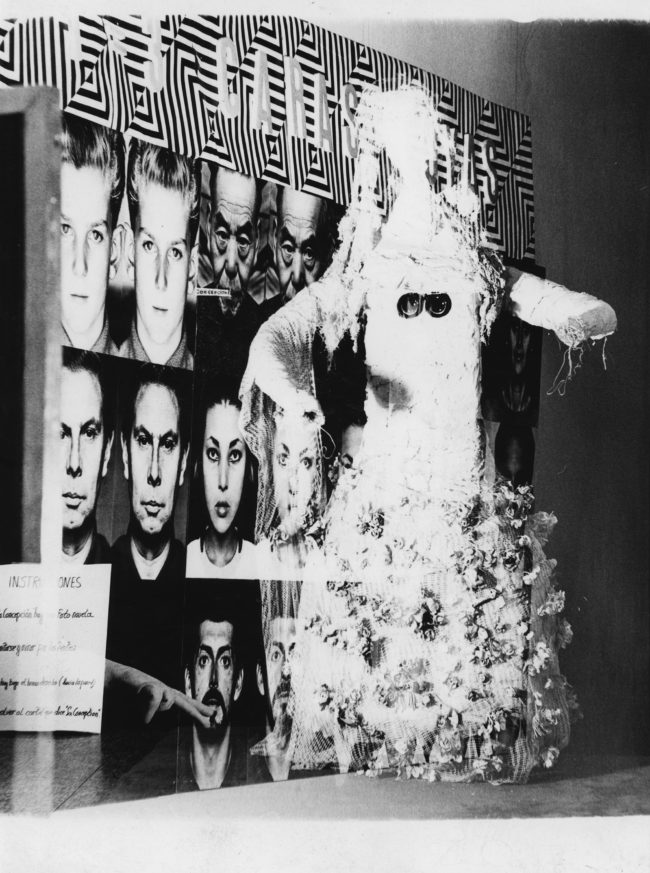

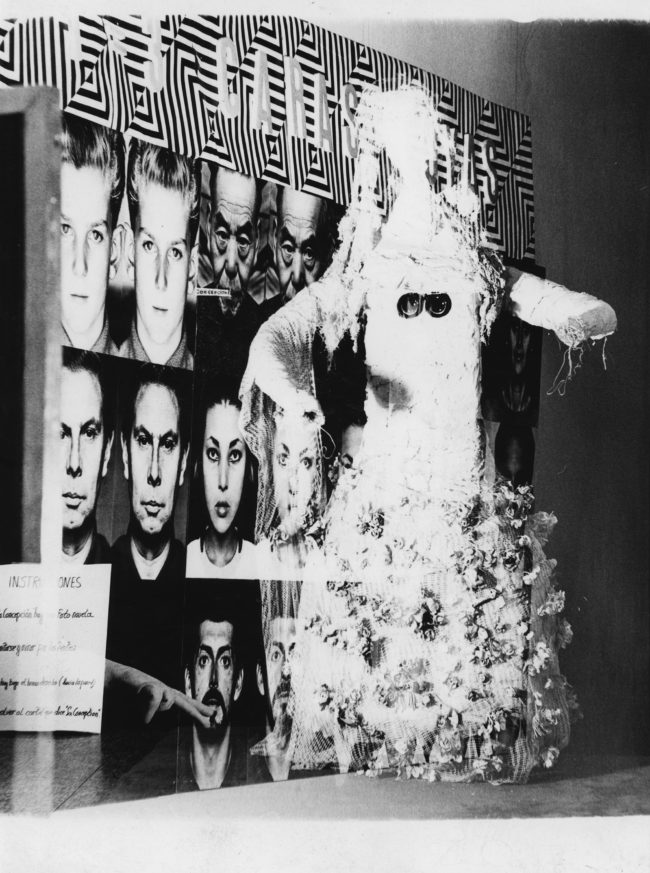

The show included a diverse range of visual materials: a promotional poster by Edgardo Giménez, an early sculpture by Narcisa Hirsch that included a series of stereoscopic photographs made with Marie Louise Alemann and Walter Mejía, a wall of photographic portraits by Alemann, and a selection of photographs by Aldo Sessa.

Concepción – Vida – Muerte y Transfiguración fue una exposición colectiva integrada por Narcisa Hirsch, Walter Mejía, Marie Louise Alemann y Aldo Sessa que tuvo lugar en 1966 en la Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

La muestra incluía una diversa gama de materiales visuales: un afiche promocional de Edgardo Giménez, una escultura temprana de Narcisa Hirsch que incluía una serie de fotografías estereoscópicas realizadas con Marie Louise Alemann y Walter Mejía, una pared de retratos fotográficos de Alemann y una selección de fotografías de Aldo Sessa.

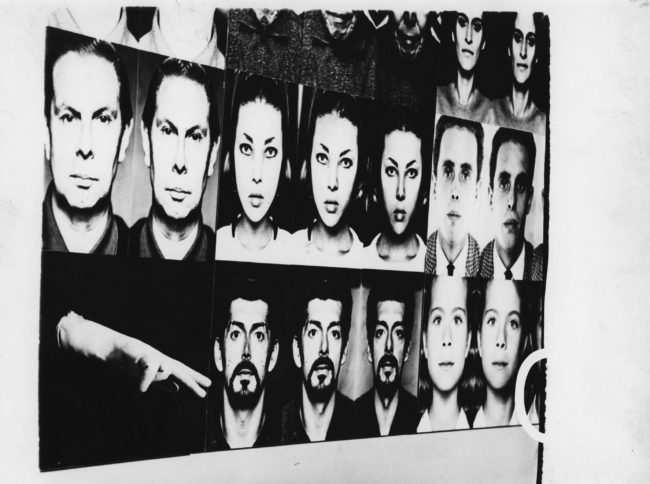

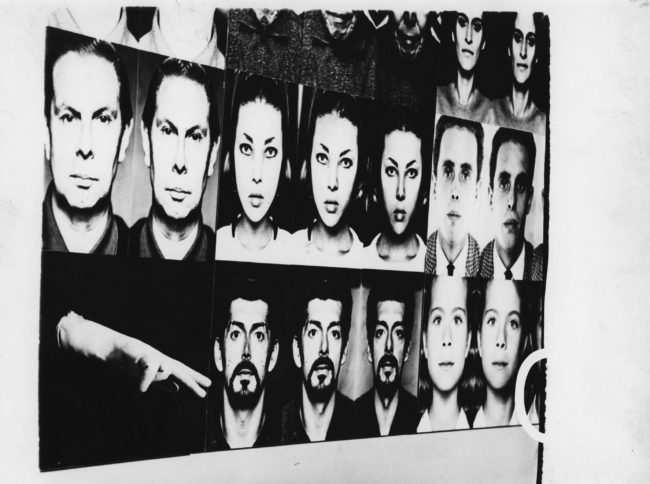

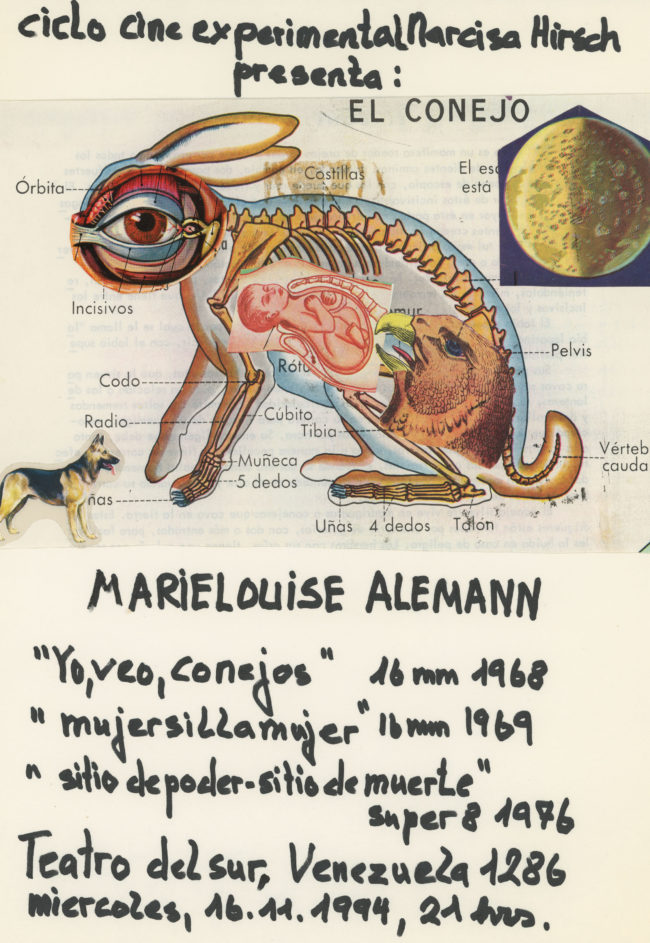

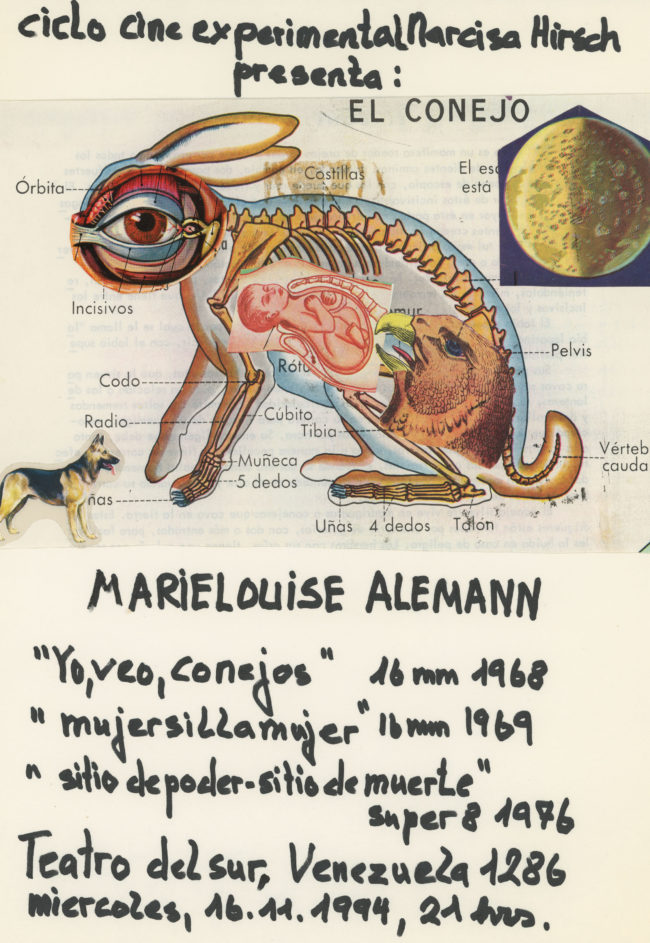

Yo veo conejos is Alemann’s first experimental film, where she extends her photographic exploration of faces to the cinema with a series of autobiographical portraits of people close to her, unlike anything seen in experimental Argentine cinema up to that point in its brief history.

“My first film was very static because I came from photography. It was called Yo veo conejos and its images are divided into three parts. The first (I) tries to show me as a person, my inner state; the second (I see) presents the nine characters that are somehow related to that part of me; they are very special faces, of people who surrounded me at that time, they are something like my inner characters. There is a face that is very aggressive, another one that is very crazy reflects my madness , a very intellectual gentleman, very German, he is my severe part, and so are the others. I was not aware of all this, I see it that way now. These two parts show a search for identity in the crowd, in the crowd symbolized by the rabbits , but it shows the attempt to get out of that state.” Marie Louise Alemann

Yo veo conejos es la primer película experimental de Alemann, donde extiende su exploración fotográfica de rostros al cine con una serie de retratos de personas cercanas a ella y autobiográficos, diferente a todo lo visto en el cine experimental argentino hasta ese momento de su breve historia.

“Mi primer film fue muy estático porque yo venía de la fotografía. Se llamaba Yo veo conejos y sus imágenes están repartidas en tres partes. La primera (Yo) trata de mostrarme como persona, mi estado interior; la segunda (Veo) presenta a los nueve personajes que de alguna manera están relacionados con aquella parte mía; son caras muy especiales, de gente que me rodeaba en aquel momento, son algo así como mis personajes interiores. Hay una cara que es muy agresiva, otra muy loca refleja mi locura, un señor muy intelectual, muy alemán, es mi parte severa, y así los demás. Todo eso no era consciente, lo veo así ahora. Estas dos partes muestran una búsqueda de la identidad en el gentío, en la muchedumbre simbolizada por los conejos, pero muestra el intento por salir de ese estado.” Marie Louise Alemann

Marabunta was an action carried out by the group made up of Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann and Walther Mejía, which took place on October 31, 1967 at the Teatro Coliseo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, the night of the premiere of Blow Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966).

Hirsch’s film Marabunta (1967), with camera and editing by Raymundo Gleyzer and music by Edgardo Varese, records the collective anthropophagy ceremony that transformed the cinema audience into active participants in an action centered around a sculpture – also built by the group – of a six-meter skeleton completely covered with fruit and food, which contained live pigeons and parrots painted in phosphorescent colors that flew out while people ate.

Marabunta fue una acción realizada por el grupo compuesto por Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann y Walther Mejía, que tuvo lugar el 31 de Octubre de 1967 en el Teatro Coliseo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, la noche del estreno de Blow Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966).

La película Marabunta (1967) de Hirsch con cámara y edición de Raymundo Gleyzer y música de Edgardo Varese, registra la ceremonia de antropofagia colectiva que transformó al público del cine en participantes activos de una acción centrada alrededor de una escultura – construida también por el grupo- de un esqueleto de seis metros recubierto por completo de fruta y comida, que contenía en su interior palomas y cotorras vivas pintadas con colores fosforescentes que salían volando mientras la gente comía.

Manzanas was an action carried out by the group made up of Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann and Walther Mejía in 1969 on Florida Street and Diagonal Norte, Buenos Aires, Argentina. In the action, the group distributed hundreds of apples to the people who walked the street under the premise of: “This apple is different from every day / we do the work with the people / the work is the shared moment”.

Manzanas fue una acción realizada por el grupo compuesto por Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann y Walther Mejía en 1969 en la calle Florida y Diagonal Norte, Buenos Aires, Argentina. En la acción el grupo repartió cientos de manzanas a las personas que recorrían la calle bajo la premisa de: “Esta manzana es distinta a la de todos los días / hacemos la obra con la gente / la obra es el momento compartido”.

The experimental film Portrait of an Artist as a Human Being (1973) returns to the objects, actions and films made over the years by the group made up of Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann and Walter Mejía, to close the chapter of their work in collaboration.

As in a ritual, through video performances in Hirsch’s workshop, the beach and other places, the group throws into the river the different elements that have intervened in the actions they have carried out together over a period of time.

La película experimental Retrato de una artista como ser humano (1973) vuelve a los objetos, acciones y filmaciones realizados a lo largo de los años por el grupo compuesto por Narcisa Hirsch, Marie Louise Alemann y Walter Mejía, para cerrar el capítulo de su trabajo en colaboración.

Como en un ritual, mediante videoperformances en el taller de Hirsch, la playa y otros sitios, el grupo va tirando al río los distintos elementos que han intervenido en las acciones que han realizado en conjunto a lo largo de una época.

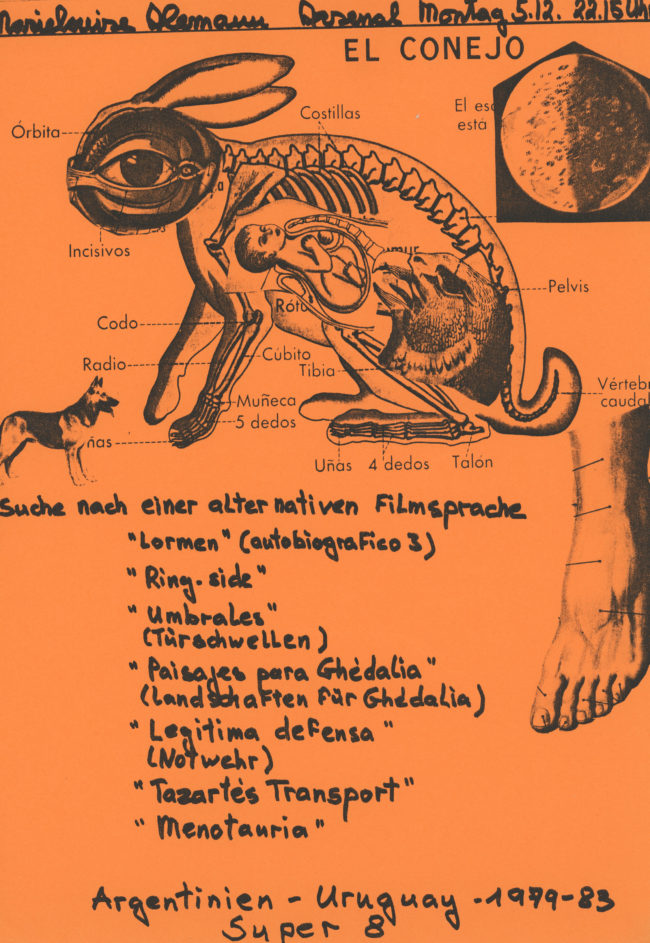

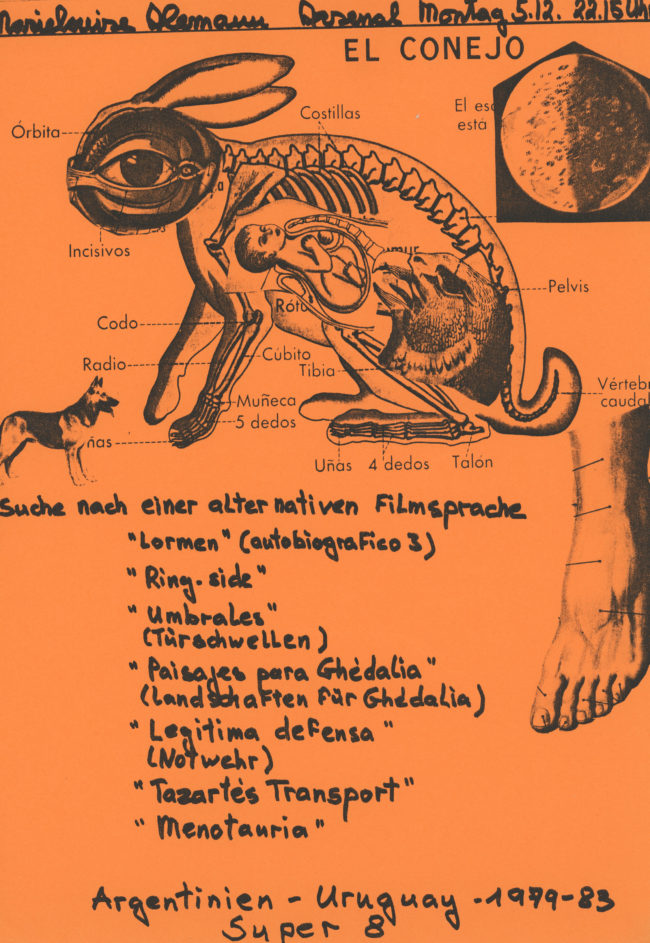

Butoh’s influence on Marie Louise’s work can be seen in several of her films, but never as strongly as in Legítima defensa. In this film, Marie Louise expressed her appreciation for confrontational artistic possibilities that could leave the viewer deeply distressed and confused. The eight minutes of duration are completely dominated by images of the filmmaker, who is shown in a menacing way wielding a wooden cane, wearing a shower cap and contorting her face for the camera while the soundtrack accompanies her with growls.

Through the Super 8 format, Legítima Defensa delves into the psychology of people in the repressive context of the last military dictatorship. Alemann’s descriptions of this film varied over the years, in part because he preferred to present the meanings of his works as open. For example, he has characterized his short film as “a vision of madness as the only defense in a world of chaos.” However, years later, he elaborated on his motivating ideas in an unpublished interview: “It was from that time: the aggression that came from the camera and the aggression of the character that finally disappears through the intensity of the light. What I thought at that time is that in situations like the ones Argentina was going through, and also in Germany, a technique could have been to disappear for the enemy. Turn invisible. Spin the character who is prepared to fight and at the same time is watching.”

La influencia de Butoh en la obra de Marie Louise se puede observar en varias de sus películas pero nunca de manera tan contundente como en Legítima defensa. En esta película, Marie Louise expresó su aprecio por las posibilidades artísticas de confrontación que podrían dejar al espectador profundamente angustiado y confundido. Los ocho minutos de duración están completamente dominados por imágenes de la cineasta, que se muestra de manera amenazante empuñando un bastón de madera, con un gorro de baño y contorsionando su rostro para la cámara mientras la banda sonora la acompañan con gruñidos.

Por medio del formato Super 8, Legítima defensa profundiza en la psicología de las personas en el contexto represivo de la última dictadura militar. Las descripciones de Alemann sobre ésta película variaron a lo largo de los años, en parte porque prefería presentar los significados de sus obras como abiertos. Por ejemplo, ha caracterizado su corto como “una visión de la locura como única defensa en un mundo de caos”. Sin embargo, años más tarde, elaboró sus ideas motivadoras en una entrevista inédita: “Era de aquella época: la agresión que venía de la cámara y la agresión del personaje que al fin desaparece a través de la intensidad de la luz. Lo que yo pensé en esa época, es que en situaciones como las que estaba pasando la Argentina, y también en Alemania, una técnica podría haber sido desaparecer para el enemigo. Hacerse invisible. Hacer girar al personaje que está preparado para luchar y al mismo tiempo está observando”.