Reconocida artista del Pop Art, la moda y el arte conceptual, Dalila Puzzovio desarrolla su carrera en el panorama local e internacional desde los años 60, vinculada fundamentalmente al ambiente creativo del Instituto Di Tella de Buenos Aires. Su primeros trabajos con los emblemáticos “yesos” en la muestra “El hombre antes del hombre” (1962), da el puntapié inicial para un corpus de obras donde los objetos cobran un rol protagónico en su doble sentido como cosas externas pero también como cosas que le pasan al sujeto. Sus “Cáscaras” (1963) ortopédicas –restos de descarte obtenidas del Hospital Italiano- eran portadoras del aura de los cuerpos que las utilizaron, representaban un tipo de readaptación médica, una reelaboración de una situación traumática, un monumento al dolor que sugiere una reflexión sobre la ruptura y los órdenes fracturados.

Superando los límites e influencias del Informalismo, Pop-art y Neo-dadá, con un gesto genuino y audaz, Puzzovio es pionera en la ruptura de los compartimentos estancos entre las artes plásticas, las artes visuales, la moda, el diseño, la arquitectura y su impacto en la vida cotidiana. En obras tales como “Dalila doble plataforma” (1967), “Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen” (2019) la artista toma las calles, se apropia de la vía pública, interviene en la praxis vital del espectador y cuestiona las leyes del “mundo del arte” cuando exhibe en locales comerciales sus zapatos de doble plataforma en colores fluorescentes como si fueran objetos de consumo masivo o bien incorpora la performance recreando puestas en escena citadinas, contrastando el entorno urbano con la acción artística. Un corpus de obra con una fuerte impronta editorial, trabajo de archivo y documentación atravesado por una mirada reflexiva contemporánea, que pone de manifiesto la versatilidad de Puzzovio, produciendo en las distintas ramas de las artes, sin respetar fronteras y ejerciendo una mirada libre, de carácter irreverente, propia de su quehacer artístico y la efervescencia de la época a la cual representa.

Nacida en 1943, Dalila Puzzovio, ganó prominencia e importancia en su carrera artística en Argentina por fusionar Pop Art, El diseño de modas y el arte conceptual.

Entre 1955 y 1962 estudió con el pintor surrealista Juan Batle Planas (1911-1966) y el artista conceptual Jaime Davidovich (1936-2016). Su primera exhibición en 1961 en la galería Lirolay, Buenos Ares, consistía en pinturas. Para su segunda exhibición “Cascaras” 1963, ella mostró esculturas realizadas con yesos descartados de hospitales y otros objetos. Puzzovio se refería a estas esculturas como “cáscaras astrales” porque ella sentía que éstas retenían el aura de los cuerpos que una vez sostuvieron y eran, por tanto, un tipo de ready-made médico.

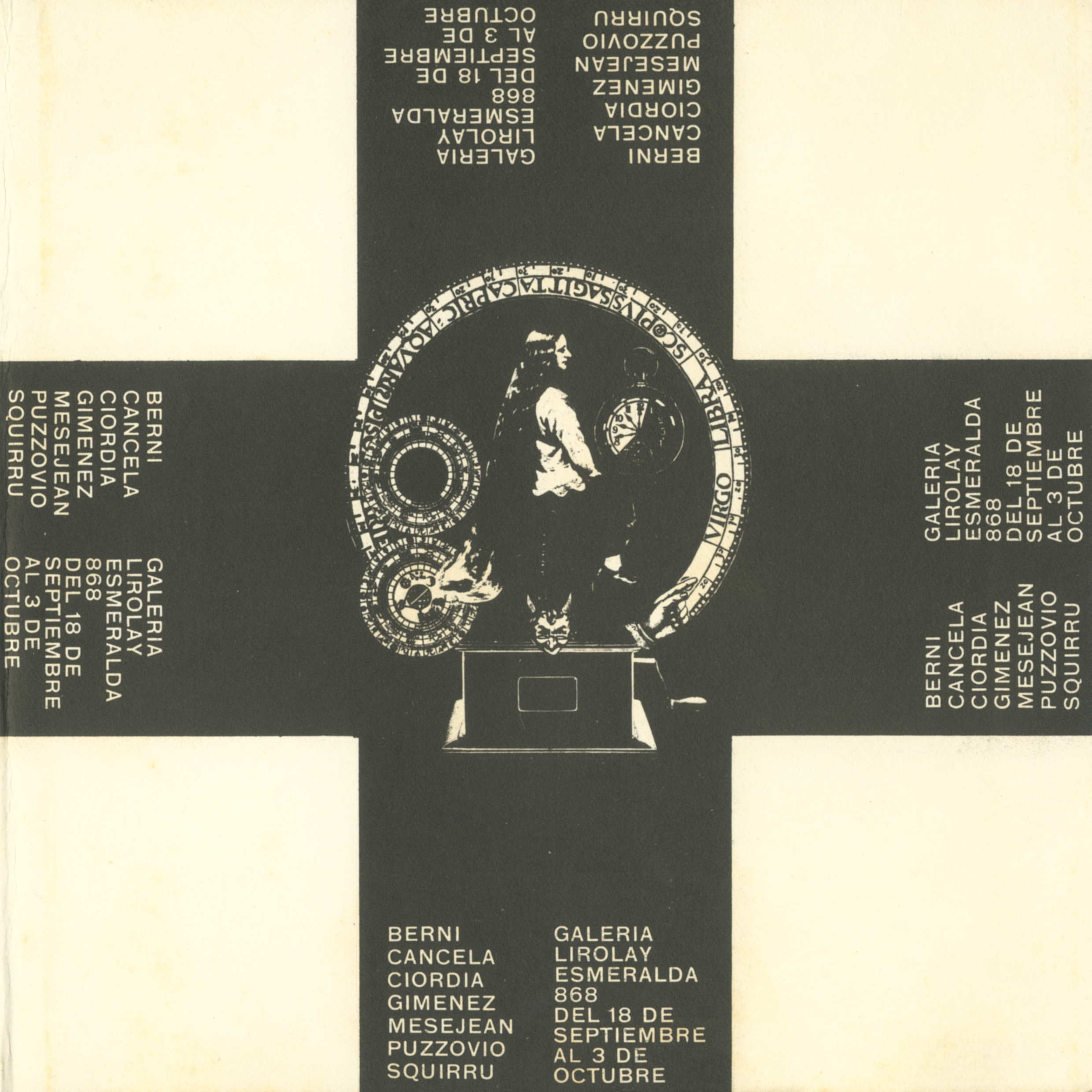

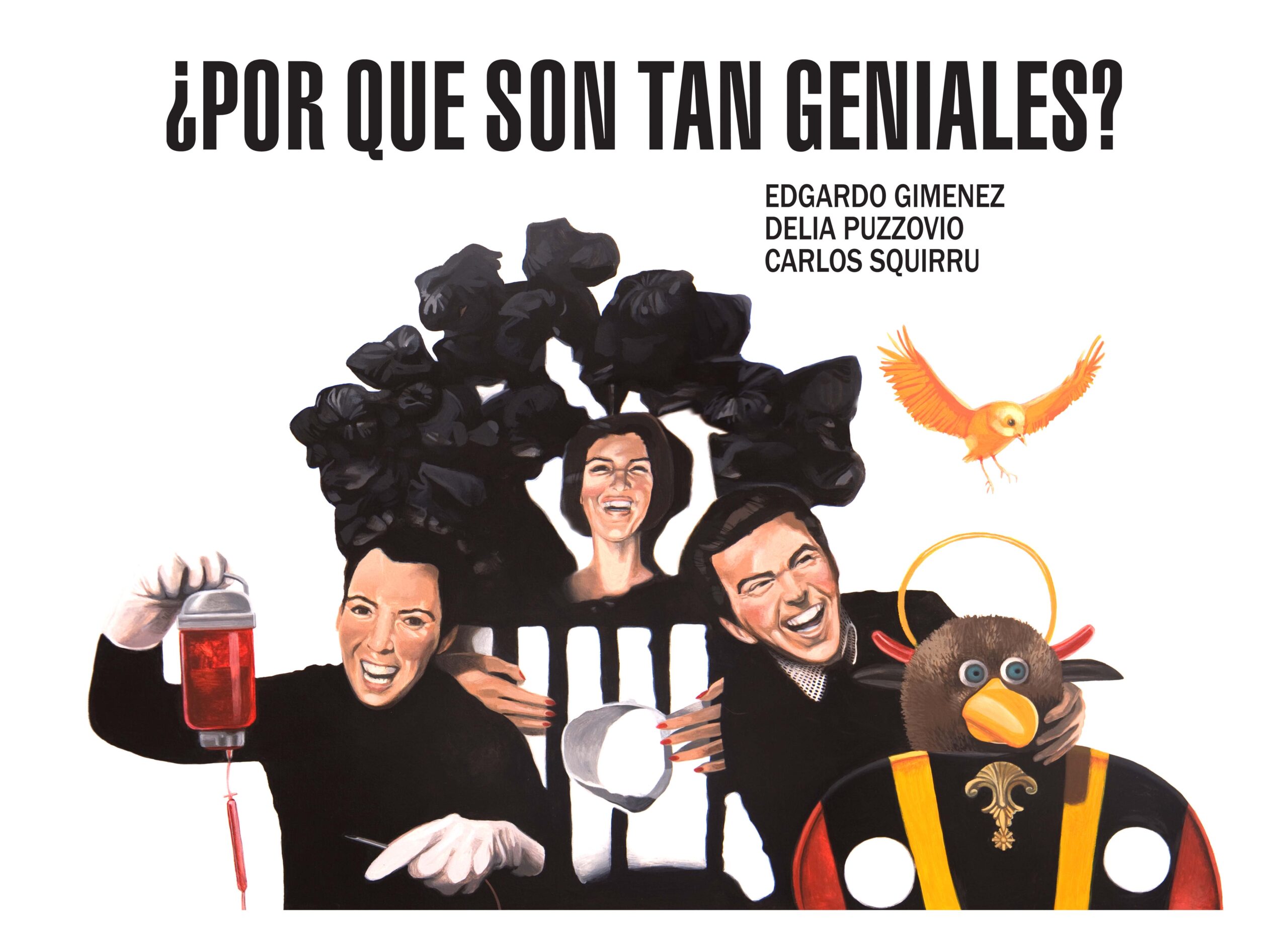

Dalila fue una de las treinta artistas en participar de la exposición “New Art of Argentina” que tuvo lugar en 1964, organizada por el Walker Art Center en Minneapolis y el Instituto Torcuato Di Tella en Buenos Aires. Durante 1960 muchos artistas desarrollaron Pop- Art, incluyendo a Puzzovio, Edgardo Gimenez ( b.1942), y al marido de Puzzovio, Carlos “Chary” Squirru (1934), con quienes ella colaboró en acciones artísticas que fusionaron performances con la vida diaria. En 1965, por ejemplo, el trío desarrolló un cartel de gran formato de propaganda que instalaron en la intersección de dos de las principales avenidas de Buenos Aires que leía “Porque son tan geniales?” escrito sobre sus caras. El mensaje era una publicidad que ellos mismos llevaron a cabo en un acto de ironía para sus trayectorias. Luego después Puzzovio comenzó a recibir múltiples premios y reconocimientos. Primero el Premio Nacional Di Tella por su Autorretrato ( Autorretrato de Dalila, 1966) realizado por pintores comerciales incorporando a la imagen el retrato de una famosa modelo internacional – Veruschka- que causalmente tenía un parecido con Puzzovio. Un año después, en 1967, Puzzovio fue reconocida con el Premio Internacional Di Tella por su trabajo: Dalila doble plataforma que consistió en dieciséis pares de zapatos de mujer con plataforma. Los zapatos podían ser exhibidos tanto en galerías de arte como en locales comerciales. Con el siguiente trabajo Puzzovio se sumergió en la mezcla del arte y la moda, una categoría específica del Pop Art practicada por ella y por la artista Delia Cancela(b.1940) junto a Eduardo Costa (b.1940). Hasta 1985 Dalila Puzzovio diseño disfraces y vestuario de teatro y trabajo en la industria de la moda. Durante los años 80’ y los 90’ contribuyo en múltiples proyectos de arquitectura de interiores. Hasta 1990 trabajo también en varias revistas tanto como ilustradora como con notas. Su obra hoy pertenece a colecciones públicas y privadas tales como al Centro de Artes Visuales del Instituto Di Tella, Buenos Aires; Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires, entre otros. Puzzovio vive y trabaja en Buenos Aires, Argentina.

El año siguiente, la combinación entre belleza y oscuridad, entre la elegancia y lo siniestro, pasó a las tres dimensiones. En el mismo movimiento, una preocupación que sería clave en el resto de su obra ocuparía el centro de la escena: el cuerpo como una materia plástica, de contornos imprecisos, hecha de partes desmontables de orígenes diversos y, por ende, modificables para crear formas inauditas.

El cuerpo y su imagen, en Dalila Puzzovio, serían desde entonces un escenario de metamorfosis e invención. Sobre todo cuando se trataba de un cuerpo atribuido a un personaje típicamente femenino, como en este caso lo es La novia. Se trata de la pieza con la que Dalila participó de la mítica exposición El hombre antes del hombre y consistía en una escultura que combinaba trozos de caños, retazos y, por primera vez, yesos ortopédicos, para conformar un ser de escala humana. Además, la muestra sería la oportunidad para un temprano cruce entre arte y moda, una fusión que Puzzovio muy pronto transformaría en un nudo central de su práctica

De la serie La novia

Sin título

Año 1962

Fotografía

Copia de época

Copia cromogénica

Dimensiones 17,9 x 23,6 cm.

Colección privada

Dalila Puzzovio

La feroz gracia de los yesos de Delia Puzzovio extraídos del Hospital Italiano, donde vio la posibilidad a ese material torturado de darle una trascendencia hedonista y construyó con ellos sus cochecitos de miembros destartalados o las piernas ortopédicas sobre el cajón de lustrar botines. (…)

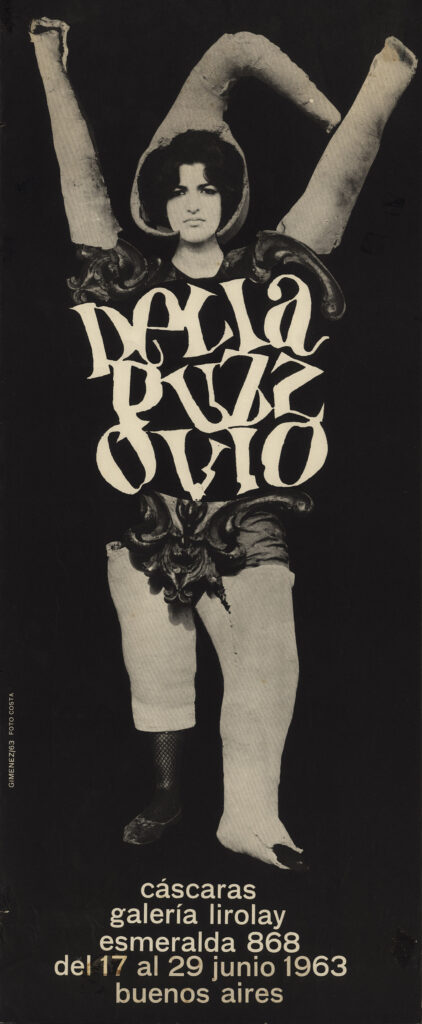

Aquellos yesos a los que refiere fueron la obra central de una de sus exhibiciones más recordadas que se tituló Cáscaras (1963), montada en la mítica y vanguardista galería Lirolay. Fue en realidad una instalación, donde presentó objetos realizados con yesos ortopédicos rescatados de la basura del Hospital Italiano, entre recepcionistas con uniformes de enfermeras que recibían a los invitados y les pedían que hicieran silencio.Este monumento al dolor, sugiere una reflexión sobre la ruptura y los órdenes fracturados; una superación de las influencias del Informalismo, Pop-art y Neo-dadá, que marcaron su trayectoria, generando un gesto genuino y audaz.

De la Serie Cáscaras

Afiche

Año 1963

Publicidad de la exposición “Cáscaras”, Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Copia de época

Impresion Offset sobre papel obra

Dimensiones 59 x 24,2 cm

Dalila Puzzovio & Edgardo Gimenez

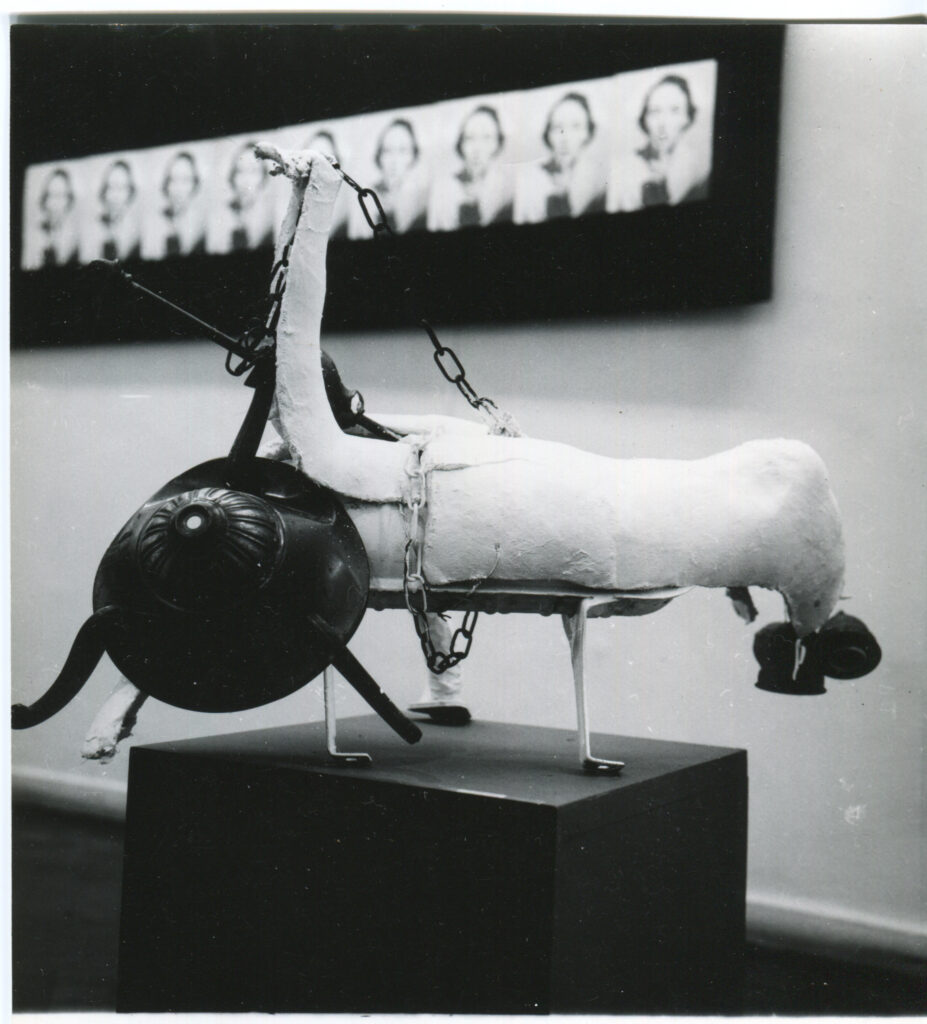

De la serie Cáscaras

Lustrabotas

Año 1963

Objeto

Técnica mixta (Yesos ortopédicos, madera & telas)

Dimensiones 62 x 28 x 20 cm.

Pieza única

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

Año 1963 / 1998

De la serie Cáscaras

Sin título

Año 1963

Atelier Squirru – Puzzovio

Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1963

De la serie Cascaras

Lleno de sonrisas serias

Año 1963

Objeto

Técnica mixta (Yesos ortopédicos, metal y madera)

Dimensiones variables

Fragmento I 87 x 85 x 57 cm. | Final 221 x 96 x 57 cm. x 37,8 x 22,4 in.

Pieza única

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

Año 1963 / 1998

De la serie Cáscaras

Sin título

Año 1963

Atelier Squirru – Puzzovio

Buenos Aires, Argentina

De la serie Cáscaras

Sin título

Año 1963

Vista parcial Instalación “Cascaras”, Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, Argentina

La primera vez que fui con papá a la ciudad de Montevideo en el año ‘55, algo ocurrió en la vecindad de ese Hotel Central. Una gran acumulación de coloridas energías entrelazaban fuerzas que se convertían en coronas mortuorias.

Visualmente eran una demanda provocadora y enigmática ya que no eran de flores naturales sino de representaciones de plástico casi planas.

Este enfrentamiento al ritual humano, me reveló un vocabulario que sobre todas las definiciones me entregaba un sentido de lo dramático fresco; podía sumergirme en un mundo rudimentario, donde las envolturas, las cintas y las letras doradas me permitieron sueños individuales en términos fluidos, una conexión crucial de misterio y poder alegórico.

Al instalarse estas coronas, inmediatamente dan la sensación de que algo está ocurriendo en la vecindad. Algún episodio dramático de la vida real.

La fantasía se hace aún más increíble, caos y orden en bizarra proporción.

De la serie La muerte

Afiche

Año 1964

Publicidad de la exposición “La muerte”, Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Copia de época

Impresion Offset sobre papel obra

Dimensiones 59 x 24,2 cm

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio & Edgardo Gimenez

De la serie La Muerte

Corona para los habitantes no humanos

Año 1964 – 1998

Objeto

Técnica mixta ( Yeso ortopédico, vinilo y tela )

Dimensiones variables

(97 x 77 x 34 | 38,1 x 30,3 x 13,4 in.)

Pieza única

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie La Muerte

Sin título

Año 1964

Atelier Squirru – Puzzovio

Buenos Aires, Argentina

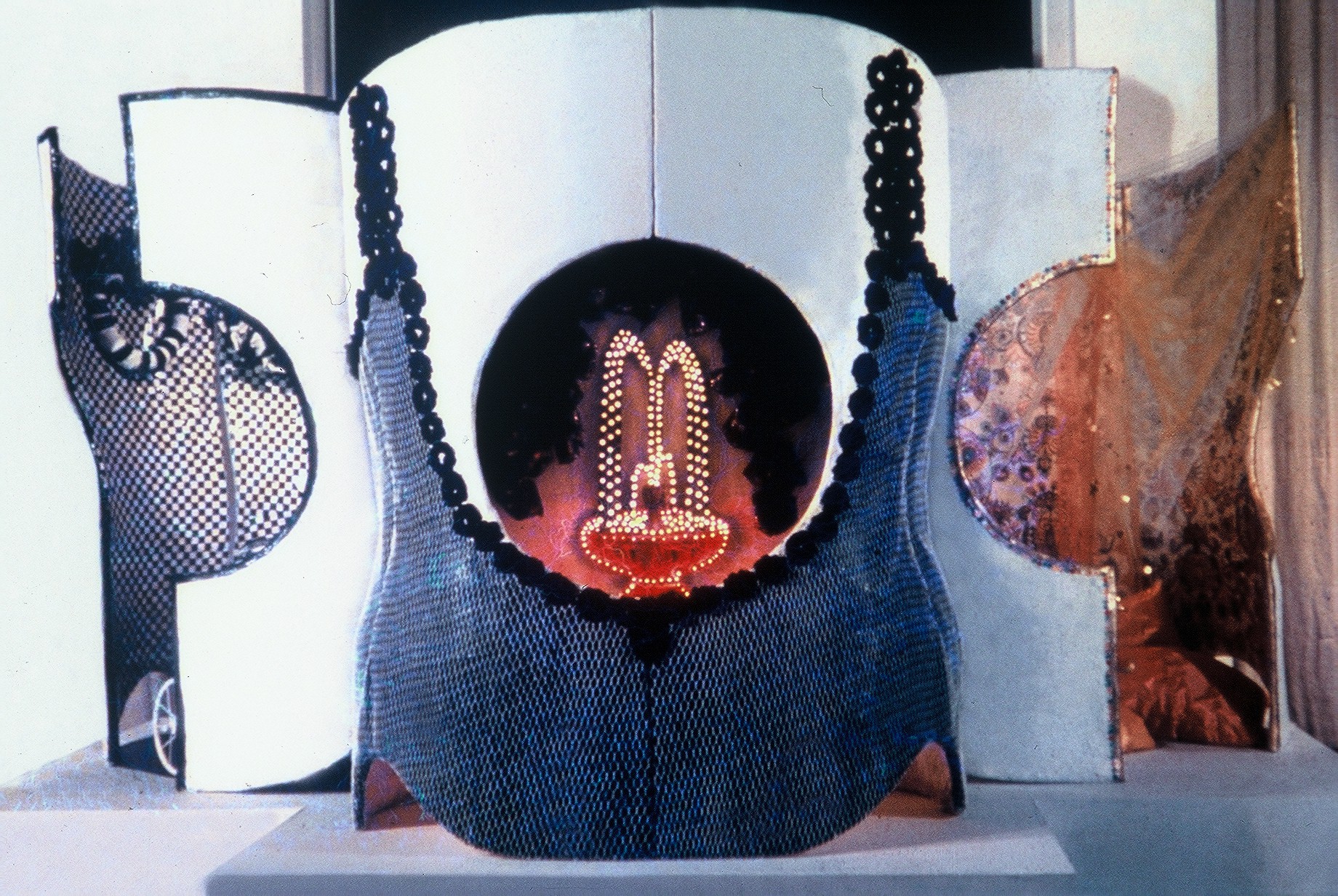

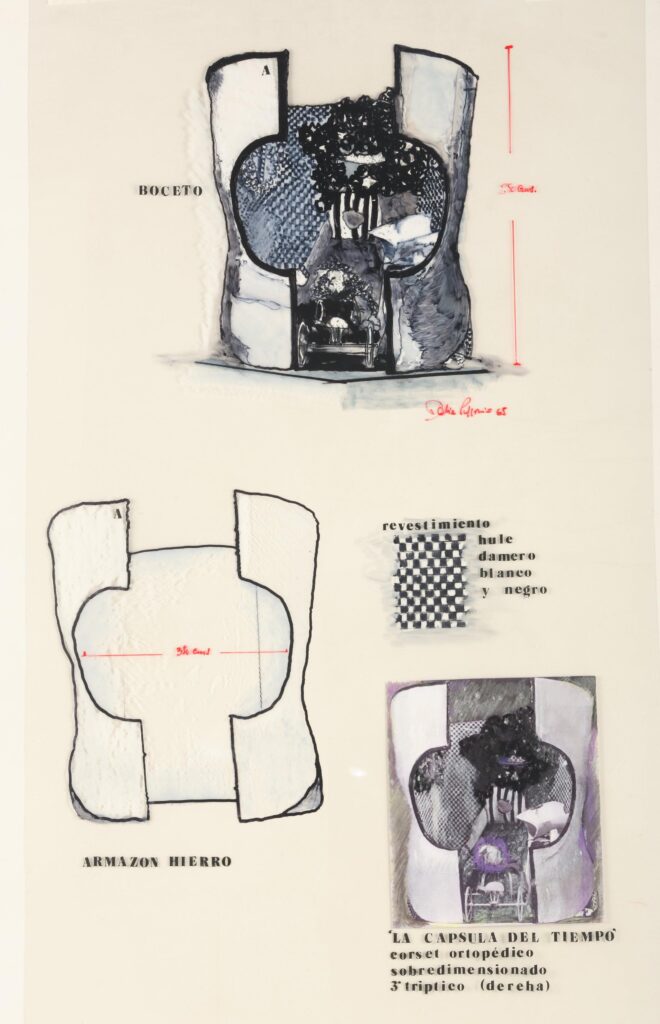

En 1965, Puzzovio llevó al centro de la escena el diseño del espacio de exhibición de su propia obra. Invitada a participar del Premio Di Tella, presentó una gran instalación consistente en tres estructuras de dos metros por dos metros y medio, realizadas en alambre y yeso, que sugieren la forma de corsets gigantes. Elevadas sobre una plataforma, las estructuras son, al mismo tiempo, “obra” y dispositivo de montaje: son tanto aquello a ser visto como aquello que da a ver.

Una de ellas, llamada La esfera del tiempo, mostraba sobre sus muros y en su interior una serie de yesos y coronas realizados por la artista el año previo. En otra que tenía el título Se dan clases de tejido a mano y a máquina, Dalila dispuso una serie de almohadones y telas suaves. La restante, Jean Shrimpton, la plus belle fille du monde, era un homenaje a la modelo del título. Tenía un enorme tejido en su exterior que sugería la forma de un corset y, a través de un agujero, se veía un juego de luces en el interior.

De la serie Dibujos para recortar y armar

Corset

Año 1973

Técnica mixta, tinta sobre acetato

Dimensiones 12,8 x 9,6 cm.

Pieza única

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

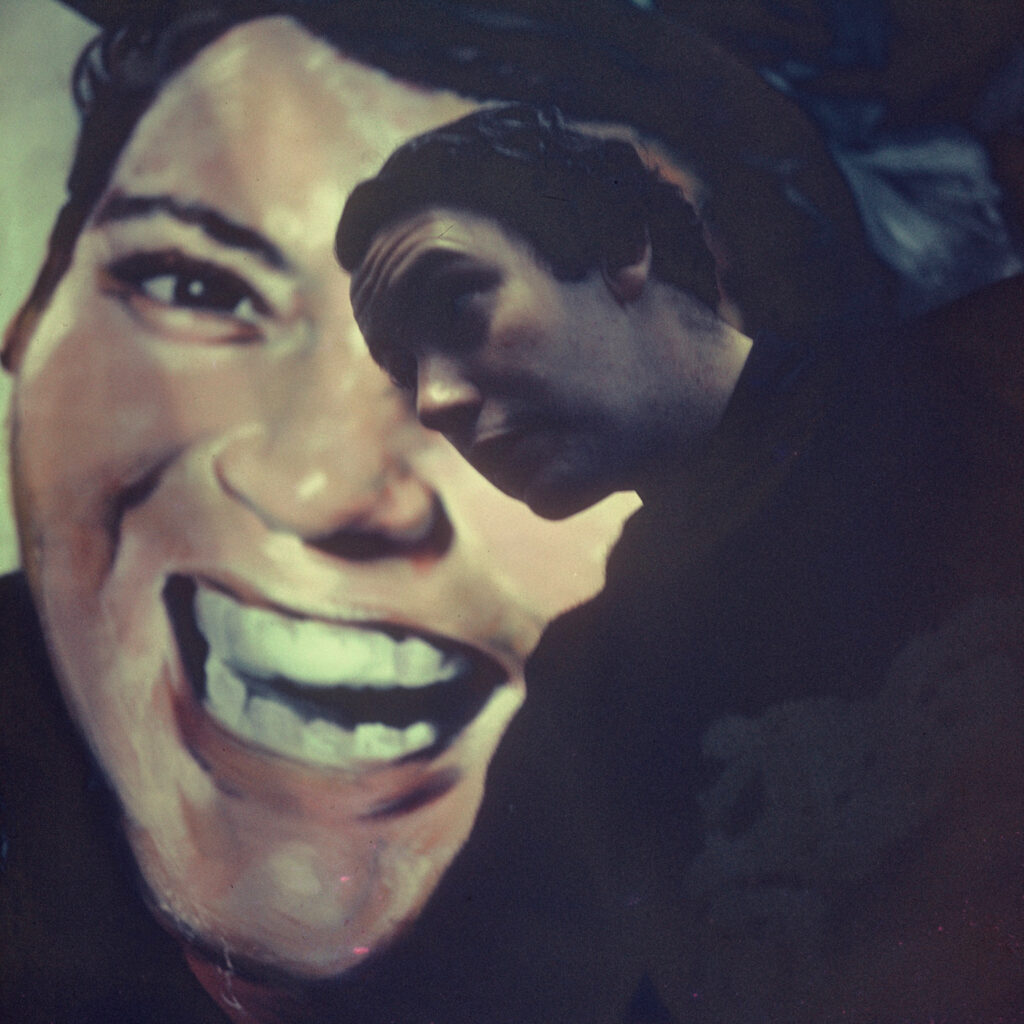

Una de las manifestaciones más emblemáticas fue la intervención publicitaria en Buenos Aires el 16 de agosto de 1965. Un cartel en un edificio en la esquina de Córdoba y Viamonte mostraba a Dalila junto a Charlie Squirru y Edgardo Giménez, cada uno portando objetos asociados a sus obras icónicas (una corona, elementos para una transfusión de sangre y un mono de peluche, respectivamente), con la leyenda: “¿Por qué son tan geniales?”.

Esta acción, complementada con la distribución de panfletos y documentada tanto en la prensa como en diapositivas, es una temprana exploración de la relación entre arte, medios masivos y mercadotecnia, un vínculo que en la Argentina se intensificaría en los años posteriores.

De la serie ¿Por qué son tan geniales?

Sin Título

Año 1965

Fotografía

Copia de época

Colección privada

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie ¿Por qué son tan geniales?

Sin Título

Año 1965

Fotografía

Copia de época

Colección privada

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie ¿Por qué son tan geniales?

Sin Título

Año 1965

Fotografía

Copia de época

Colección privada

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie ¿Por qué son tan geniales?

Sin Título

Año 1965

Fotografía

Copia de época

Colección privada

Dalila Puzzovio

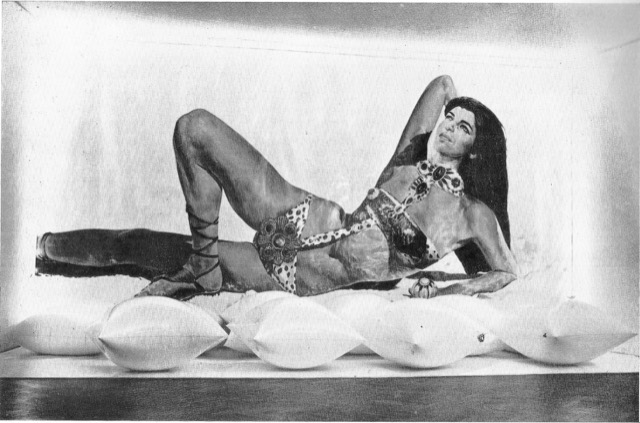

El Autorretrato de Dalila Puzzovio (1966-1997), segundo Premio Di Tella 1966, pintado por artesanos afichistas de cine, deviene una documentación de autorretrato, en gran formato, con objetividad iconográfica, en difusión y en prolongación de los medios de comunicación masiva, y en exhibición en un espacio de arte, ambiente poco usual para un poster panel.

Un collage, con el cuerpo de Verushka, una de las primeras top models del mundo, marcada por ornamentos de piedras de considerable tamaño, que se integran por la forma y el color, sobre la piel bronceada y el dorado de la arena de la playa y el mar como telón de fondo. La figura de Verushka, con rostro de Dalila, recostada con aire relajado, y a la vez en pose desenvuelta y seductora, se ilumina con bombillas de camarín en su marco exterior y se exponen, delante, almohadones inflables de plástico. Luego de exhibirse para el premio Di Tella 1966, en en Instituto Torcuato Di Tella en la calle Florida, la pieza desapareció. Realizada por los mismos artesano que realizaron el primer y original Poster-panel, Puzzovio hizo el remake de la obra en el año 1997, que es la pieza que se conserva y se ha exhibido en innumerables exposiciones a la fecha.

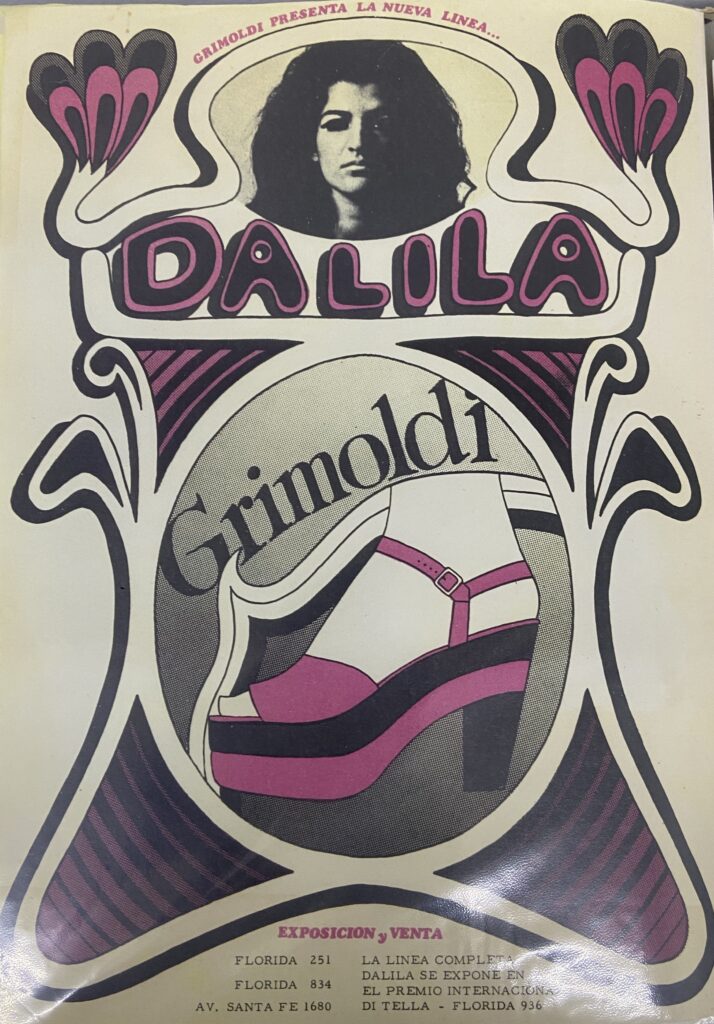

Doble Plataforma consiste en 16 pares de zapatos expuestos en cubos de acrílico dentro de un gran exhibidor de acero e iluminado en su interior. “Lo propuse como un work in progress porque el jurado internacional tuvo que ver, primero la obra en el Di Tella, y luego recorrer las sucursales de la zapatería Grimoldi de la calle Florida o de la Av. Santa Fe para ver el zapato como objeto de consumo. La idea era obra de arte-consumo / consumo-obra de arte”, recuerda Puzzovio.

De la serie Doble plataforma

Afiche

Año 1967

Publicidad de Doble Plataforma

Copia de época

Impresion Offset sobre papel obra

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

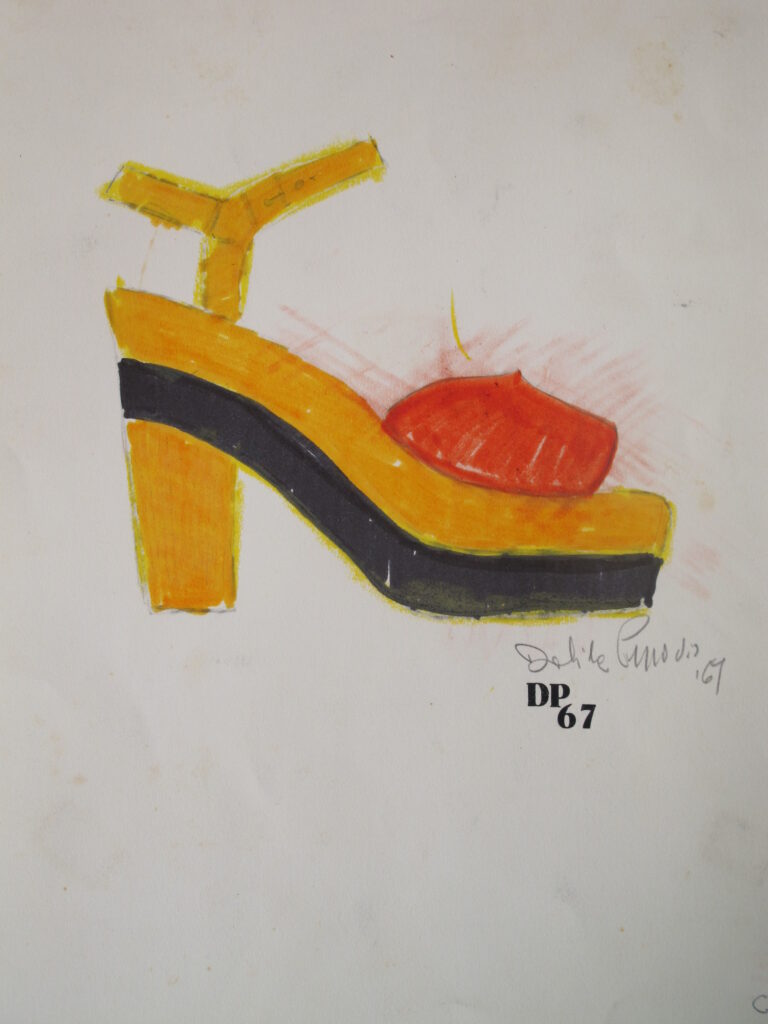

De la serie Doble plataforma

Boceto – Diseño de doble plataforma

Año 1967

Pieza única

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

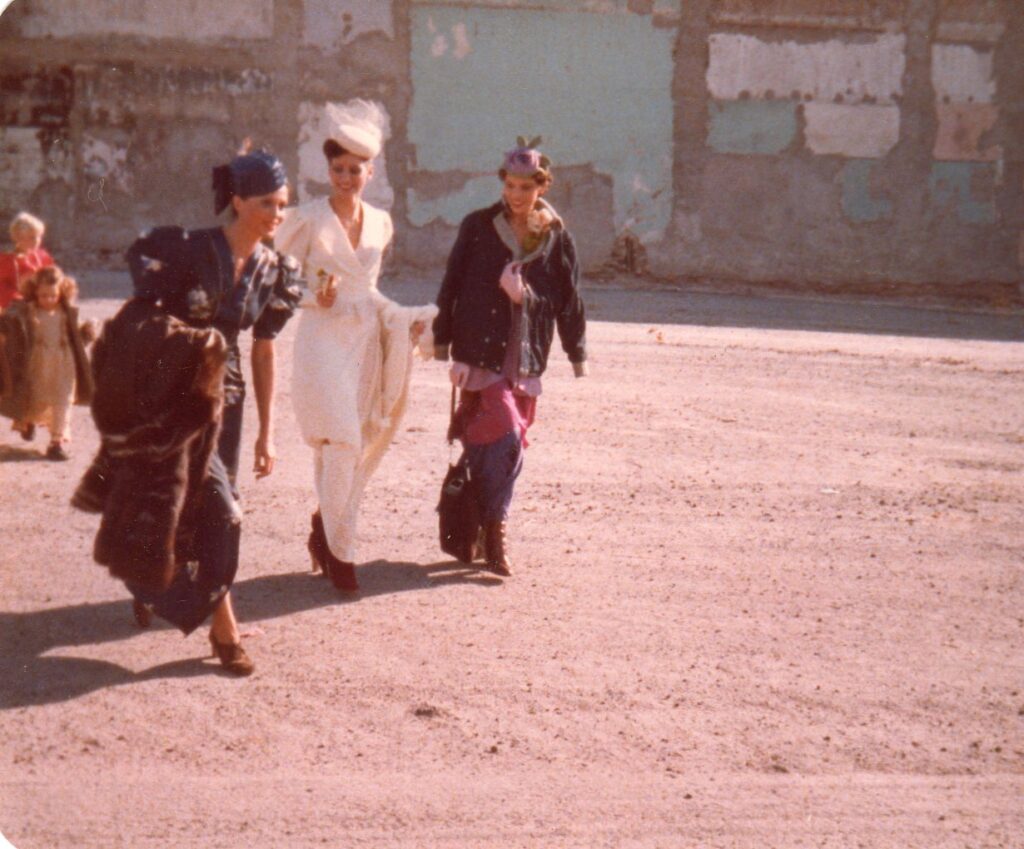

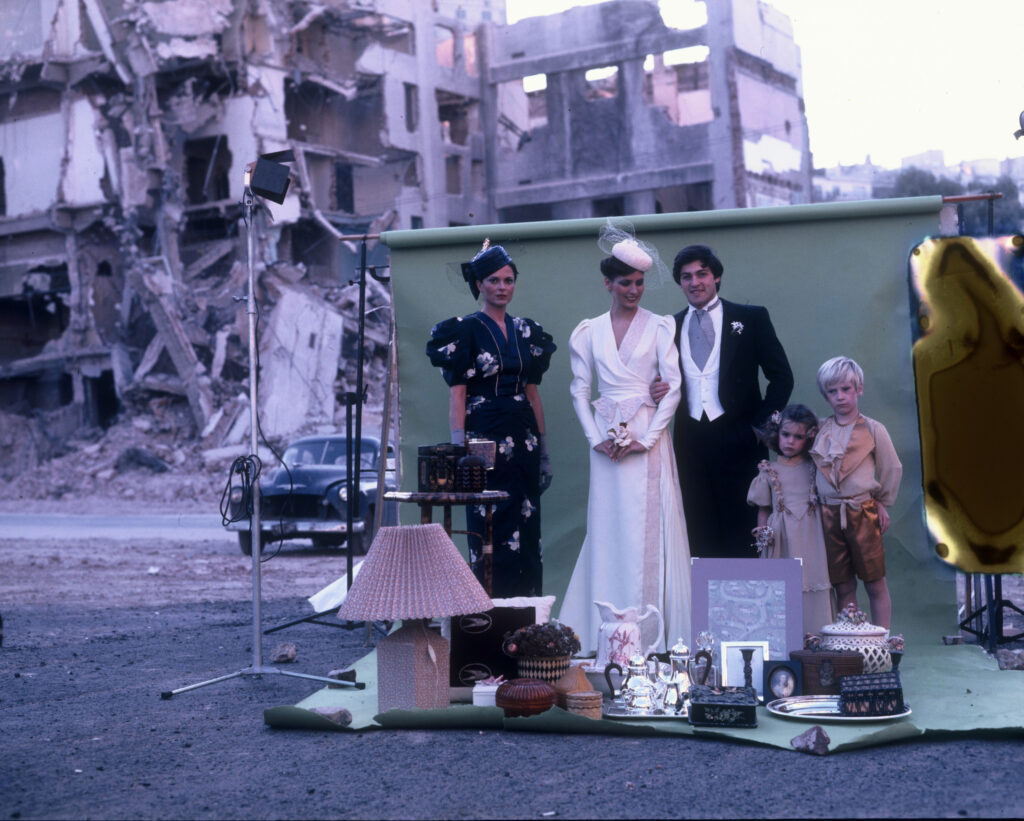

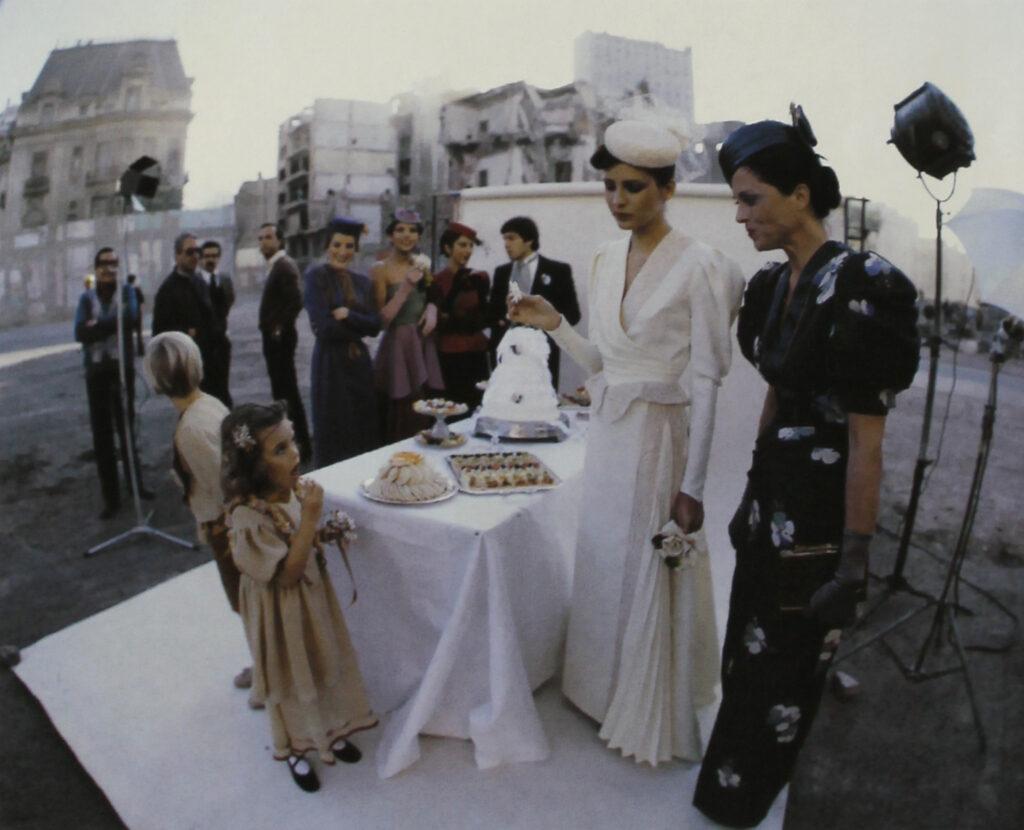

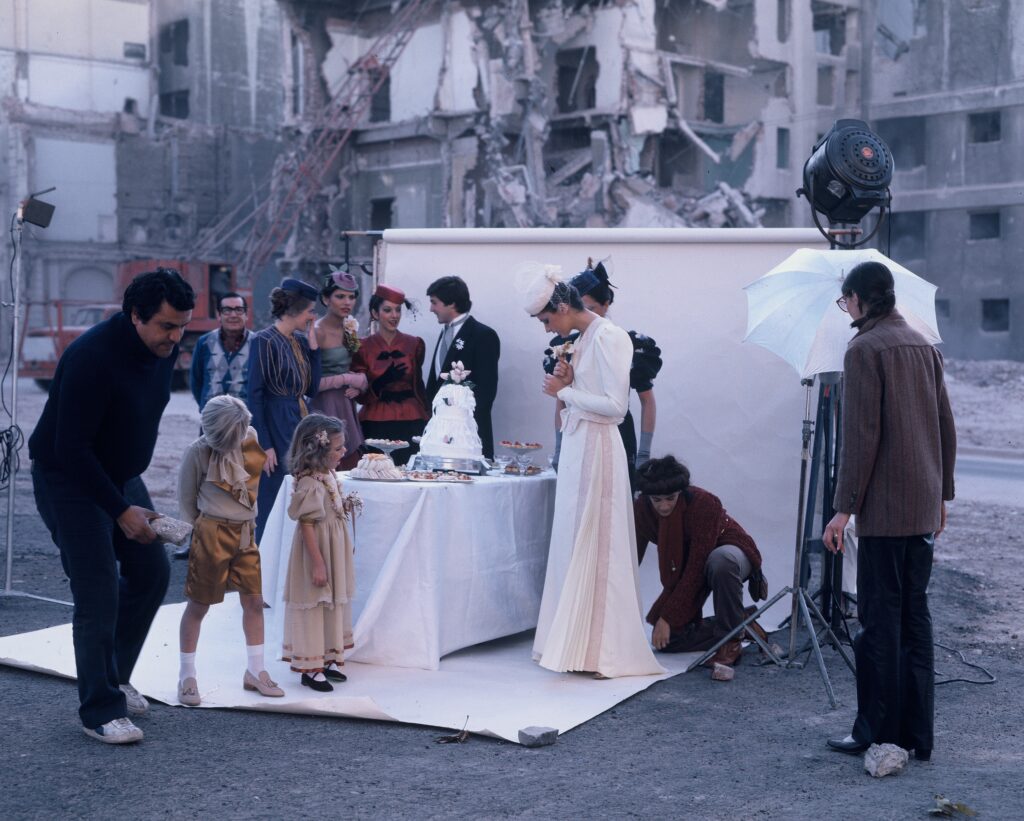

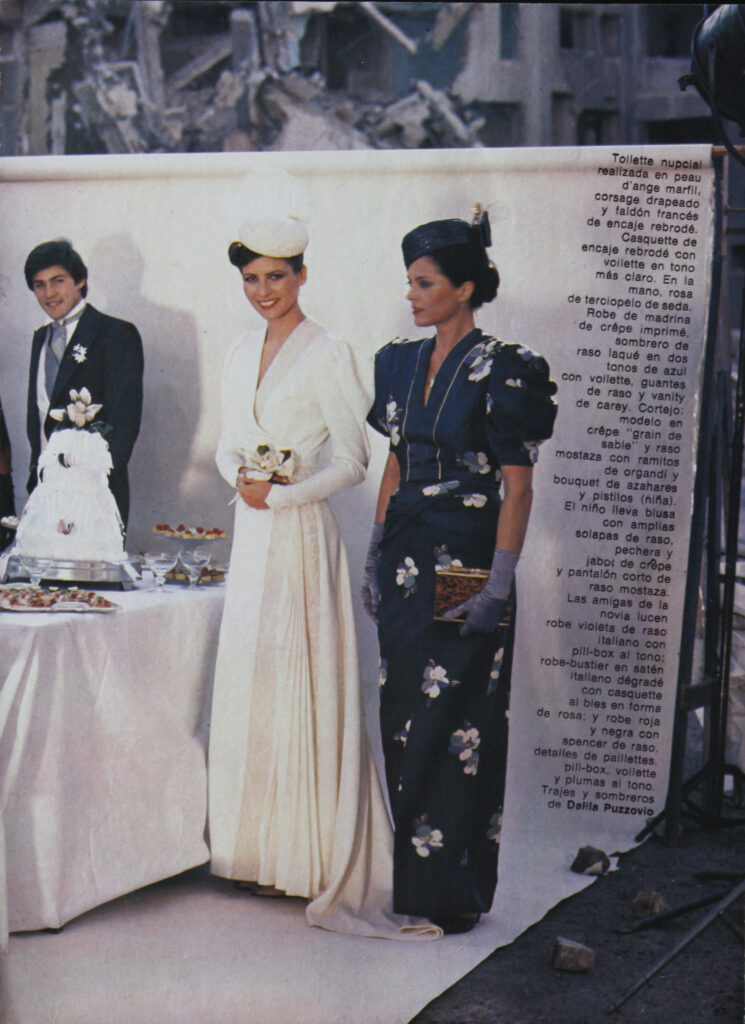

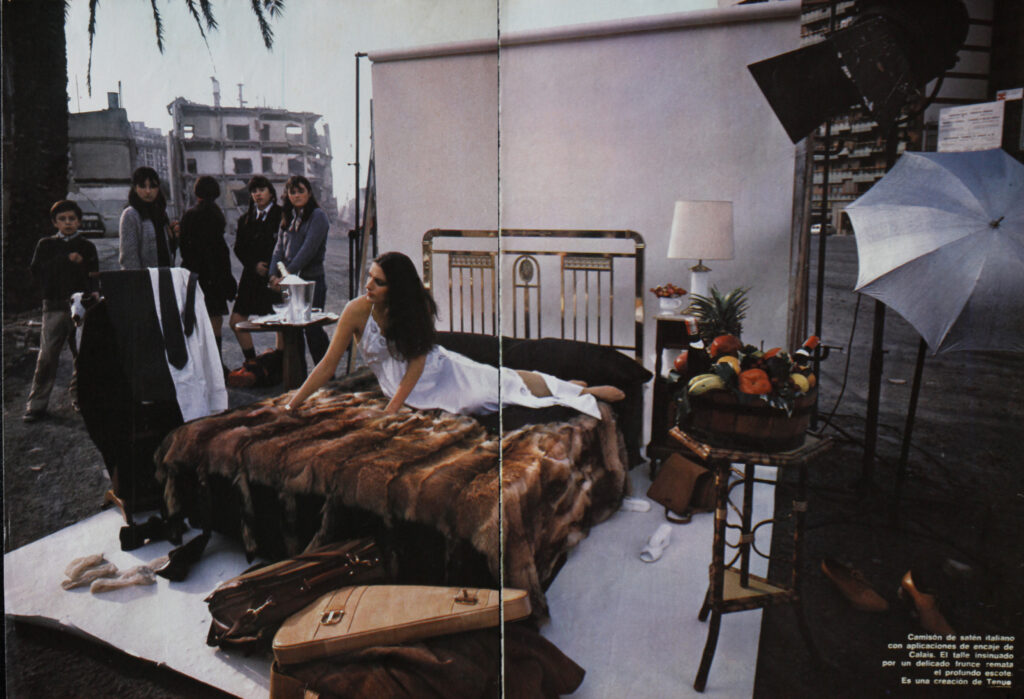

En 1979 Dalila Puzzovio realizó la producción fotográfica Mientras unos destruyen otros construyen para la revista Claudia. Considerada también una “acción performática”, se realizó durante la ampliación de la avenida 9 de Julio, en la que se destruyeron edificios históricos de la ciudad. En el registro fotográfico, puede verse la representación del casamiento de una pareja acompañada por sus testigos y cortejo, rodeada de un decorado de pompa, festín y regalos, con la ciudad en ruinas como telón de fondo.

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance en

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance en

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance en

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance en

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

De la serie Mientras unos construyen otros destruyen

Sin título

Año 1979

Fotografía por Margarita Dionisi Registro fotográfico de la performance en

Copias cromogénica sobre papel fotográfico

Colección de la artista

Dalila Puzzovio

No hay textos disponibles.

Museo Moderno

272 páginas

2025

Join our mailing list for

updates about our artists.

exhibitions, events and more.