“El cuartito empapelado tiene que ver con la casa de mis padres. Santa Fe. La textura emocional de mi juventud y de lo que soy como persona. Mi fotografía no habla de otra cosa que de la melancolía y de la ausencia. Traté de taparlo con el barroco carnavalesco del poplatino pero no lo logré. Pasan los años y cada vez me indentifico mas con los empapapelados floreados, con los retratos hechos en tiempo prolongado y luz de ventana…

Puedo decir que soy la textura de los tejidos de crochet que tejían mis tías. Soy las flores del empapelado. Los silencios. Los deseos reprimidos que muestan estas fotos. El resto, el colorinche, es puro cuento.”

Marcos López, junio 2015.

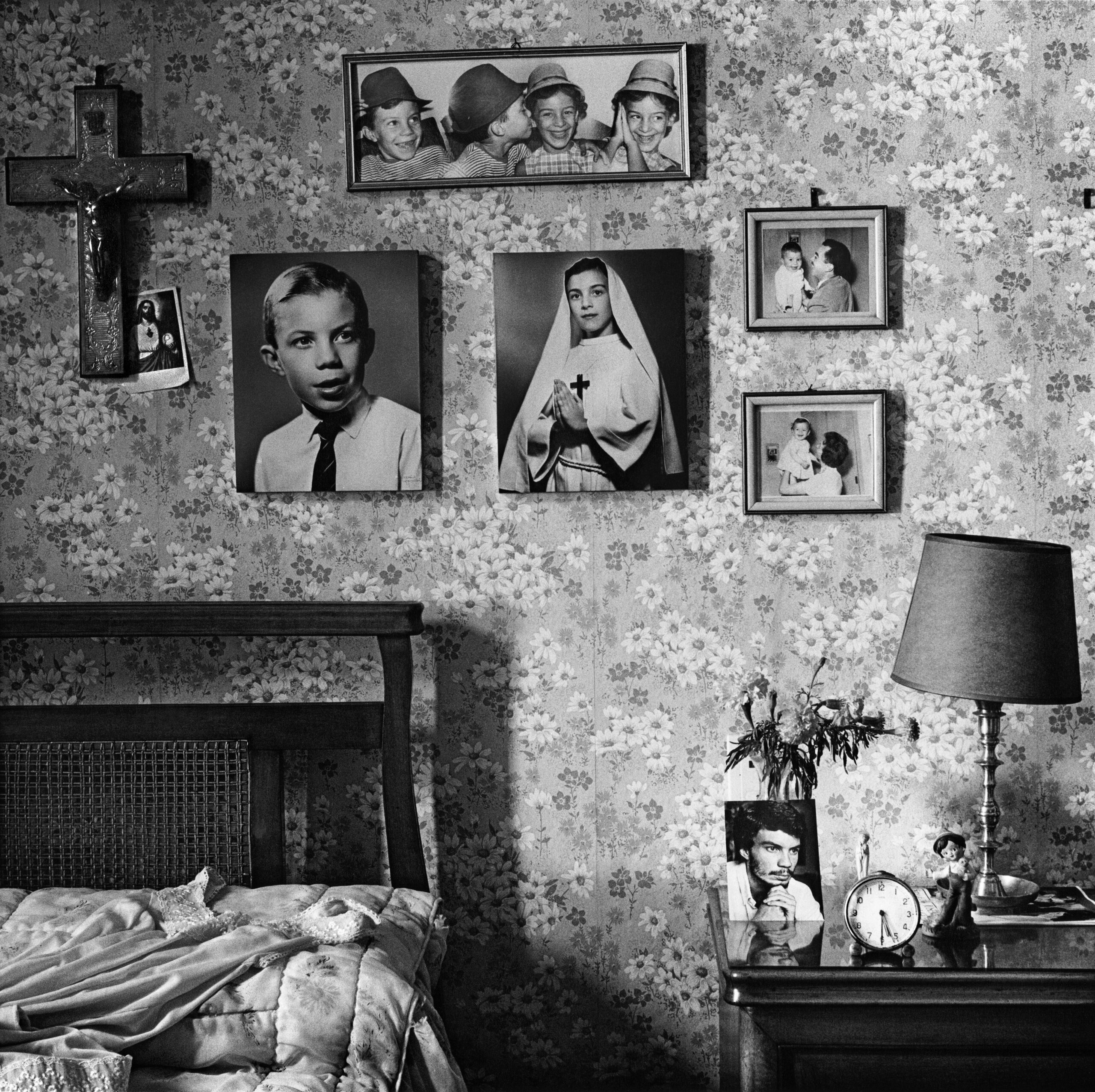

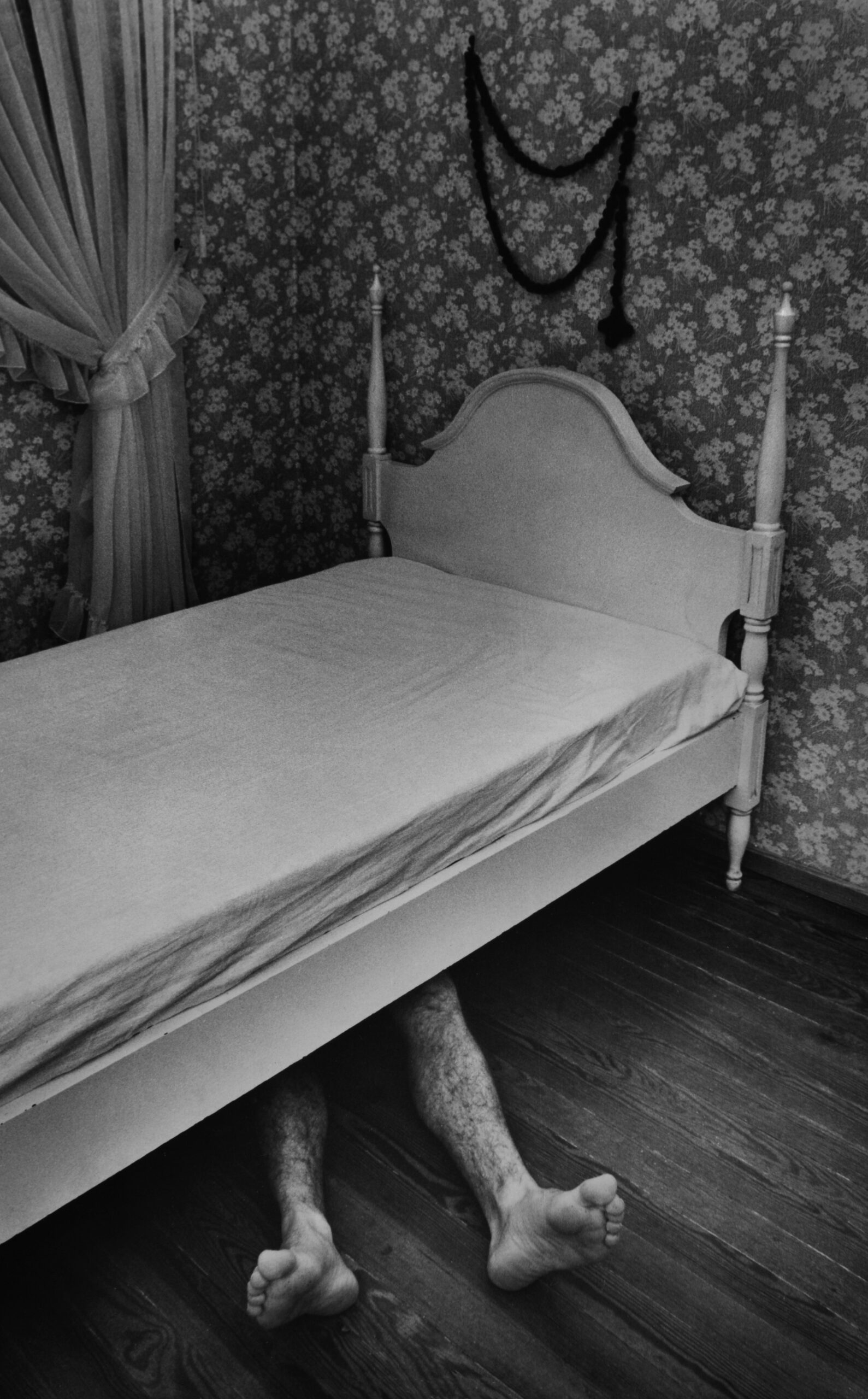

La vocación fotográfica de Marcos López surge a mediados de los ‘70, en el contexto de una vida provinciana, entre amigos, la familia, las calles grises de su ciudad santafesina, los clubes de barrio y los adornos de la casa, que luego han de convertirse en fuente de inspiración. Ese es el mundo que evocan las fotografías en blanco y negro realizadas entre 1982 y 1992, desde el distanciamiento provisto no tanto por el viaje a la capital como por la conciencia artística que éste implicaba. Dos de las imágenes más tempranas son “Autorretrato” y “Mi mamá” (1984). En ellas, López resume los valores que rigen la vida de una familia de clase media en la provincia, una mezcla de homenaje y de guiño humorístico. Es evidente la perspectiva kitsch de la mirada, pero también el tierno regodeo ante la acumulación de adornos y de símbolos que expresan el decoro y la moral cristiana del hogar. Cómplice de esa singular convivencia de humor y deferencia, la madre posa con absoluta seriedad frente al mundo de su gobierno, como ignorando la máscara que lleva puesta. “Nunca me preocupé por saber qué era el realismo mágico – dirá más tarde Marcos López – pero tal vez sea eso: cuando todas las partes de una situación son conscientes de participar de un acto absurdo teniendo respeto por no delatarlo”.

En el “Autorretrato” el artista aparece, pero no en persona, si no por medio de las fotos que adornan el cuarto materno. En medio del horror vacui doméstico, los retratos de los niños permiten citar, dentro de la imagen, el estilo característico de algún estudio fotográfico de barrio. Solo ese gesto bastaría para demostrar la conciencia estética desde la cual Marcos López va a elaborar, a lo largo de los años, su visión del valor local en la fotografía latinoamericana.

En blanco y negro coloca una sordina sobre el colorido decorado hogareño y en este disimulo coinciden las buenas formas de la imagen y de la vida social provinciana. Por supuesto, que entonces el color no era una posibilidad en el contexto de ese joven fotógrafo pero es cierto que ya aquí está presente el espíritu que el famoso Pop Latino iba a radicalizar.

En la obra de López la referencia al Arte Pop no alude tanto a la historia del arte como al proceso de degradación de las culturas locales en los márgenes del llamado “mundo global”. Sus fotografías aluden a una cultura periférica arrasada por el torrente homogeneizador del capitalismo tardío. Se percibe en las acumulaciones de objetos, en la teatralidad de los gestos, en las claves de color cargadas y disonantes. La latinidad de su propuesta busca entonces relativizar las pretensiones de toda estética regionalista en el panorama de devaluación actual de las culturas periféricas. Su obra implica un cuestionamiento a la fotografía de ejecución correcta, acento sentimental e iconografía autóctona que el sistema del arte internacional ha tipificado como paradigma de la producción latinoamericana.

Las alegorías documentales de Marcos López logran entonces una síntesis única entre el estilo “de los ‘90” y la herencia de la fotografía latinoamericana, en términos de un compromiso con la referencia a la realidad social. En su obra se sienten las reverberaciones de una larga tradición, que abarca desde el muralismo mexicano hasta la fotografía documental pasando por el retrato hasta inclusive el cine de protesta.

En su mas reciente producción sobre pósters de grandes maestros de la fotografía, como Ansel Adams, Marcos López a través de un gesto de apropiacionismo, yuxtapone citas fotográficas de artistas latinoamericanos, mal interpretadas, fuera de su oficio a través de la pintura, en un gesto que revela un sentimiento de amor y dolor, de pertenencia y rebeldía en un lenguaje visual donde convive el homenaje y el humor, dos recursos contrapuestos, que desafiándose mutuamente, distinguieron ayer estas imágenes del sentimentalismo de la fotografía regionalista, como los distinguen hoy de la frialdad intelectual de la ironía posmoderna.

Lorem ipsum sit dolor it amet

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1978

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

18 x 28 cm | 7 x 11 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1992

Fotografía. Díptico

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1992

Fotografía. Díptico

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1978

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

28 x 18 cm | 11 x 7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1992

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 30 cm | 15,7 x 11,8 in

Edición 10 + A/P

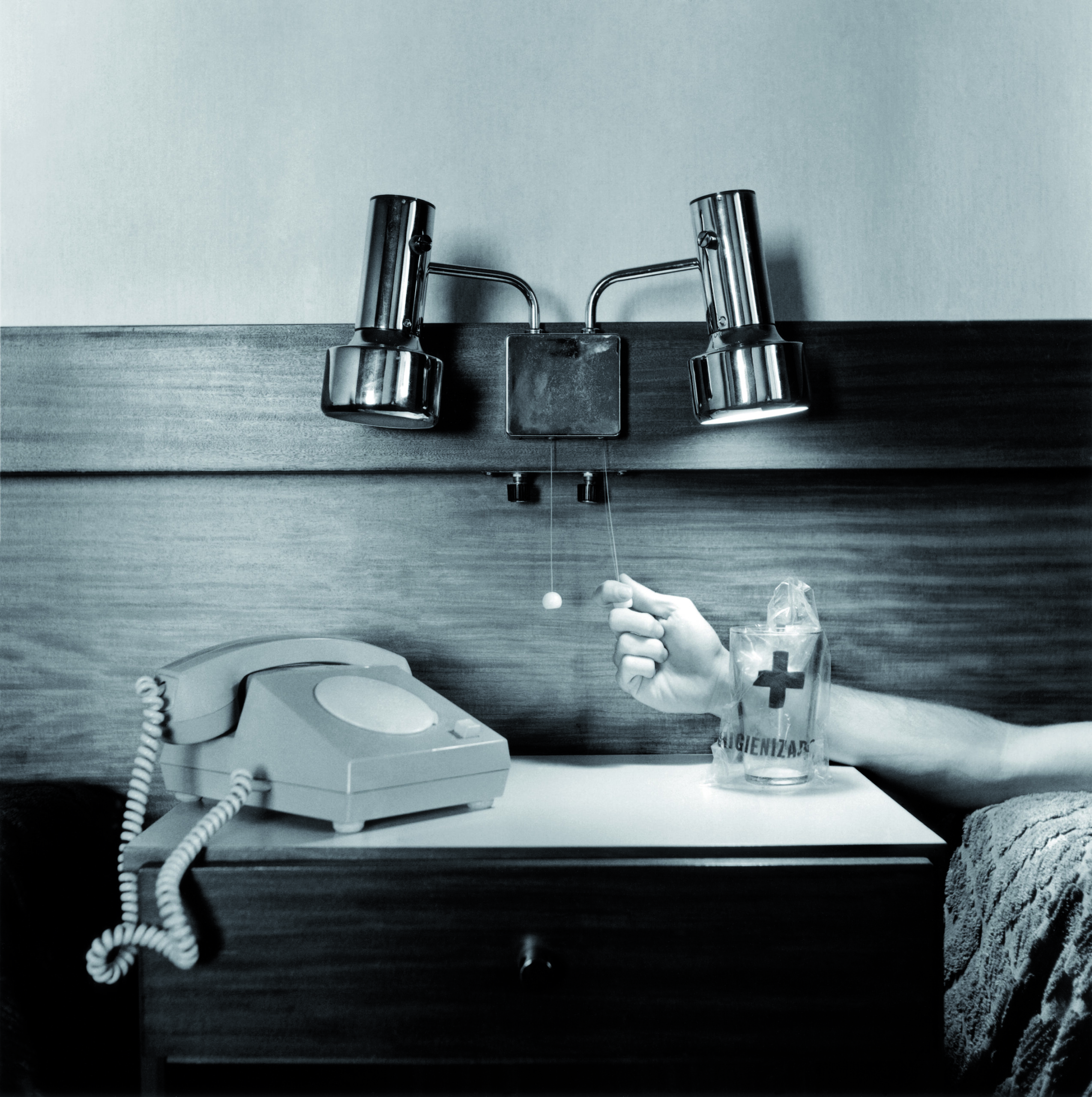

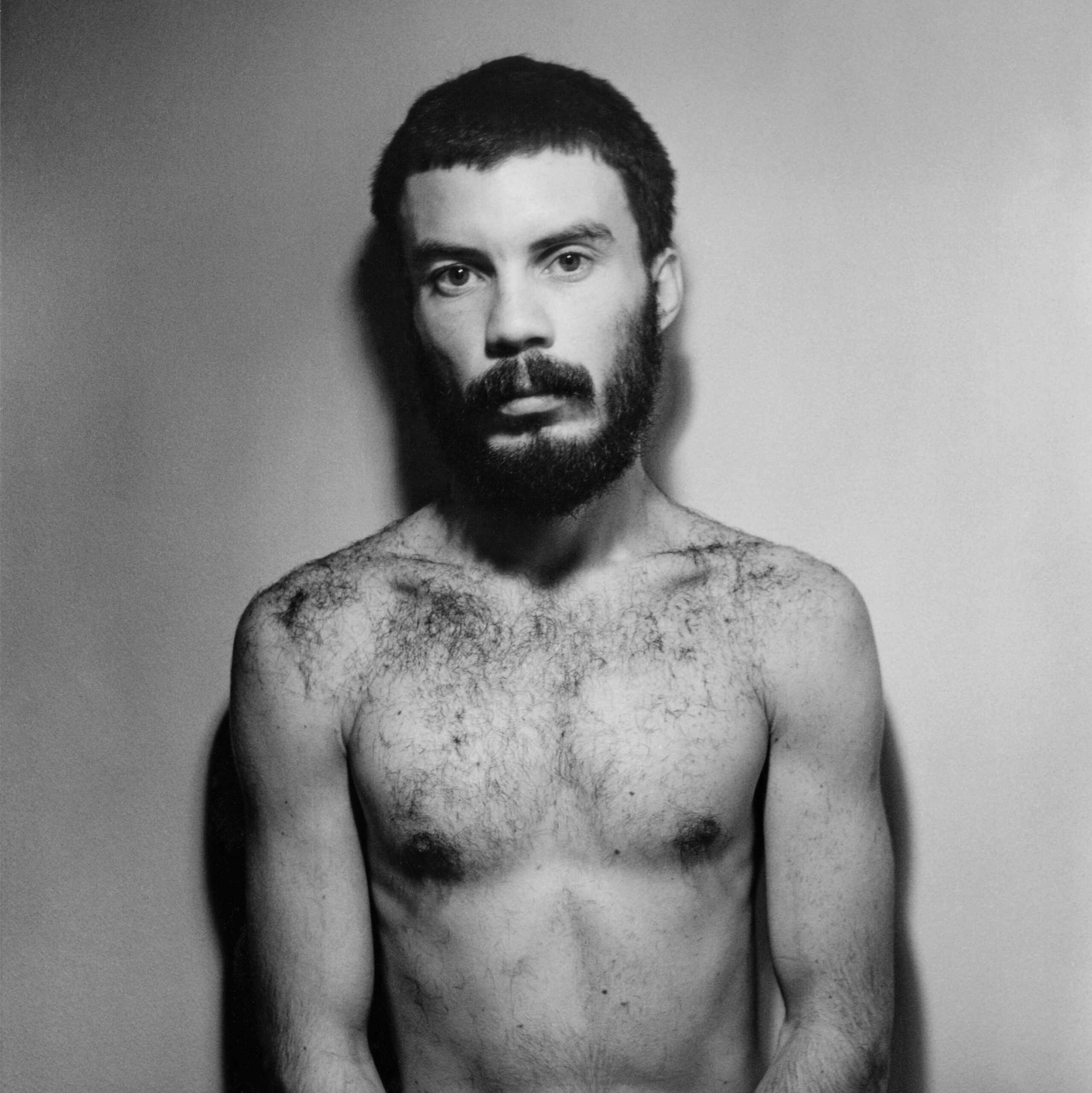

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1992

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

28 x 28 cm | 11 x 11 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1978

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

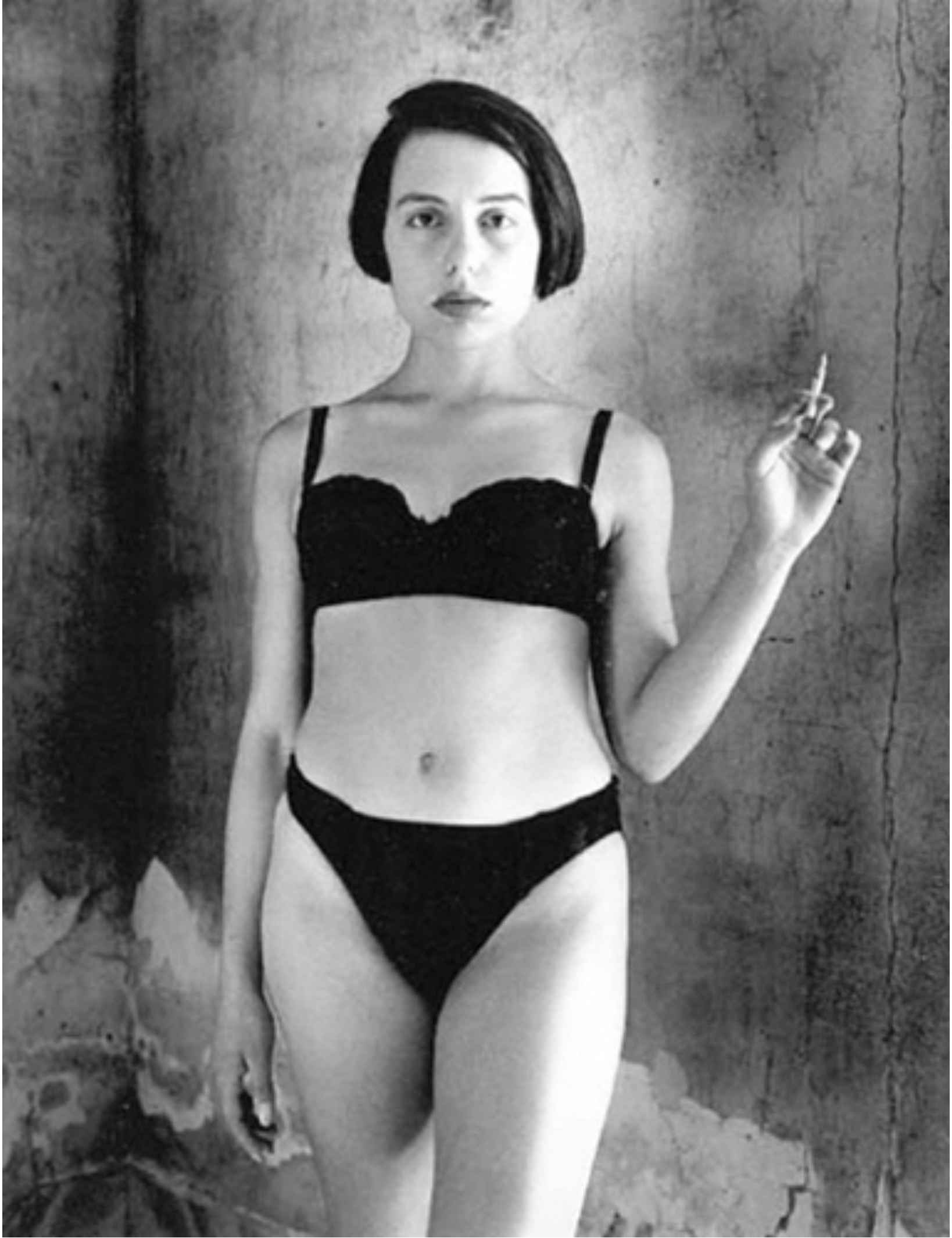

De la serie Blanco y negro

Doris, Santa Fe

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición | Edition 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año | Year 1992

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

20 x 20 cm | 7,9 x 7,9 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

20 x 20 cm | 7,9 x 7,9 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1992

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

20 x 20 cm | 7,9 x 7,9 in

Edición 10 + A/P

De la serie Blanco y negro

Año 1984

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

40 x 40 cm | 15,7 x 15,7 in

Edición 10 + A/P

“El cuartito empapelado tiene que ver con la casa de mis padres. Santa Fe. La textura emocional de mi juventud y de lo que soy como persona. Mi fotografía no habla de otra cosa que de la melancolía y de la ausencia. Traté de taparlo con el barroco carnavalesco del poplatino pero no lo logré. Pasan los años y cada vez me indentifico mas con los empapapelados floreados, con los retratos hechos en tiempo prolongado y luz de ventana…

Puedo decir que soy la textura de los tejidos de crochet que tejían mis tías. Soy las flores del empapelado. Los silencios. Los deseos reprimidos que muestan estas fotos. El resto, el colorinche, es puro cuento.”

Marcos López, junio 2015.

La vocación fotográfica de Marcos López surge a mediados de los ‘70, en el contexto de una vida provinciana, entre amigos, la familia, las calles grises de su ciudad santafesina, los clubes de barrio y los adornos de la casa, que luego han de convertirse en fuente de inspiración. Ese es el mundo que evocan las fotografías en blanco y negro realizadas entre 1982 y 1992, desde el distanciamiento provisto no tanto por el viaje a la capital como por la conciencia artística que éste implicaba. Dos de las imágenes más tempranas son “Autorretrato” y “Mi mamá” (1984). En ellas, López resume los valores que rigen la vida de una familia de clase media en la provincia, una mezcla de homenaje y de guiño humorístico. Es evidente la perspectiva kitsch de la mirada, pero también el tierno regodeo ante la acumulación de adornos y de símbolos que expresan el decoro y la moral cristiana del hogar. Cómplice de esa singular convivencia de humor y deferencia, la madre posa con absoluta seriedad frente al mundo de su gobierno, como ignorando la máscara que lleva puesta. “Nunca me preocupé por saber qué era el realismo mágico – dirá más tarde Marcos López – pero tal vez sea eso: cuando todas las partes de una situación son conscientes de participar de un acto absurdo teniendo respeto por no delatarlo”.

En el “Autorretrato” el artista aparece, pero no en persona, si no por medio de las fotos que adornan el cuarto materno. En medio del horror vacui doméstico, los retratos de los niños permiten citar, dentro de la imagen, el estilo característico de algún estudio fotográfico de barrio. Solo ese gesto bastaría para demostrar la conciencia estética desde la cual Marcos López va a elaborar, a lo largo de los años, su visión del valor local en la fotografía latinoamericana.

En blanco y negro coloca una sordina sobre el colorido decorado hogareño y en este disimulo coinciden las buenas formas de la imagen y de la vida social provinciana. Por supuesto, que entonces el color no era una posibilidad en el contexto de ese joven fotógrafo pero es cierto que ya aquí está presente el espíritu que el famoso Pop Latino iba a radicalizar.

En la obra de López la referencia al Arte Pop no alude tanto a la historia del arte como al proceso de degradación de las culturas locales en los márgenes del llamado “mundo global”. Sus fotografías aluden a una cultura periférica arrasada por el torrente homogeneizador del capitalismo tardío. Se percibe en las acumulaciones de objetos, en la teatralidad de los gestos, en las claves de color cargadas y disonantes. La latinidad de su propuesta busca entonces relativizar las pretensiones de toda estética regionalista en el panorama de devaluación actual de las culturas periféricas. Su obra implica un cuestionamiento a la fotografía de ejecución correcta, acento sentimental e iconografía autóctona que el sistema del arte internacional ha tipificado como paradigma de la producción latinoamericana.

Las alegorías documentales de Marcos López logran entonces una síntesis única entre el estilo “de los ‘90” y la herencia de la fotografía latinoamericana, en términos de un compromiso con la referencia a la realidad social. En su obra se sienten las reverberaciones de una larga tradición, que abarca desde el muralismo mexicano hasta la fotografía documental pasando por el retrato hasta inclusive el cine de protesta.

En su mas reciente producción sobre pósters de grandes maestros de la fotografía, como Ansel Adams, Marcos López a través de un gesto de apropiacionismo, yuxtapone citas fotográficas de artistas latinoamericanos, mal interpretadas, fuera de su oficio a través de la pintura, en un gesto que revela un sentimiento de amor y dolor, de pertenencia y rebeldía en un lenguaje visual donde convive el homenaje y el humor, dos recursos contrapuestos, que desafiándose mutuamente, distinguieron ayer estas imágenes del sentimentalismo de la fotografía regionalista, como los distinguen hoy de la frialdad intelectual de la ironía posmoderna.

Valeria González (extracto de texto del libro Marcos López, Ediciones Larrivière, año 2010)

No hay publicaciones de prensa disponibles.

La vocación fotográfica de Marcos López surge a mediados de los ‘70, en el contexto de una vida provinciana, entre amigos, la familia, las calles grises de su ciudad santafesina, los clubes de barrio y los adornos de la casa, que luego han de convertirse en fuente de inspiración. Ese es el mundo que evocan las fotografías en blanco y negro realizadas entre 1982 y 1992, desde el distanciamiento provisto no tanto por el viaje a la capital como por la conciencia artística que éste implicaba. Dos de las imágenes más tempranas son “Autorretrato” y “Mi mamá” (1984). En ellas, López resume los valores que rigen la vida de una familia de clase media en la provincia, una mezcla de homenaje y de guiño humorístico. Es evidente la perspectiva kitsch de la mirada, pero también el tierno regodeo ante la acumulación de adornos y de símbolos que expresan el decoro y la moral cristiana del hogar. Cómplice de esa singular convivencia de humor y deferencia, la madre posa con absoluta seriedad frente al mundo de su gobierno, como ignorando la máscara que lleva puesta. “Nunca me preocupé por saber qué era el realismo mágico – dirá más tarde Marcos López – pero tal vez sea eso: cuando todas las partes de una situación son conscientes de participar de un acto absurdo teniendo respeto por no delatarlo”.

En el “Autorretrato” el artista aparece, pero no en persona, si no por medio de las fotos que adornan el cuarto materno. En medio del horror vacui doméstico, los retratos de los niños permiten citar, dentro de la imagen, el estilo característico de algún estudio fotográfico de barrio. Solo ese gesto bastaría para demostrar la conciencia estética desde la cual Marcos López va a elaborar, a lo largo de los años, su visión del valor local en la fotografía latinoamericana.

En blanco y negro coloca una sordina sobre el colorido decorado hogareño y en este disimulo coinciden las buenas formas de la imagen y de la vida social provinciana. Por supuesto, que entonces el color no era una posibilidad en el contexto de ese joven fotógrafo pero es cierto que ya aquí está presente el espíritu que el famoso Pop Latino iba a radicalizar.

En la obra de López la referencia al Arte Pop no alude tanto a la historia del arte como al proceso de degradación de las culturas locales en los márgenes del llamado “mundo global”. Sus fotografías aluden a una cultura periférica arrasada por el torrente homogeneizador del capitalismo tardío. Se percibe en las acumulaciones de objetos, en la teatralidad de los gestos, en las claves de color cargadas y disonantes. La latinidad de su propuesta busca entonces relativizar las pretensiones de toda estética regionalista en el panorama de devaluación actual de las culturas periféricas. Su obra implica un cuestionamiento a la fotografía de ejecución correcta, acento sentimental e iconografía autóctona que el sistema del arte internacional ha tipificado como paradigma de la producción latinoamericana.

Las alegorías documentales de Marcos López logran entonces una síntesis única entre el estilo “de los ‘90” y la herencia de la fotografía latinoamericana, en términos de un compromiso con la referencia a la realidad social. En su obra se sienten las reverberaciones de una larga tradición, que abarca desde el muralismo mexicano hasta la fotografía documental pasando por el retrato hasta inclusive el cine de protesta.

En su mas reciente producción sobre pósters de grandes maestros de la fotografía, como Ansel Adams, Marcos López a través de un gesto de apropiacionismo, yuxtapone citas fotográficas de artistas latinoamericanos, mal interpretadas, fuera de su oficio a través de la pintura, en un gesto que revela un sentimiento de amor y dolor, de pertenencia y rebeldía en un lenguaje visual donde convive el homenaje y el humor, dos recursos contrapuestos, que desafiándose mutuamente, distinguieron ayer estas imágenes del sentimentalismo de la fotografía regionalista, como los distinguen hoy de la frialdad intelectual de la ironía posmoderna.

Join our mailing list for

updates about our artists.

exhibitions, events and more.