Roberto Huarcaya (1959, Peru) es uno de los artistas contemporáneos más distinguidos y comprometidos del Perú. Desde su aparición en la escena de las artes visuales, destacó por la ambición de sus proyectos, en los que a menudo el medio fotográfico se ha visto unido a otros medios de creación en combinaciones de gran solvencia.

A Huarcaya siempre le ha interesado lo real como espacio de creación. Sus propuestas con frecuencia han girado potentemente en torno a la construcción de la identidad individual y colectiva de cara a situaciones que van desde lo banal-cotidiano, pasando por lo erótico como punto de inflexión de la libertad, hasta alcanzar el plano político. Ejerciendo una mirada antropológica sobre las imágenes que elige tomar, el artista combina su interés por la naturaleza con sus bosques, océanos y selvas los cuales se manifiestan en series emblemáticas tales como “Amazogramas” (2014). También el ámbito rural, costumbres, bailes y niños son abordados en “Danzas Andinas” (2018) y “Andegramas” (2017). Su trabajo se ha lanzado a perseguir estos proyectos con dispositivos visuales que transformaran su lectura, cuestionando lo fotográfico pero sin violentar el soporte mismo de la imagen, sino más bien permitiendo una experiencia abierta y critica hacia la configuración de la misma. No hay límites territoriales para la indagación creativa del artista porque no hay límites en su compromiso por penetrar intelectual y físicamente en cada uno de esos territorios para lograr mediante su propia experimentación sensible, traducirlo en imágenes que recuperan de la historia de la fotografía, procedimientos primigenios, paradójicamente innovadores para la fotografía actual. Desde el 2014, el artista ha dirigido su atención a la fotografía sin cámara y está produciendo ‘fotogramas’, regresando a los orígenes mismos de la fotografía y utilizando una técnica primitiva para capturar realidades primigenias. A través de estas obras de material fotosensible de dimensiones monumentales, con una mezcla de intuición y resonancia, Huarcaya nos permite re-anudar la sensibilidad, que es como un palimpsesto de nuestra historia personal, a una dinámica sensorial agitada, en la cámara de la consciencia.

Roberto Huarcaya (1959, Perú) is one of the most distinguished and committed contemporary artists in Peru. Since his appearance on the visual arts scene, he stood out for the ambition of his projects, in which the photographic medium has often been linked to other creative means in combinations of great solvency. Huarcaya has always been interested in reality as a space for creation

Huarcaya has always been interested in reality as a space for creation. His proposals have frequently powerfully revolved around the construction of individual and collective identity facing situations that range from the banal everyday, going through the erotic as a turning point of freedom, to reaching the political plane. Exercising an anthropological point of view on the images he chooses to take, the artist combines his interest in nature with its forests, oceans and jungles, which are manifested in emblematic series such as “Amazogramas” (2014). Also the rural environment, customs, dances and children are addressed in “Danzas Andinas” (2018) and “Andegramas” (2017). His work aimed to pursue these projects with visual devices that transform their reading, questioning the photographic but without violating the support of the image itself, but rather allowing an open and critical experience towards its configuration. There are no territorial limits for the creative investigation of the artist because there are no limits in his commitment to penetrate intellectually and physically into each of those territories to achieve, through his own sensitive experimentation, translate it into images that recover from the history of photography, primal procedures, paradoxically innovative for today’s photography. Since 2014, the artist has turned his attention to photography without camera and is producing ‘photograms’, returning to the very origins of photography and using a primitive technique to capture primeval realities. Through these works of photosensitive material of monumental dimensions, with a mixture of intuition and resonance, Huarcaya allows us to re-tie the sensitivity, which is like a palimpsest of our personal history, to a hectic sensory dynamics, in the chamber of the consciousness.

Roberto Huarcaya (Lima, Perú | b.1959) se graduó en Psicología en la Universidad Católica del Perú, estudio Cine en el Instituto Italiano de Cultura y Fotografía en el Centro del Video y la Imagen (Madrid, 1989), año en que comienza a dedicarse a la fotografía. Es profesor de Fotografía en la Universidad de Lima (1990-1993), en el Instituto Gaudí (Lima, 1993-1997) y en el Centro de la Fotografía, ahora Centro de la Imagen de Lima, desde 1999 y del cual fue fundador y director hasta julio de 2022.

Participa en la 6ta Bienal de La Habana (Cuba, 1997), Bienal de Lima (Perú, 1997, 1998 y 2000); Primavera Fotográfica de Cataluña en 1998; PhotoEspaña 1999; 49o Bienal de Venecia (Italia, 2001); Polyptychs en el CoCA Center on Contemporary Art de Seattle (EE UU, 2007); Dialogues en el MOLAA, Museum of Latin American Art de California (EE UU, 2009); Mois de la Photo 2010 en París (Francia); Bienal de Fotografía de Daegu (Corea del Sur, 2014); Pabellón peruano de la Bienal de Arquitectura de Venecia (Italia, 2016), donde reciben mención especial como Pabellón nacional; Arco Lisboa Portugal, 2017; ArteBa Focus Buenos Aires, Argentina 2017; ARCO 2019 en la selección oficial de Perú país invitado; Buenos Aires Photo 2019; Festival de Fotografía en Noorderlicht Photo en Países Bajos; Paris Photo 2019; Zona Maco México 2020 con un solo show; Cien del MUAC, México, 2021; Festival de Vannes 2022, Francia; The Armory Show 2022, Nueva York; Off Screen, París, 2022; Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now en el Eskenazi Museum of Art en Indiana, USA, 2023; Festival Sans Frontière, Francia, 2023; Pinta Parc, Lima, 2023; Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles 2023; Paris Photo 2023; Amazonia: A biocreativity Hub, IDB Cultural Center Washington DC, 2024. Fue elegido en el Concurso curatorial para representar al Perú en la Bienal de Arte de Venecia 2024. Participa en Photo London 2024; Donggang International Photo, Corea del Sur, 2024; ArteBa 2024; El dorado, en Museo Amparo, Puebla, México; Paris Photo 2024 y Art Basel Miami 2024 con la galería Rolf Art. Sus exposiciones individuales son: Deseos, Temores y Divanes (Lima, 1990); Fotografías (Lima, 1992); Continuum (Lima, 1994); La Nave del Olvido (Lima, 1996, París, 1997 y Barcelona, 1998); Temps Rêvés (París, 1998); Ciudad Luz (Lima, 2000); Devenir (Guayaquil, 2003 y Santiago, 2004); El Último Viaje (Buenos Aires, 2004); Antológica (Lima, 2004); Entre Tiempos (Lima, 2005); Ambulantes (Londres, 2007); Obra reciente (Miami y Lima, 2011); Sutil Violento (Lisboa, 2011); Amazogramas (Lima, 2014; Dina Mitrani Gallery Miami, 2015; Festival Internacional Valongo, Sao Paulo, Brasil, 2016; Galería Parque Rodó en Montevideo, Uruguay, 2016); Amazonía (Galería Rolf Art, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018); Amazogramas (Art Museum of the Americas – AMA, Washington, Estados Unidos, 2018-2019); Amazonía (Casa de América, Barcelona, España, 2019); Cuerpos develados (Galería El Ojo Ajeno, Lima, 2021); Océanos (Penumbra Foundation, Nueva York, 2022); Ver por contacto. Fotogramas 2014-2024 en el Espacio Germán Krüger del ICPNA de Miraflores, Lima. Su obra forma parte de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie en París; Fine Arts Museum of Houston; MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art de California; CoCA Center on Contemporary Art de Seattle; Lehigh University Art Collection; MUAC-UNAM en México; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima; Museo de San Marcos en Lima; Fundación América en Santiago de Chile; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wilfredo Lam de La Habana; Fototeca Latinoamericana FOLA de Buenos Aires; Colección Hochschild; Colección Jan Mulder, Colección La Riviere; Colección Quattrini, entre otras. Ha participado como conferencista, profesor y revisor de portafolios invitado en los Talleres Nacionales de Chile, Santiago 2014 y Valparaíso 2015; PhotoEspaña 2009, 2011 en México y Guatemala; Forum Latinoamericano de Fotografía de Sao Paulo en 2007, 2010, 2013 y 2016; Encuentros Abiertos de Fotografía de Buenos Aires, Argentina en 2002, 2004, 2006 y 2008; Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía en Almería, España en 2008; École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie d’Arles, Francia en 2005, 2006, 2007, 2010 y 2012; Foto América Chile 2006; FotoFest 2002; entre otros. Fue codirector de la Bienal de Fotografía de Lima (2012-2014) y de Lima Photo (2010-2019), feria especializada en galerías de fotografía. Fue coeditor de la revista CDI del Centro de la Imagen y de Sueño de la Razón, revista latinoamericana de fotografía.

Roberto Huarcaya (Lima, Perú | b.1959) graduated in Psychology at the Universidad Católica del Perú (Lima, 1978-1984). Studied Cinema at the Instituto Italiano de Cultura (Lima, 1982) and Photography at the Centro del Video y la Imagen (Madrid, 1989), year in which he focused on photography. He taught Photography at the Universidad de Lima (1990-1993), at the Gaudi Institute (Lima, 1993-1997) and at the Centro de la Fotografía, now Centro de la Imagen (Lima, since 1999) of which he was founder and director until July 2022.

Participated in the 6th Havana Biennial (Cuba, 1997); Lima Biennial (Peru 1997, 1998 and 2000); Primavera Fotográfica of Cataluña 1998 (Spain); PhotoEspaña 1999 (Spain); 49th Venice Biennale, 2001 (Italy); in Polyptychs at CoCA Center on Contemporary Art, Seattle, 2007 (USA); Dialogues at MOLAA, Museum of Latin American Art California in 2009 (USA); Mois de la Photo 2010 (Paris, France); Daegu Photo Biennale (South Korea, 2014); Peruvian pavilion of the Venice Biennale of Architecture (Italy, 2016), awarded with special mention as National Pavilion; Arco Lisboa Portugal, 2017; ArteBa Focus Buenos Aires, Argentina 2017; ARCO 2019 in the official selection of Peru guest country; Buenos Aires Photo 2019; Noorderlicht Photo Festival in The Netherlands; Paris Photo 2019; Zona Maco Mexico 2020 with a solo show; Cien del MUAC, Mexico, 2021; Vannes Festival 2022, France; The Armory Show 2022, New York; Off Screen, Paris, 2022; Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana, USA, 2023; Festival Sans Frontière, France, 2023; Pinta Parc, Lima, 2023; Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles, France, 2023; Paris Photo 2023; Amazonia: A biocreativity Hub, IDB Cultural Center Washington DC, 2024. It has been chosen in the Curatorial Competition to represent Peru at the Biennale di Venezia 2024; Photo London 2024; Donggang International Photo, South Korea, 2024; ArteBa 2024; El dorado exhibition, Museo Amparo, Puebla, Mexico; Paris Photo 2024 and Art Basel Miami 2024 with Rolf Art. Solo exhibitions: Deseos, Temores y Divanes (Lima, 1990), Fotografías (Lima, 1992), Continuum (Lima, 1994), La Nave del Olvido (Lima, 1996, Paris, 1997 and Barcelone, 1998), Temps Rêvés (Paris, 1998), Ciudad Luz (Lima, 2000), Devenir (Guayaquil, 2003 and Santiago, 2004), El Último Viaje (Buenos Aires, 2004), Antológica (Lima, 2004), Entre Tiempos (Lima, 2005), Ambulantes (London, 2007), Obra reciente (Miami and Lima, 2011), Sutil Violento (Lisbon, 2011); Amazogramas (Lima, 2014; Dina Mitrani Gallery Miami, 2015; Festival Internacional Valongo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2016; Galería Parque Rodó en Montevideo, Uruguay, 2016); Amazonía (Galería Rolf Art, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018); Amazogramas (Art Museum of the Americas – AMA, Washington, USA, 2018-2019); Amazonía (Casa de América, Barcelona, España, 2019); Cuerpos develados (Galería El Ojo Ajeno, Lima, 2021); Océanos (Penumbra foundation, New York, 2022); Ver por contacto. Fotogramas 2014-2024, at the Germán Krüger gallery of the ICPNA in Miraflores, Lima, 2024. His work is part of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie of Paris; Fine Arts Museum of Houston; MOLAA Museum of Latin American Art of California; COCA Center on Contemporary Art, in Seattle; Lehigh University Art Collection; MUAC-UNAM Mexico; MALI – Museo de Arte de Lima; Museo de San Marcos, Lima; Fundación América in Santiago, Chile; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wilfredo Lam, Havana, Cuba; Fototeca Latinoamericana FOLA Buenos Aires, Argentina; Hochschild Collection; Jan Mulder Collection; La Riviere Collection; Quattrini Collection and other private collections. He has been invited as speaker, teacher and portfolio reviewer at Talleres Nacionales de Chile, Santiago 2014 and Valparaíso 2015; PhotoEspaña 2009, 2011 in Mexico and Guatemala; Forum Latinoamericano de Fotografía in Sao Paulo, Brazil 2007, 2010, 2013 and 2016; Encuentros Abiertos de Fotografía Buenos Aires, Argentina 2002, 2004, 2006 y 2008; Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía Almería, Spain, 2008; École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie d’Arles, France in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2010 and 2012; Foto América Chile 2006; FotoFest 2002, USA.Huarcaya was co-director of the Bienal de Fotografía de Lima (2012-2014) and Lima Photo (2010-2019), editor of Peruvian magazine CDI and editor from Peru of Sueño de la Razón, a Latin American review.

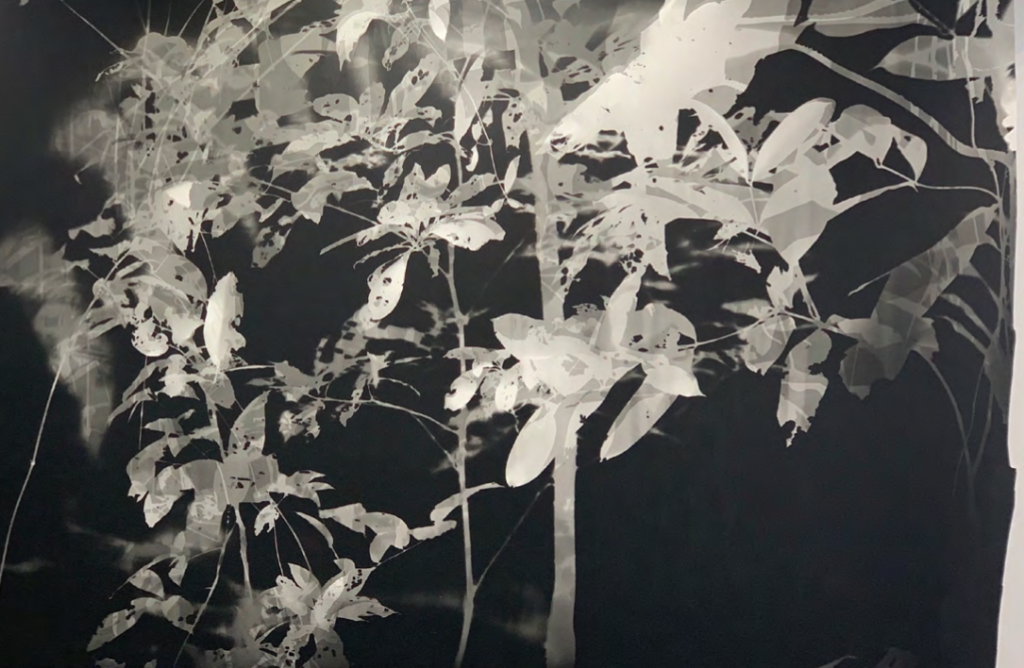

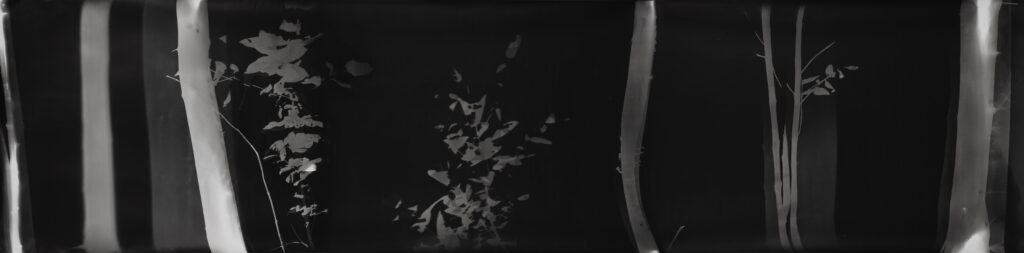

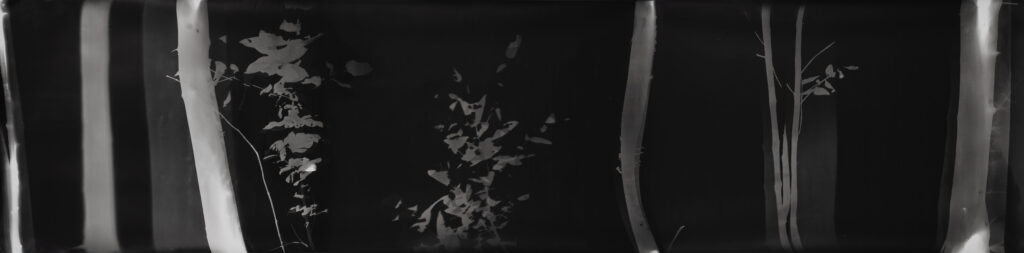

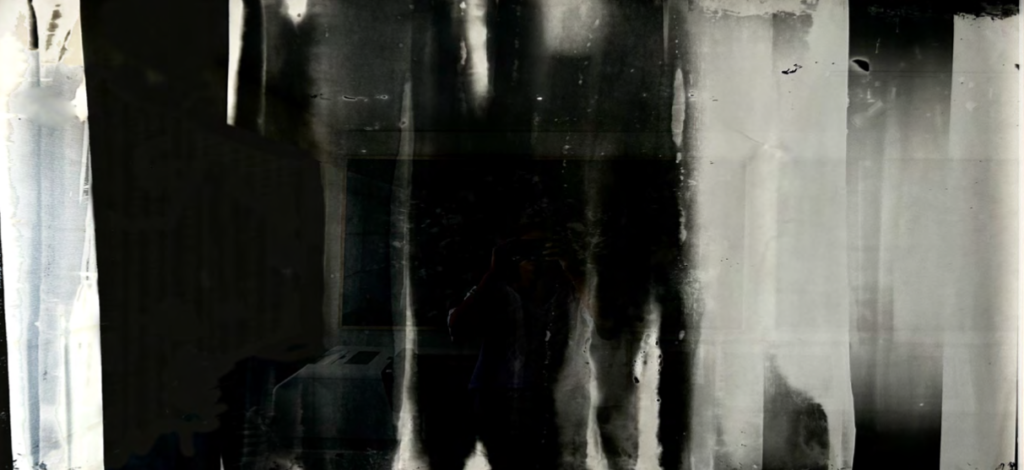

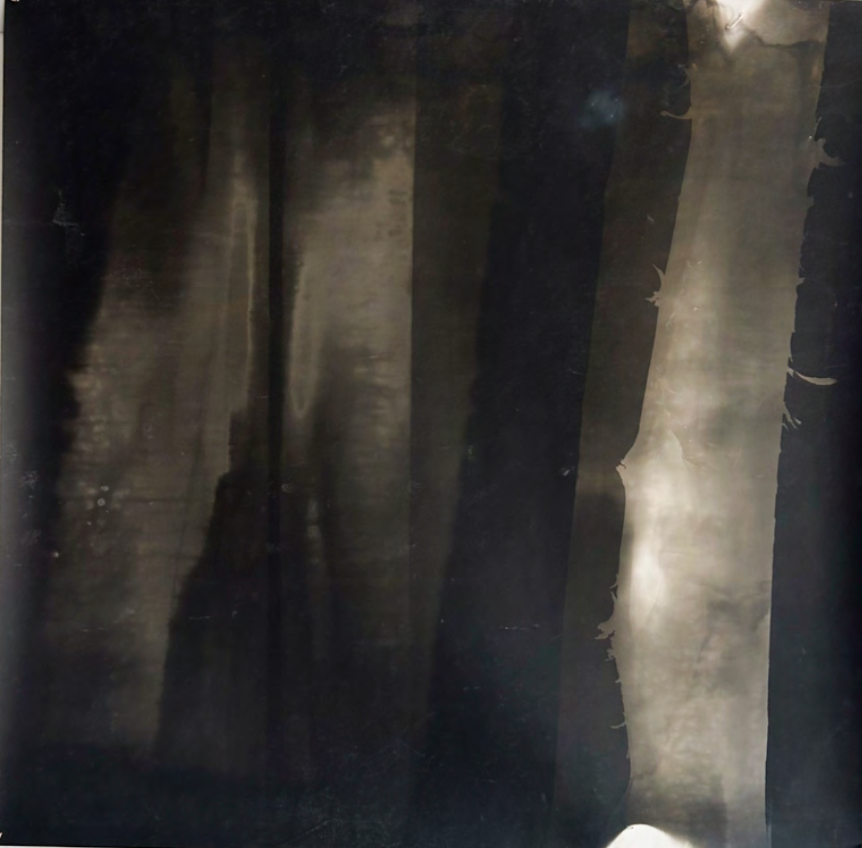

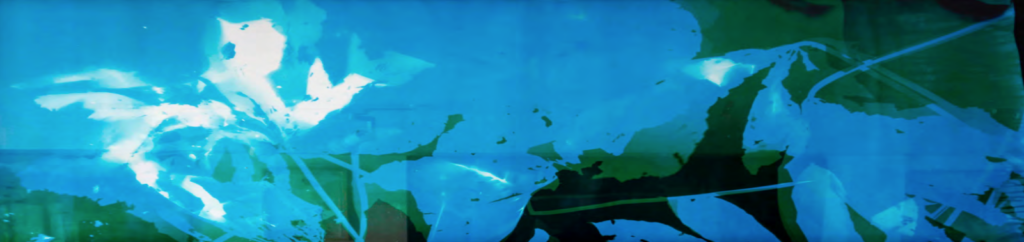

Roberto Huarcaya concibió Amazogramas (2014-2024), una serie de fotogramas de gran escala de la selva peruana, invitado en 2014 por la organización ecologista WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society) a Bahuaja Sonene, una Reserva Natural Intangible en la selva amazónica al suroeste de Perú. Desplegando papel fotosensible en la densa selva, de noche bajo la luz de la luna llena, y con la ayuda de un flash de mano, traza el contorno de la selva, obteniendo su huella. A continuación, revela el papel in situ, en medio de la jungla, con agua extraída del río Amazonas.El resultado son piezas monumentales que transmiten el espíritu y la profundidad de la selva, superando el retrato tradicional del paisaje.

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

From the series AMAZOGRAMAS

Year 2014

Photography

Photogram on photosensitive paper

1181.1 × 42.5 in

Unique piece

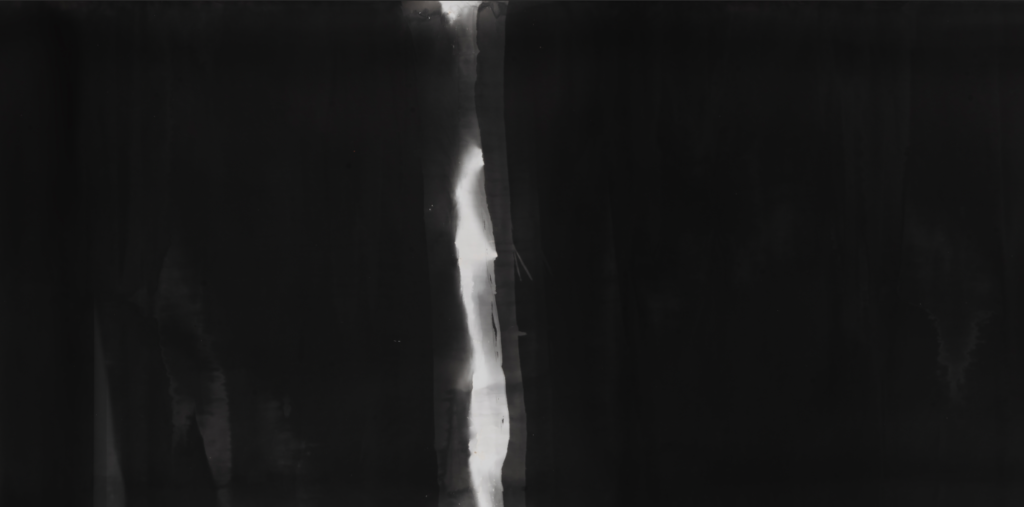

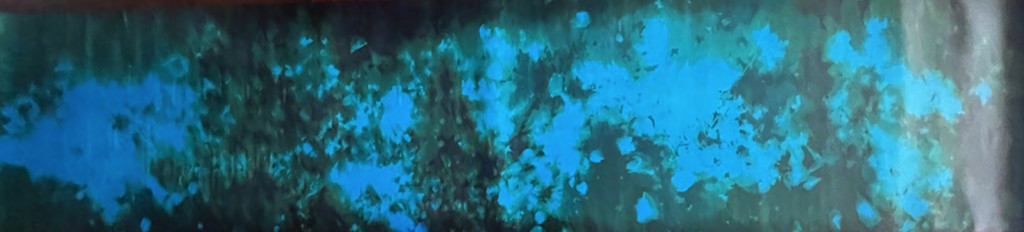

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

From the series AMAZOGRAMAS

Year 2014

Photography

Photogram on photosensitive paper

1181.1 × 42.5 in

Unique piece

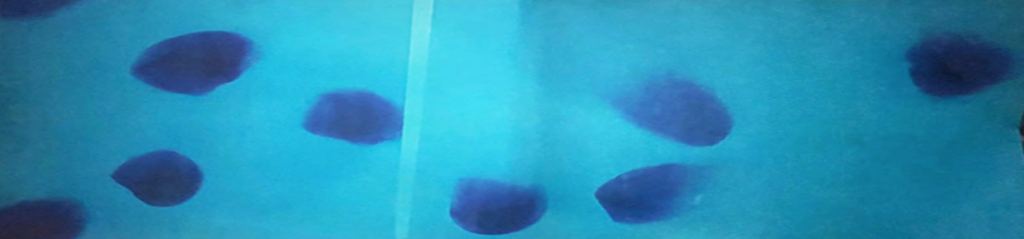

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

From the series AMAZOGRAMAS

Year 2014

Photography

Photogram on photosensitive paper

1181.1 × 42.5 in

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1420 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1420 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1420 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

3000 x 108 cm

Pieza única

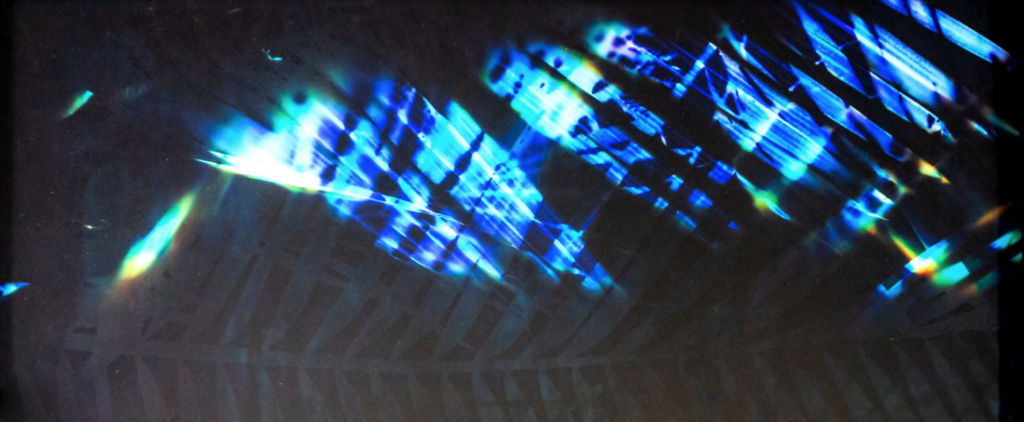

Amazogramas

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

Amazogramas

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

Amazogramas

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1600 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1600 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

1600 x 108 cm

Pieza única

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2014

Caja con 3 fotos enrolladas de 4 m de largo x 15 cmde alto cada una

Impresión inkjet sobre papel de algodón

Texto inglés- españo texto

Edición 100

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

107 x 160 cm

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

400 x 108 cm

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

212 x 108 cm

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

600 x 220 cm

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

107 x 110 cm

De la serie Amazogramas

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

107 x 110 cm

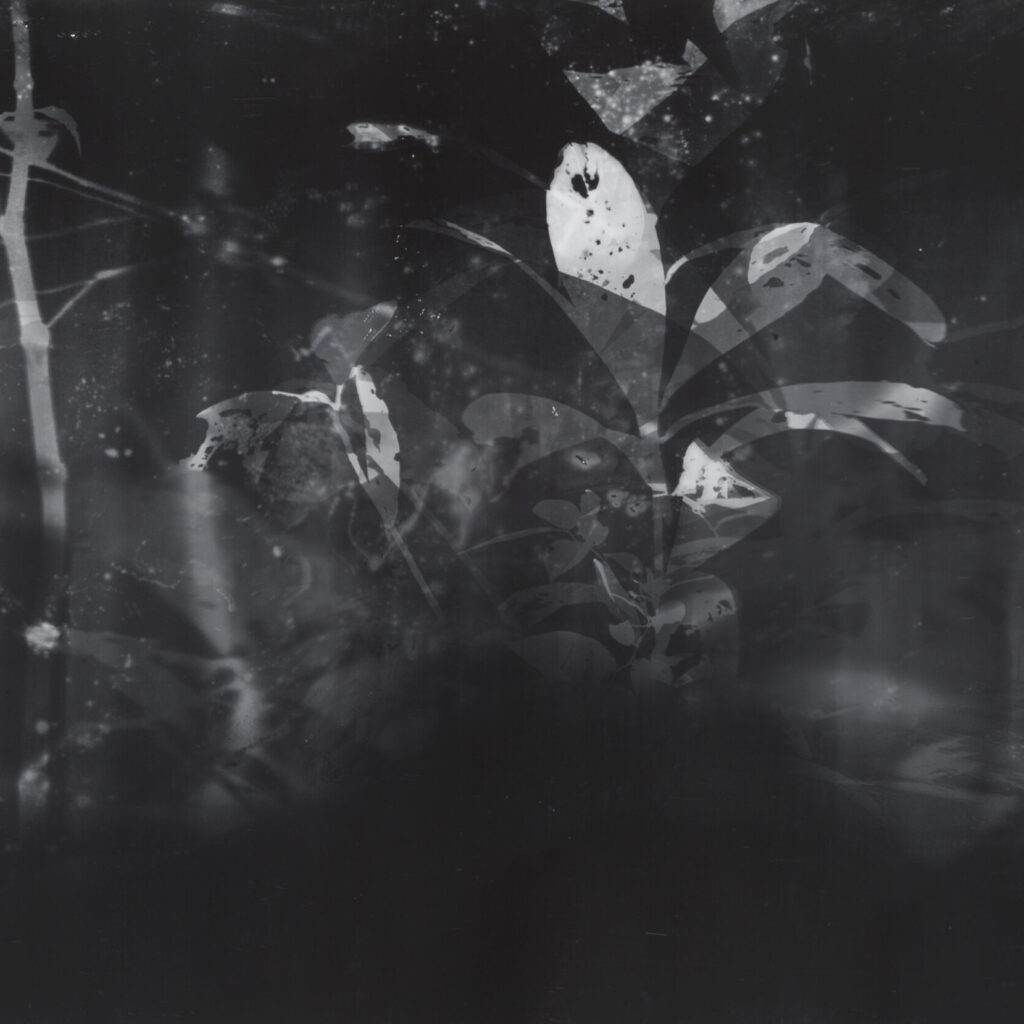

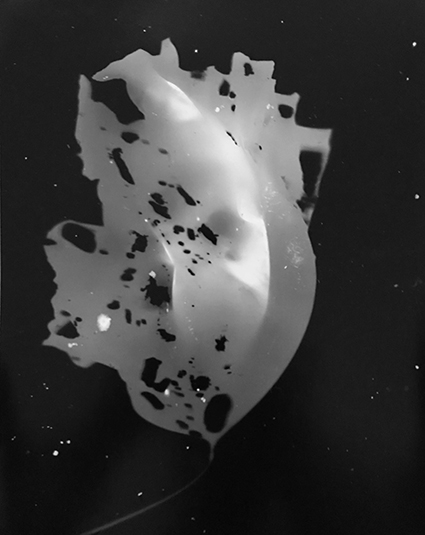

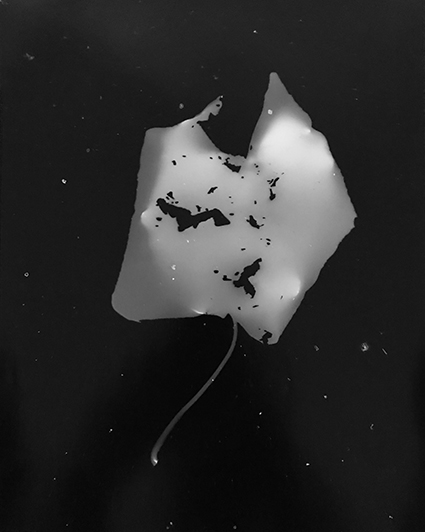

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

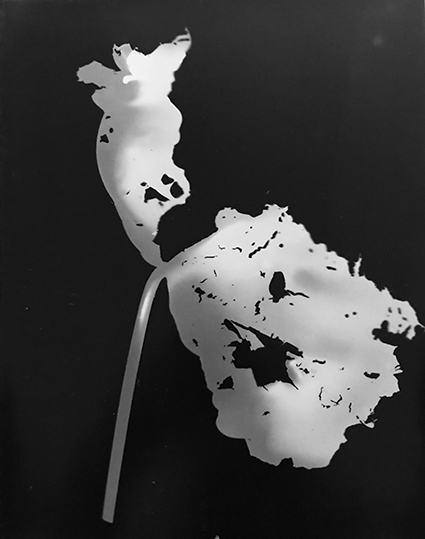

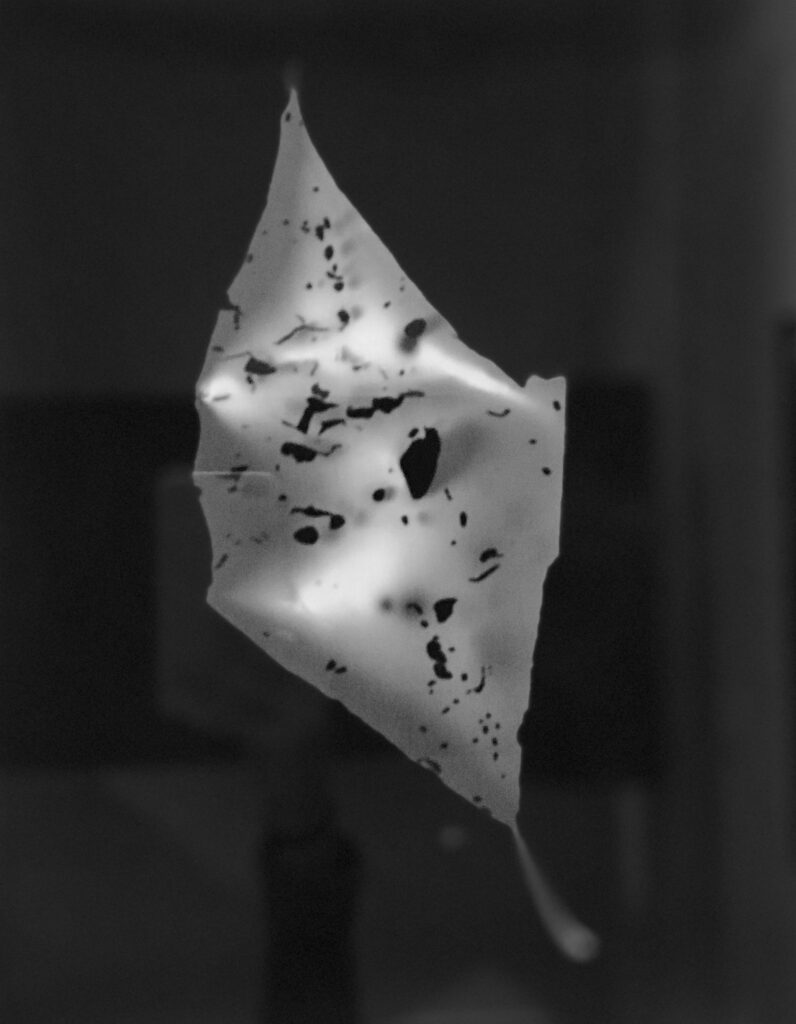

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

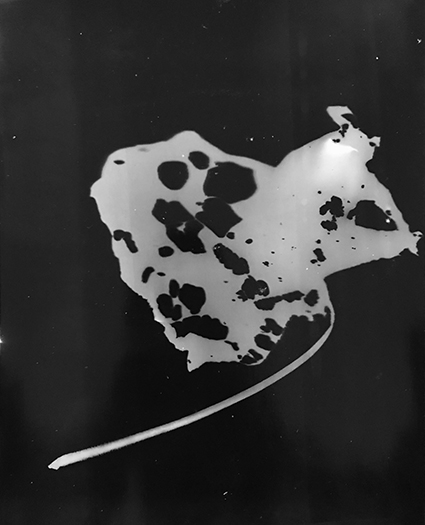

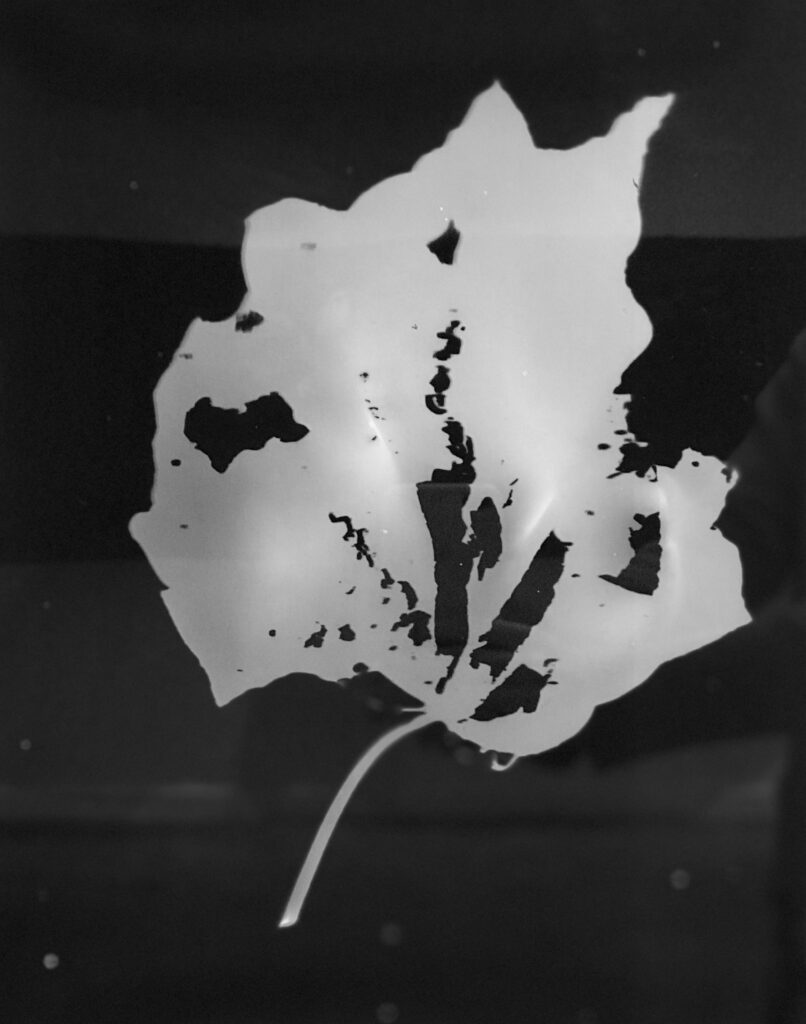

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

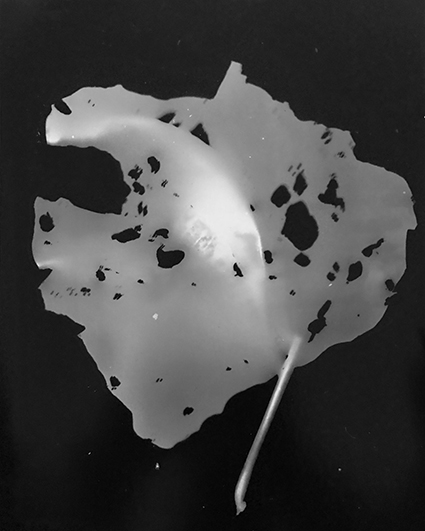

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

De la serie Amazogramas

2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

28 x 36 cm

Pieza única

From the series Amazogramas

Leaves

Year 2018

Photograph

Photogram on photosensitive paper Dimensions 11 x 14.17 in.

Unique piece

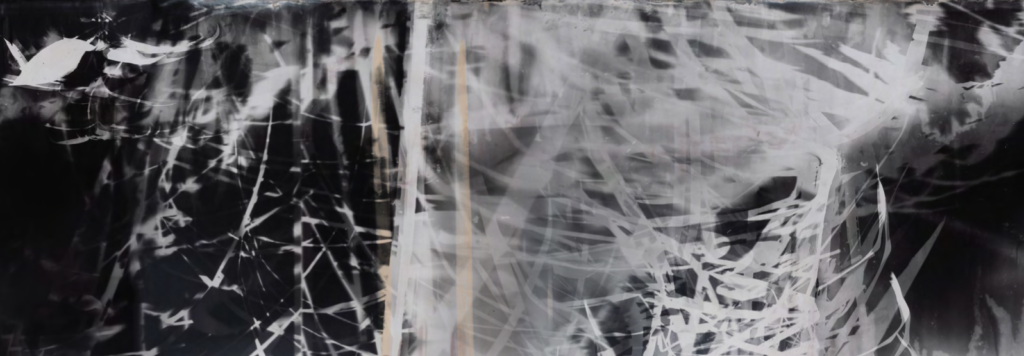

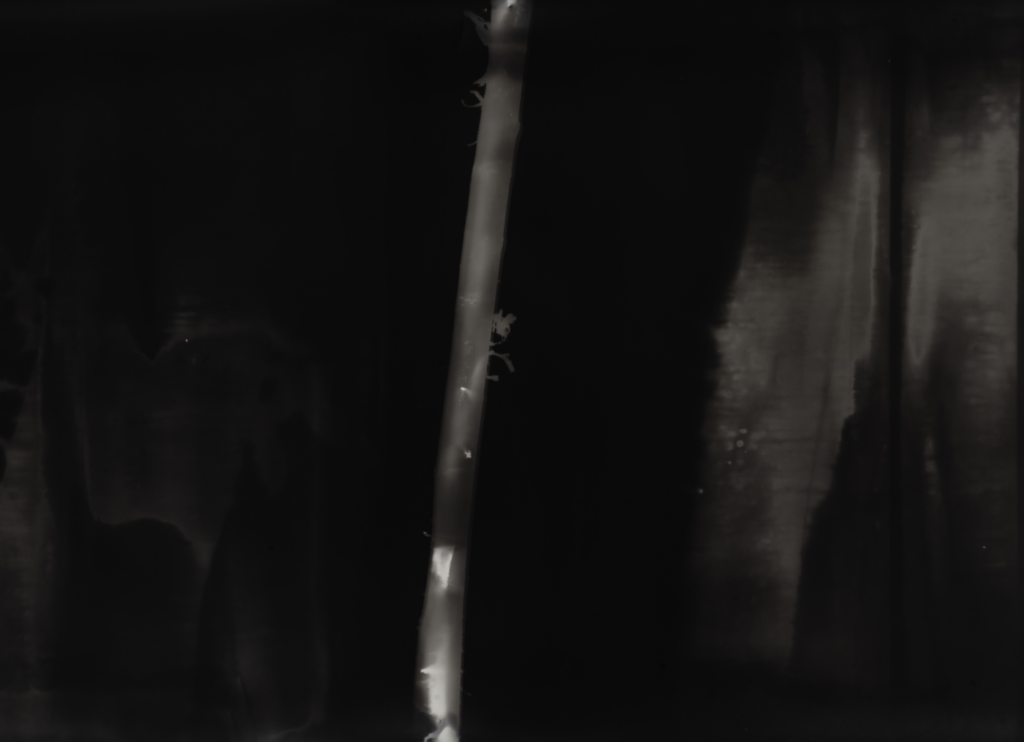

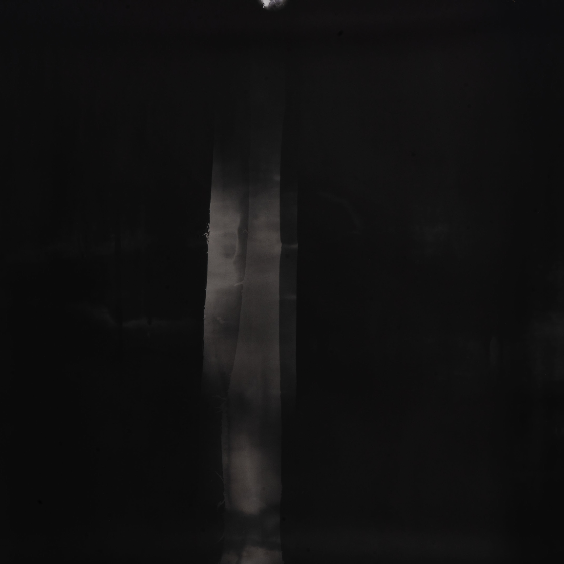

Serie de fotogramas de mediana y gran escala de los bosques de Eucaliptos que se extienden al suroeste de Perú. Desplegando papel fotosensible como una serpiente entre los arboles de Eucaliptus, de noche bajo la luz de la luna llena, y con la ayuda de un flash de mano, obtiene el vasto retrato del arcabuco. A continuación, revela el papel in situ, en medio del monte. El resultado son piezas monumentales que transmiten el espíritu y la espesura de la jungla, superando el retrato tradicional del paisaje.

Series of medium and large-scale frames of the Eucalyptus forests extending southwest of Peru. Unfurling photosensitive paper like a snake among the Eucalyptus trees, at night under the light of the full moon, and with the aid of a handheld flash, capturing the vast portrait of the landscape. Subsequently, developing the paper on-site, amidst the wilderness. The result is monumental pieces that convey the spirit and density of the jungle, surpassing the traditional portrayal of the landscape.

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Sin Titulo I

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

1000 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serieBosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

1000 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

500 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

110 x 160 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

280 x 108 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

113 x 110 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

113 x 110 cm

Pieza Única

De la serie Bosque de Eucaliptos

Año 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible Photogram on photosensitive paper

83 x 110 cm

Pieza Única

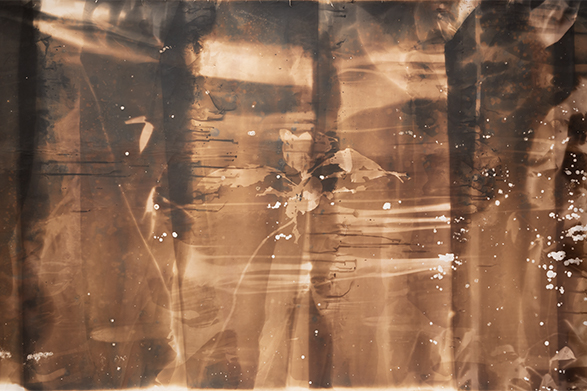

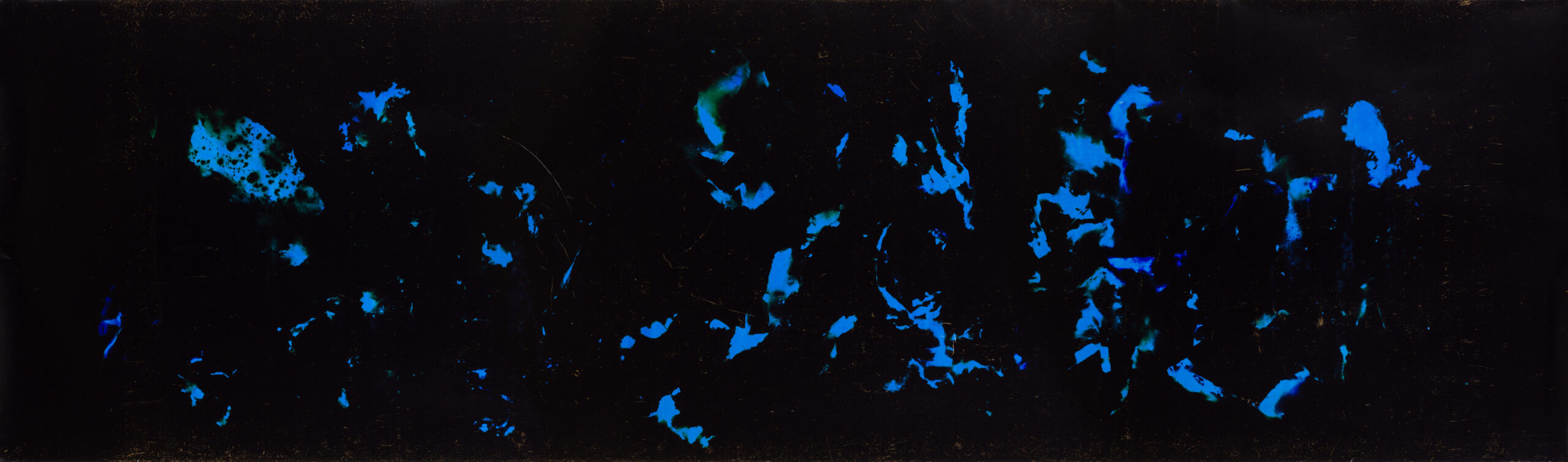

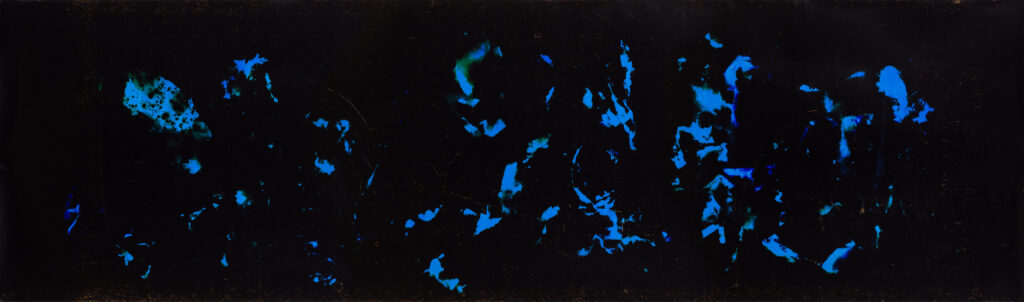

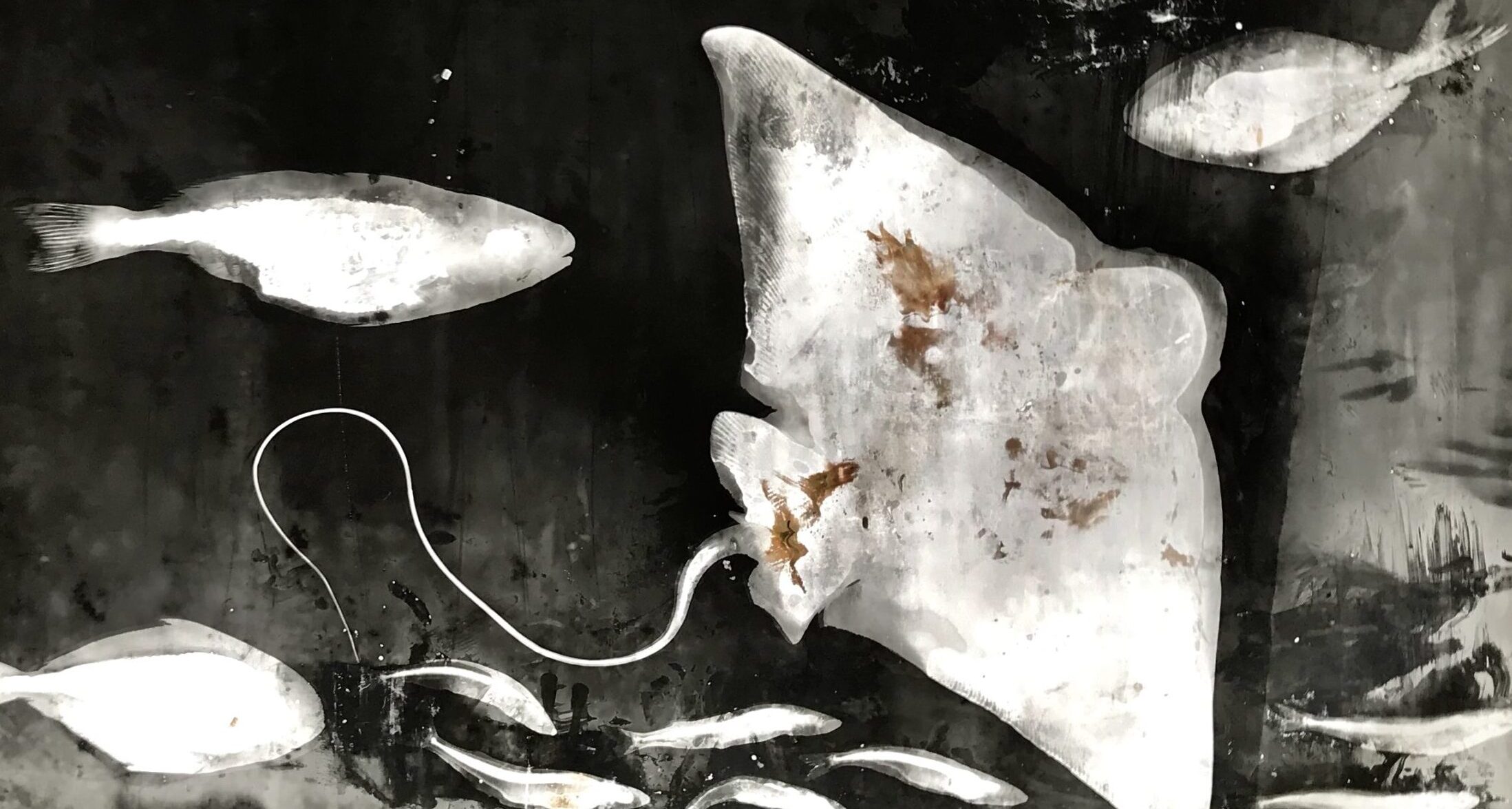

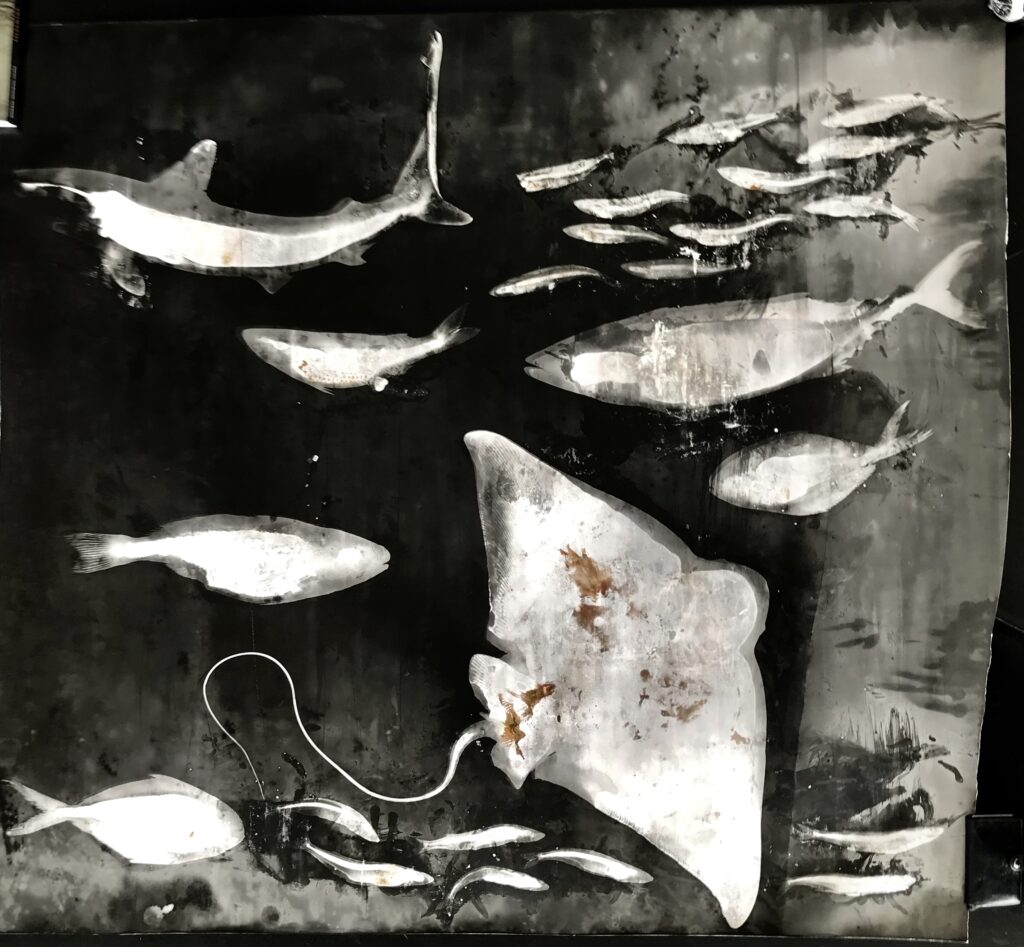

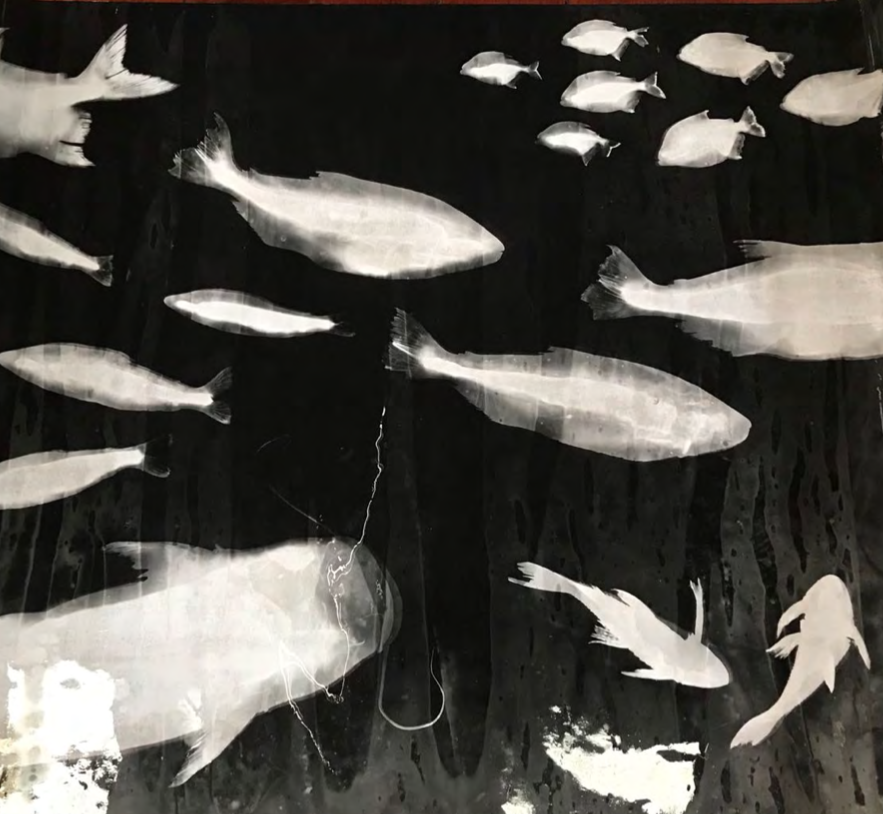

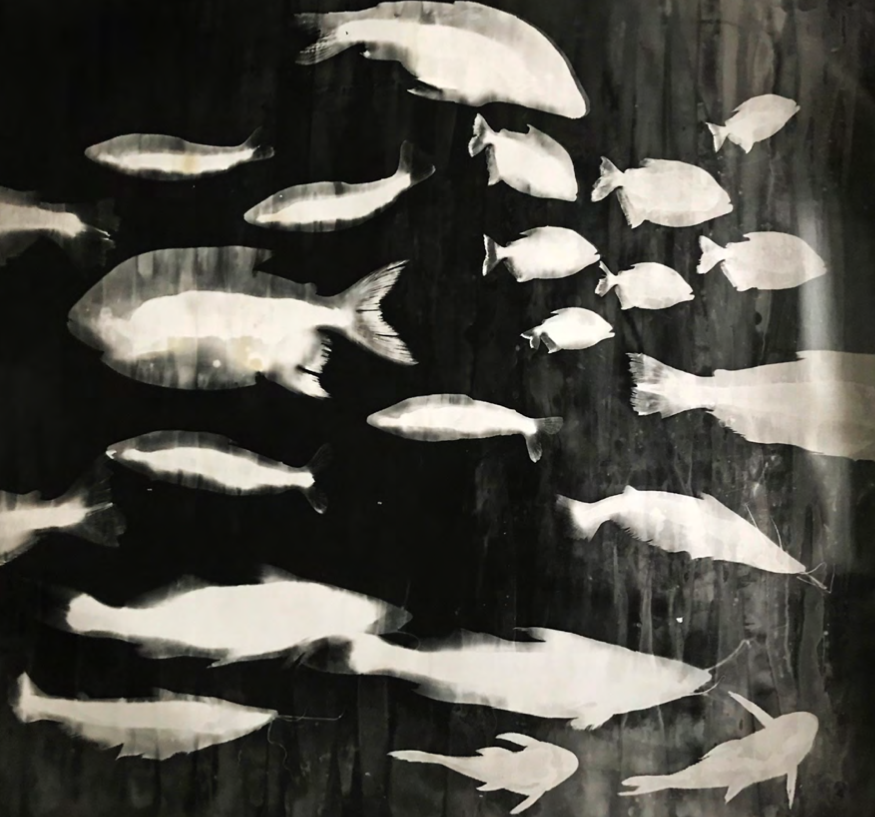

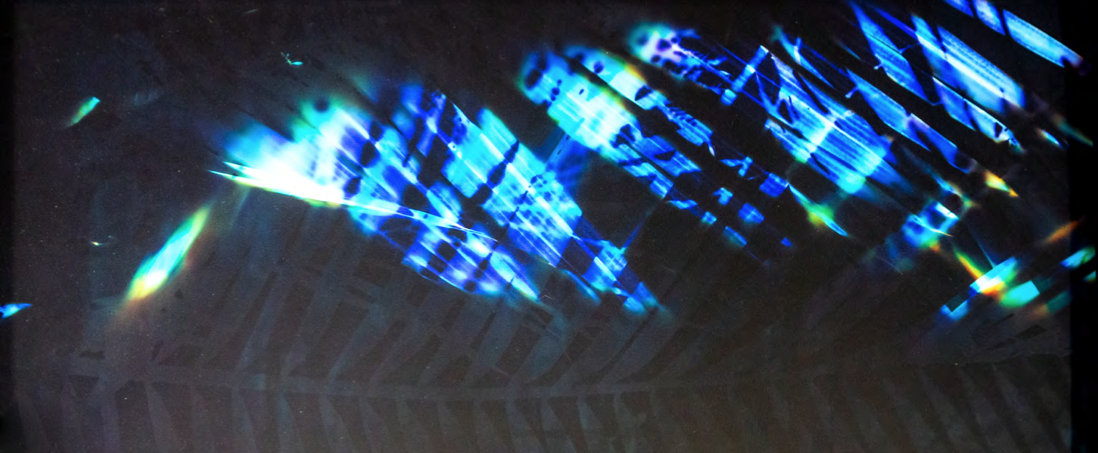

La serie contiene dos partes diferenciadas, la primera presenta los resultados obtenidos, mediante la técnica del fotograma, durante el momento en que el agua del mar llega a la costa e interactúa con el papel fotográfico. Un proceso de generación de imágenes que transciende el control del autor, el cual se convierte en mediador de esa experiencia.

Las huellas que generan el agua y la arena sobre el papel repiten las exploraciones realizadas anteriormente por Roberto Huarcaya en la selva peruana, donde adoptó el rol de los pioneros de la fotografía. Allí recuperó uno de los procedimientos inaugurales de la fotografía: el fotograma. Una técnica que, sin mediar lentes ni cámaras, permitía obtener reproducciones exactas de los objetos. Su inventor, William Henry Fox Talbot, al describir sus primeros experimentos con la técnica del fotograma, escribió con asombro: «La naturaleza se dibuja a sí misma». En Oceanogramas es de nuevo la Naturaleza quién dibuja el relato del encuentro del mar con la costa. Y de nuevo la figura diluida del autor concede al azar un rol protagónico, donde la incertidumbre sobre los resultados forma parte intrínseca del proceso. La posición de Roberto Huarcaya ilustra la necesaria toma de conciencia que debemos de adoptar en nuestra relación con la Naturaleza: el respeto a sus ciclos y a la estructura de sus ecosistemas.

La segunda parte de la serie se centra sobre los vertidos de plásticos al mar, que constituyen uno de los problemas más importantes en la estabilidad del ecosistema marino. Millones de toneladas son arrojadas anualmente al mar, activando un proceso irreversible de contaminación, que afecta a plantas, animales, aves y peces, y que genera una cadena de destrucción que llega también a las personas. Utilizando la técnica del fotograma, esta vez mediante el uso de papel fotográfico de color, Roberto Huarcaya registra la omnipresencia en los entornos oceánicos que ocupan los plásticos en sus diferentes procesos de degradación. Son registros que exhiben con perversa belleza la trágica presencia del plástico en el ecosistema marino: una suerte de flores del mal.

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Basura I

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

400 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Basura II

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

400 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Basura III

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

400 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Basura IV

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

400 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

Océanos

Vista de Instalación

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

Océanos

Vista de Instalación

Traces

ARLES | Les Rencontres de la Photographie

Arles, Francia

2023

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Olas I

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

190 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Océanos

Mar y Olas II

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

390 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | EL PACÍFICO

2018 – 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

76 x 42,5 in

Pieza Única

From the series | EL PACIFICO

2018 – 2019

Photography

Photogram on photosensitive paper

76 x 42,5 in

Unique Piece

De la serie Océanos

Polusión Pacífico I

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

120 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

108 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

116 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

108 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

108 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

108 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

108 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie | OCÉANOS

2018

Fotografía

20 x 25 cm

Tríptico

Fotograma sobre papel fotosensible

Pieza Unica

From the series | OCÉANOS

2018

Photography

7.87 × 9.84 in

Triptych

Photogram on photosensitive paper

Unique piece

Antes de abrazar la fotografía, Huarcaya se formó como psicoterapeuta infantil. Ello quedó expresado en una de sus primeras series, Deseos, temores y divanes (1990), que retrata al terapeuta y al paciente en distintos trances, en varios de los cuales este último aparece como un niño. Poco después, Huarcaya dedicaría una serie al hospital psiquiátrico Víctor Larco Herrea en Lima: La nave del olvido (1994), para la cual pasó tiempo con los pacientes del hospital, enseñándoles cómo funcionaba la cámara fotográfica y animándolos a retratarlo a él. Solo una vez asegurada una relación empática, les proponía retratarlos. Desde entonces, Huarcaya ha aplicado una metodología similar en múltiples proyectos en que usa la fotografía para fortalecer la identidad y despertar la creatividad en niños en condiciones de vulnerabilidad.

En su serie Campos de batalla (2010-2011), Huarcaya recurrió a la fotografía panorámica de paisajes para ir construyendo una visión del Perú a partir de los escenarios de batallas decisivas para la historia del país: desde tiempos prehispánicos, pasando por conquista española y la Independencia hasta conflictos más recientes como el asesinato de periodistas en el poblado de Uchuraccay (1983) y el atentado con coche bomba en la calle Tarata en Lima (1992), durante los años de la violencia desatada por Sendero Luminoso.

Ambas líneas de trabajo se relacionan con los dos cuerpos más importantes de fotografías del mundo andino peruano realizadas en los años ochenta y noventa del siglo pasado: las del proyecto TAFOS y las recogidas en la muestra Yuyanapaq. Para recordar que acompañó el informe final de la Comisión de la Verdad sobre el conflicto armado desatado por Sendero Luminoso. TAFOS (Talleres de Fotografía Social) dotó de cámaras y de capacitación en su uso a pobladores de barriadas de Lima y poblados andinos para generar un registro fotográfico de la vida de comunidades socioeconómica y culturalmente marginadas que respondiera a la visión de sus propios miembros y evitara ‘la mirada del otro’ en el registro. Yuyanapaq recogió imágenes de archivos fotográficos que documentan los años de la violencia (1980-2000) y que ponen de relieve no solo las atrocidades de la guerra, sino la identidad andina y campesina de la mayoría de las víctimas.

En este contexto se comprende por qué uno de los Andegramas (Patacancha) no es un fotograma del paisaje andino sino un retrato de 36 niños de la comunidad de Patacancha ataviados con sus vestimentas tradicionales, realizado en el marco de un taller de fotografía ofrecido por Huarcaya y Pablo Ortiz Monasterio en dicha comunidad, reconocida por mantener su ancestral tradición de confecciones textiles: fueron los propios niños los que imprimieron su imagen, echándose sobre un rollo de 18 metros de largo de papel fotográfico. En la pieza resuenan, entonces, la intención de dotar de voz propia a los pobladores andinos, como en TAFOS, y la superación de la etapa de la violencia recogida en Yuyanapaq, así como el acercamiento pedagógico a la fotografía, el retrato y la búsqueda de identidad –arraigada en la historia colectiva y en la niñez– como en los trabajos de Huarcaya anteriormente citados. Frente a la selva bella, ominosa y sin tiempo de los Amazogramas, los Andegramas incorporan la historia humana y la realzan con el orgullo por la propia cultura y la risa y el juego de los niños en señal de esperanza.

De la serie Andegramas

Patacancha (detalle)

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1800 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Patacancha

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1800 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Patacancha (detalle)

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1800 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Q’eros I (detalle)

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Q’eros I

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Q’eros I (detalle)

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Andegramas

Q’eros II (detalle)

Año 2017

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 108 cm

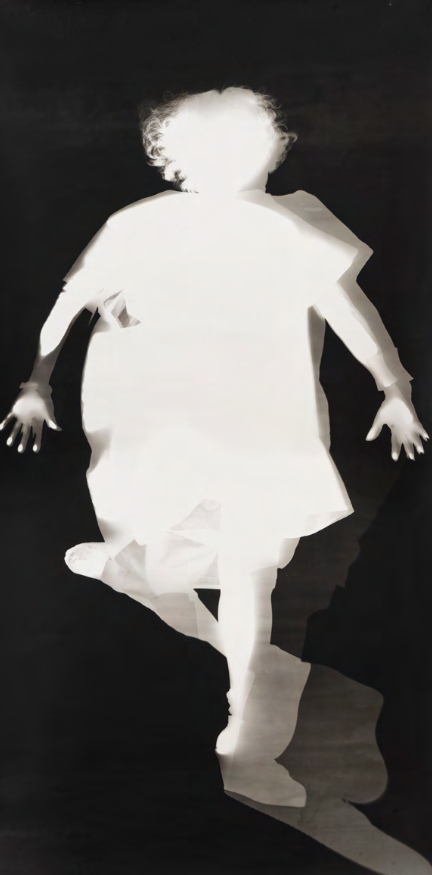

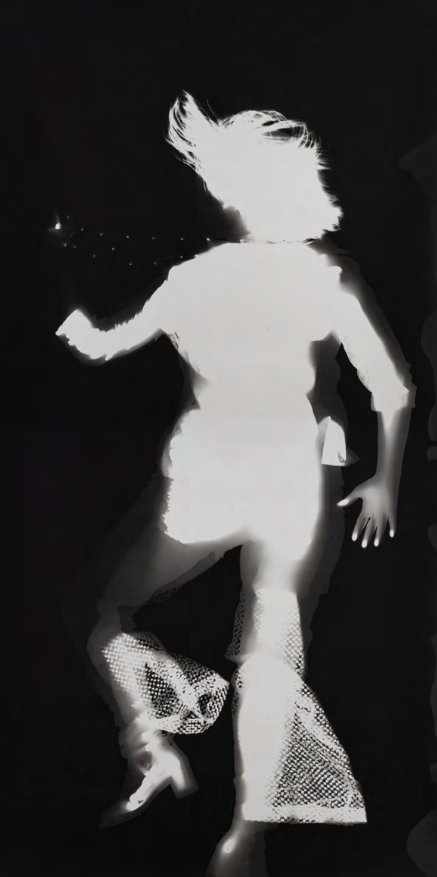

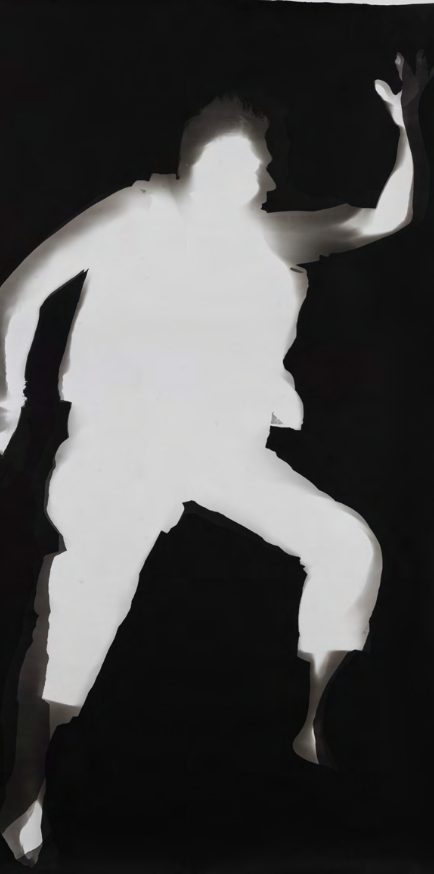

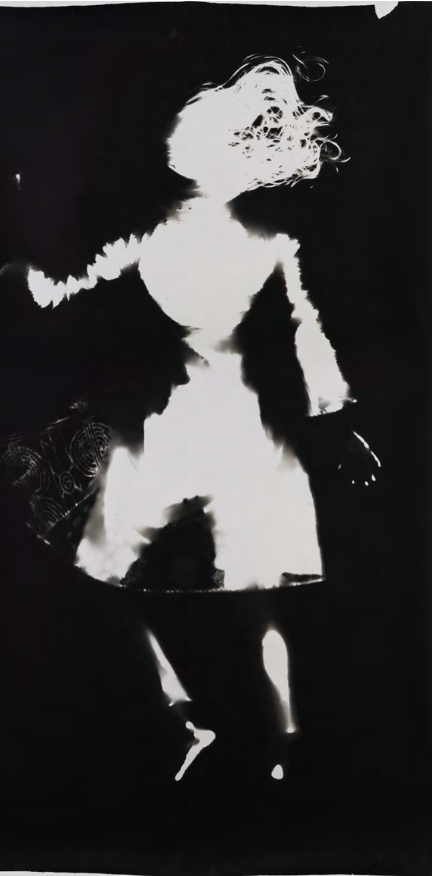

Pieza Unica

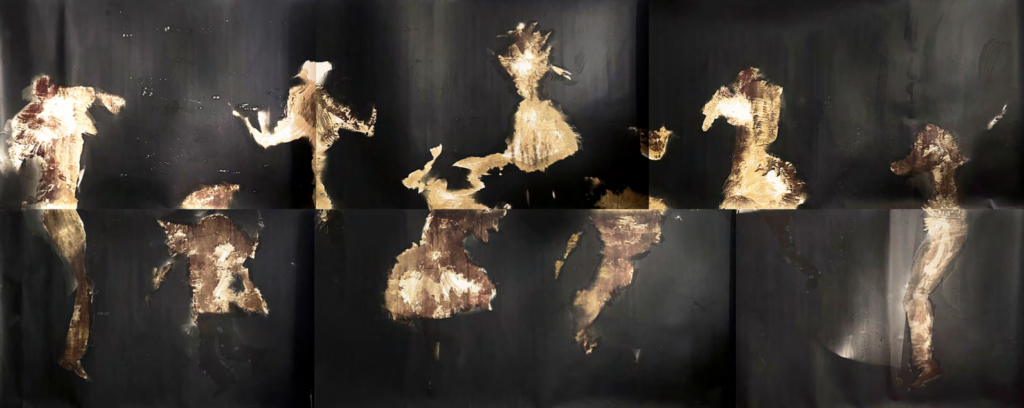

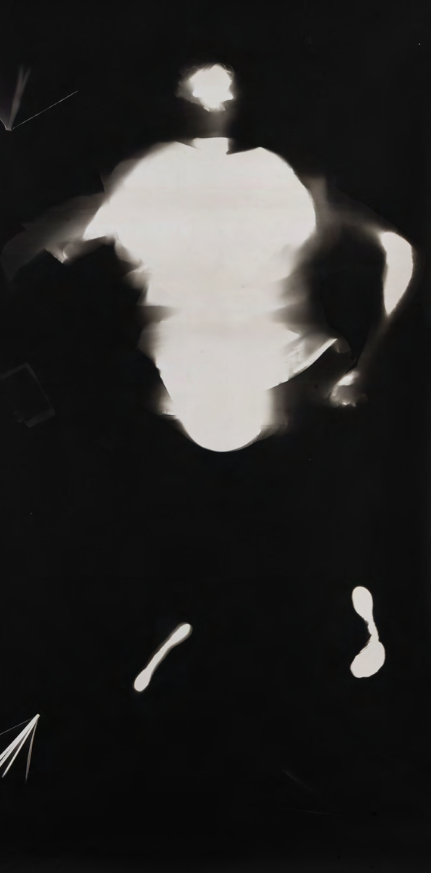

Danzas Andinas es una de las series pertenecientes al ambicioso proyecto de fotogramas de Roberto Huarcaya, a través del cual representa las grandes regiones geográficas del Perú. Está compuesto por dibujos fotogénicos: “Niños Danzantes de Tijeras”, “Padres Danzantes de Tijeras” y “Músicos Andinos Koyurqui”, que introducen al proyecto de Huarcaya (que ya involucra la naturaleza y el territorio geográfico), la presencia humana, la historia y la cultura, al mismo tiempo que aborda problemáticas geopolíticas vinculadas al territorio del Perú.

La danza de tijeras fue reconocida por Unesco en 2010 como Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial de la Humanidad. La danza deriva su nombre de las dos hojas de metal pulido, parecidas a las de un par de tijeras, que los danzantes entrechocan, para hacer un ruido como de campanas, mientras bailan. El baile generalmente toma la forma de un desafío entre los bailarines, que puede durar varias horas, en el que, a su vez, cada uno intenta copiar los pasos del otro, convirtiéndose en demostraciones acrobáticas más complejas, resistencia e incluso auto-laceración.

Sus orígenes se vinculan con el taki onqoy (“enfermedad del baile”), movimiento mesiánico surgido en los Andes del sur del Perú hacia 1560, que nació de la conversión de un ritual de sanación, mediante el trance y el baile, en un movimiento de resistencia contra la dominación española. Con el tiempo, el taki onqoy se ejercería no sólo contra las enfermedades, sino también contra lo que se consideraba su fuente: el abandono del culto de los Huacas o las deidades andinas debido a la extirpación de las idolatrías y la evangelización impuesta por la Iglesia Católica. Los profetas del movimiento instaron a los colonos andinos a revivir la adoración a los Huacas, permitiéndose ser poseídos por ellos a través de la danza. Gracias a esto, los huacas se levantarían en armas contra el dios cristiano que los había derrotado en el momento de la conquista, para desterrarlo del mundo andino y establecer una nueva era de orden y prosperidad. Como movimiento, el taki onqoy fue reprimido y desarticulado en 1572, pero los expertos coinciden en que su visión mesiánica subsistió y constituyó parte de las rebeliones indígenas posteriores contra el dominio español. Ya en el siglo XX, la danza de las tijeras se ve asociada tanto con las fiestas patronales de raigambre católica como con

as celebraciones del calendario agrario andino. El masivo proceso migratorio de los Andes a las ciudades de la costa peruana, acaecido desde mediados del siglo pasado, ha llevado esta danza al contexto urbano, en donde se ha convertido en una manifestación de carácter folclórico, aunque mantiene aún aspectos rituales, pues se sigue creyendo que cada danzante deriva su destreza de un huamani o deidad y la danza se transmite de maestro a discípulo e implica ritos de iniciación; por tanto, sigue siendo una práctica fuertemente identitaria en términos culturales.

Para lograr la pieza de los Niños Danzantes de Tijeras, Huarcaya recurrió a un complejo proceso de varios registros. En primer lugar, los niños danzantes de tijeras se acostaron sobre el papel fotográfico para generar un fotograma de sí mismos. Huarcaya luego digitalizó fragmentos del Andegrama de Patacancha (de la serie Andegramas, realizada a 5000 metros en comunidades impenetrables del Perú) y los imprimió por impresión de tinta sobre un papel traslúcido. Esto fue utilizado como negativo para volver a exponer el fotograma, esta vez mediante la técnica del marrón Van Dyke (emulsión de citrato férrico y nitrato de plata) y para revelar una vez más. Así, las imágenes de los niños danzantes de tijeras de Lima y de los niños de Patacancha, son combinadas.

Los Padres Danzantes, que preceden a Los Niños Danzantes, fueron tratados mediante un proceso similar de fotogramas emulsionados con el pigmento marrón Van Dyke, pero en lugar de volver a exponerlos con el fragmento Patacancha, el artista utilizó telas precolombinas de más de mil años, que permitía incorporar la textura y la forma de estos textiles a los cuerpos de los bailarines. Ambas obras están acompañadas de una pista de audio de la música folklórica.

Estamos, pues, ante una pieza monumental, no solo por sus dimensiones, sino por el modo en que amalgama diferentes significados de singular trascendencia.

Junto a estas obras, los “Músicos Andinos de Koyurqui” y la serie Andegramas incorporanalproyectodeHuarcaya,lahistoriahumanayelorgullodelapropiacultura.

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras (detalle)

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

440 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras (detalle)

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

440 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras (detalle)

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

440 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras II (detalle)

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

360 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras II

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

360 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Niños danzantes de tijeras II (detalle)

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

360 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Padres danzantes de tijeras (detalle)

Año 2018 – 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 216 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Padres danzantes de tijeras

Año 2018 – 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 216 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Padres danzantes de tijeras (detalle)

Año 2018 – 2019

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

1000 x 216 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Danzantes voladores

Año 2018

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

650 x 220cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Danzantes andinos I

Año 2020

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

290 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Danzantes andinos II

Año 2020

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

320 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Danzas Andinas

Danzantes andinos III

Año 2020

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

300 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

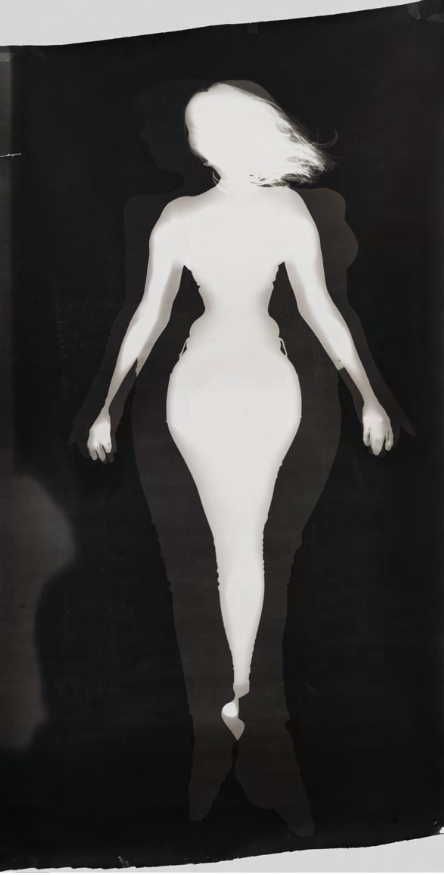

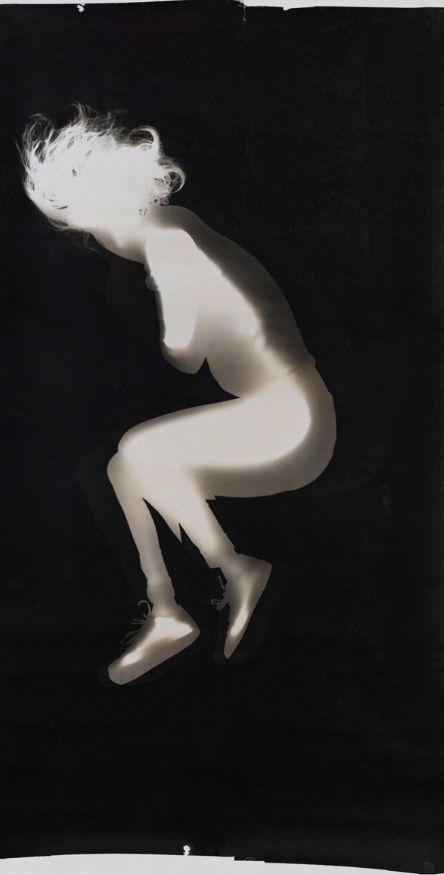

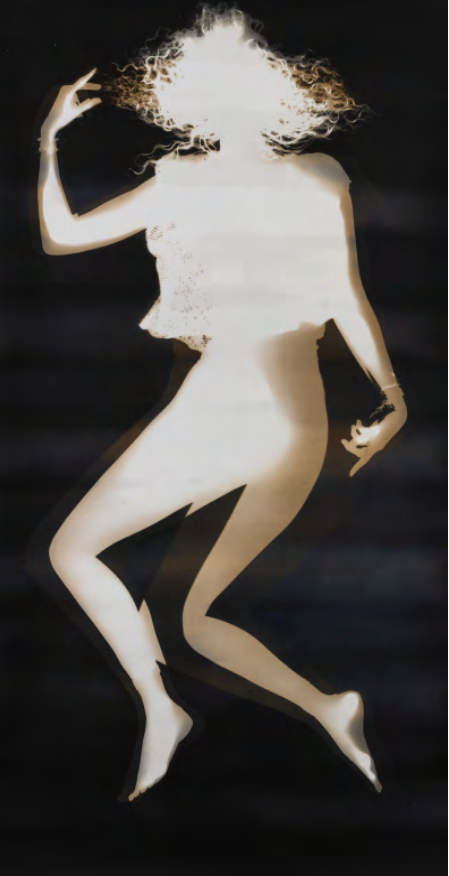

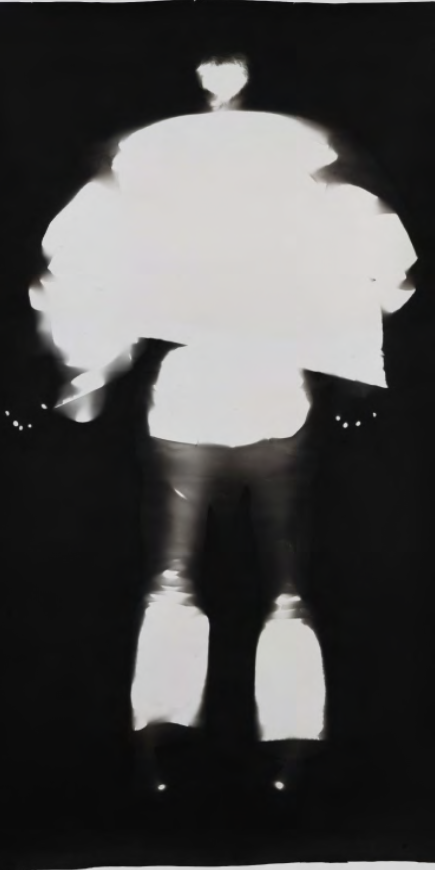

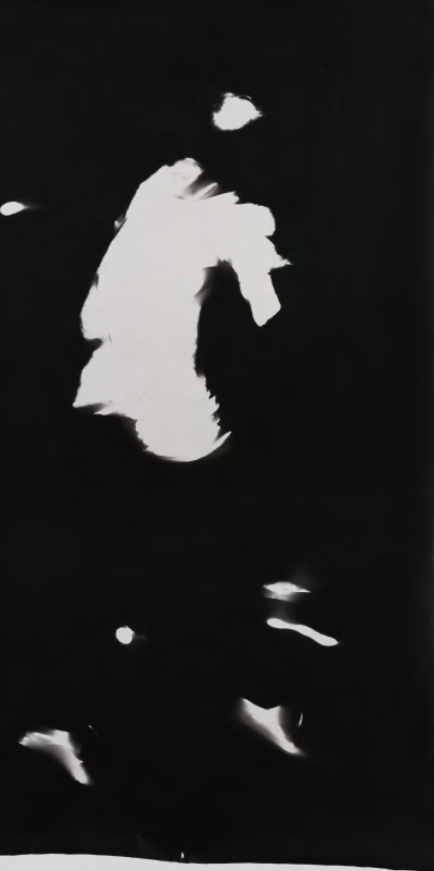

Cuerpos develados de Roberto Huarcaya es una serie de retratos realizados con la técnica del fotograma. Los retratados son personajes vinculados a la fotografía latinoamericana: fotógrafos, críticos, galeristas, coleccionistas, de muchos países que dejan su sombra, su huella directamente sobre el papel fotosensible.

Cada retrato está hecho directamente en papel fotosensible de 2.20 m x 1.10 m. En un espacio totalmente oscurecido, le pido a cada participante que se recueste directamente sobre el trozo de papel y que se ponga cómodo, que haga suyo ese pequeño territorio. Cuando me comunica que está cómodo sobre el papel, realizo dos o tres disparos con un flash desde posiciones distintas tratando de generar, con la suma de las sombras, una imagen con más información y más volumen. Son piezas a escala de 1 a 1 con los representados, siendo además cada una de ellas piezas únicas.

Roberto Huarcaya

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Anamaria McCarthy

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Camila Rodrigo

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Gihan Tubbeh

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Graciela Iturbide

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Guadalupe Miles

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Julieta Escardó

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Maya Goded

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Paz Errázuriz

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Rosângela Rennó

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Tatiana Parcero

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Antoine D’Agata

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Luis Gonzalez Palma

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Joan Fontcuberta

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Juan Travnik

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Luis Camnitzer

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Luis Weinstein

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Cuerpos develados

Marcos López

Año 2017 – 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 108 cm

Pieza Unica

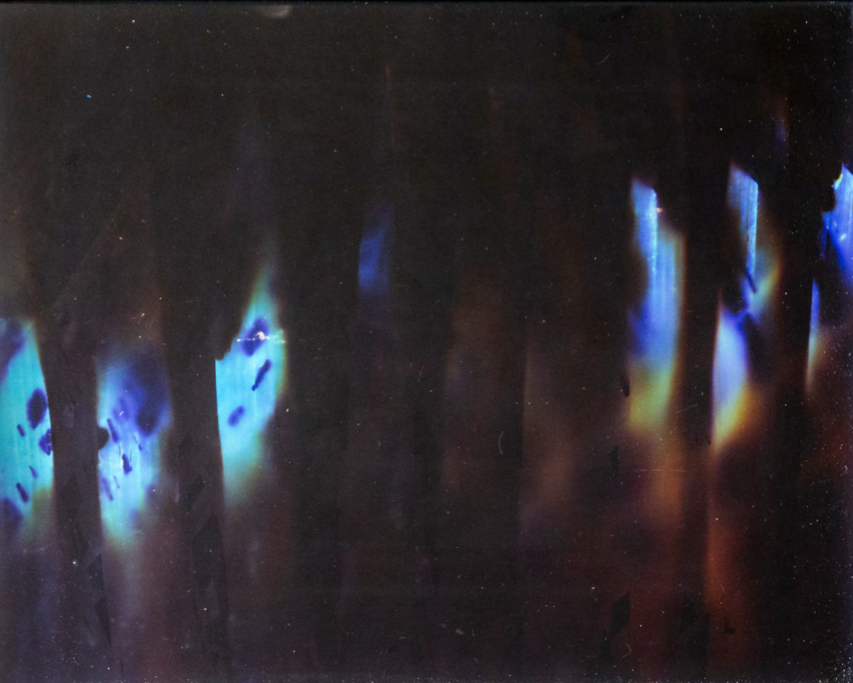

Esta imagen es parte del nuevo proceso de investigación visual del trabajo en la Amazonía. Al cambiar el soporte del papel fotosensible blanco y negro por el papel fotosensible a color he experimentado las grandes diferencias visuales que se dan entre ambos procesos.

Roberto Huarcaya

De la serie Amazonía a color

Amazonia Azul II

Año 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

166 x 126 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Amazonia Azul III

Año 2024

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

300 x 60cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Energia IV

Año 2024

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

143 x 63 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Oscuro Azul III

Año 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

63 x 94 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Palmera Amazonia Azul

Año 2024

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

220 x 220 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Oscuro Azul I

Año 2024

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

44 x 54 cm

Pieza Unica

De la serie Amazonía a color

Oscuro Azul II

Año 2023

Fotografía

Fotograma sobre papel color fotosensible

44 x 54 cm

Pieza Unica

Desde hace más de una década, el artista visual Roberto Huarcaya recorre el territorio peruano (desde los bosques de la Amazonía hasta las costas del Pacífico pasando por las montañas de los Andes) realizando fotogramas “monumentales” que pueden llegar a alcanzar hasta 30 metros de longitud. A medio camino entre la fotografía, la instalación y el land art, los fotogramas de Huarcaya, realiza- dos de manera experimental y recurriendo a técnicas como la cianotipia o el Marrón de Van Dyke, adquieren formas orgánicas —espirales, laberintos, zigzags, cascadas, ondas— que, adaptándose a las condiciones expositivas, ofrecen una experiencia inmersiva que no solo solicita la vista de los visitantes, sino que con- voca la totalidad de sus cuerpos, desafiando así sus hábitos atencionales.

Huarcaya congrega elementos heterogéneos —tierra, agua, plantas, insectos, animales— en superficies fotosensibles de gran formato para que, en simbiosis con los fotones (energía lu- mínica) procedentes de fuentes como el sol, la luna, los rayos o el flash, provoquen el adveni- miento de imágenes. Las relaciones de fuerza entre los distintos agentes —los materiales, las circunstancias, el artista y sus colaboradores— involucrados en el proceso de formación de dichas imágenes-trazas son orgánicas, dinámi- cas, abiertas y horizontales. “Rizomáticas” diría el filósofo Gilles Deleuze1. Huarcaya renun- cia entonces al deseo de controlar las distintas etapas del proceso creativo (por ello él prefiere calificarlo como un “anti-proceso”), así como la forma final de sus resultados, reivindicando con ello un trabajo artesanal experimental que reconoce la relatividad del tiempo y del espa- cio, que admite la idiosincrasia de la materia y que acoge la irreductibilidad de la experiencia. Por tanto, en el proceso de generación de los fotogramas, Huarcaya opera simplemente como un médium que, guiado por su intuición y su experiencia, acepta, en palabras Hartmut Rosa, la “indisponibilidad del mundo”, el ca- rácter imprevisible de lo viviente.

Las huellas cósmicas suscitadas/incitadas por Huarcaya son imágenes de la naturaleza en los dos sentidos implicados en el genitivo “de”. Por un lado, son imágenes de la naturaleza porque representan, a medio camino entre la abstracción y la figuración, fragmentos de la realidad (genitivo objetivo). De esta manera, en los términos semiológicos inaugurados por Charles Sanders Peirce, las imágenes-trazas son signos que significan y refieren a entida- des del mundo. Por otro lado, son imágenes de la naturaleza porque han sido, como sostiene André Bazin, ontológicamente generadas por entidades del mundo4 (genitivo subjeti- vo). En tal sentido, dialogando con la tradición inaugurada por William Henry Fox-Talbot en The Pencil of Nature (1844-1846), las imágenes- trazas (de)muestran la capacidad de la natu- raleza para expresarse a través de su propia autorrepresentación. Por ello, los fotogramas nos invitan a cuestionar la posición de poder que el hombre moderno se ha arrogado en/ sobre el mundo, devolviéndole al cosmos de manera simbólica la “agencia”5 que la cultura occidental, fundada en una ontología “natura- lista” y promotora de una política “reificante”, le ha negado.

Al recurrir a una técnica de producción de imá- genes que prescinde del aparato fotográfico, Huarcaya no expresa una relación nostálgica ni fetichista con el periodo analógico de la Historia de la fotografía, sino la elección cons- ciente y meditada de un medio de expresión y de comunicación, y de un método de creación y de investigación, que operan, como lo exigía Vilém Flusser, contra las reglas del aparato fotográfico, es decir, libremente. Por ello, su práctica artística se ubica a contraco- rriente de las tendencias tecnófilas actuales que promueve el uso de tecnologías “de punta” —cámaras digitales, imágenes de síntesis, inteligencia artificial, imágenes operatorias— que están al servicio de procesos programa- dos de producción de visualidad automatizada para satisfacer las demandas del capitalismo financiero. De tal forma, adoptando una postura crítica y reflexiva ante las demandas de su propia contemporaneidad, Huarcaya se aleja del programa de la cámara fotográfica realizando así un doble movimiento deconstructivo de la Representación del Mundo enarbolada por el Espíritu moderno: por un lado, cues- tiona al oculocentrismo (término que designa la organización de la realidad constituida en/ por el campo de representación emergido del privilegio otorgado a la visión por sobre otras formas de percepción); por el otro, cuestiona el logocentrismo (término que designa la organización de la realidad constituida en/por el campo de representación emergido del privilegio otorgado al pensamiento racionalista por sobre otras formas de cognición).

Los fotogramas rompen con el oculocentrismo pues no son expresión de un ver óptico sino de un ver háptico, es decir, no constituyen un medio de representación que transcribe a distancia y por similitud la apariencia del mundo (iconos), sino un medio de representación que inscribe en proximidad y por contacto la mate- rialidad del mundo (índices). Debido a ello, los fotogramas se alejan de la forma de representación que, imitando la supuesta percepción natural (“naturalista”) a partir del dominio tecnocientífico de la perspectiva, ha sido he- gemónica durante la modernidad occidental. Al abandonar esta codificación óptica de la realidad, los fotogramas de Huarcaya también rompen con el logocentrismo pues dejan de ser imágenes útiles para la alianza ideológica establecida entre el positivismo científico, el colonialismo geopolítico y el capitalismo eco- nómico, quienes se han servido de la represen- tación naturalista con la finalidad de conocer, controlar, dominar y consumir al mundo9. Así, al cuestionar los fundamentos perceptivos (oculocentrismo) y cognitivos (logocentrismo) de esta forma de representación, la obra de Huarcaya escapa a la representación exotizante con la que la estética moderna ha dibujado el imaginario de los territorios del Sur global y a la representación objetivante con la que la ciencia moderna ha configurado nuestro en- tendimiento de dichos territorios. Por ello, su obra propone una crítica icono-ideológica de la posición que el fotógrafo y la fotografía han jugado en el sistema-mundo configurado por la sociedad capitalista durante los últimos 200 años.

Huellas cósmicas es un proyecto expositivo colaborativo concebido por Roberto Huarcaya para el Pabellón peruano en la Bienal de Venecia 2024. La propuesta está conformada por una pieza del propio Huarcaya y por las obras de dos artistas invitados: Antonio Pareja y Ma- riano Zuzunaga. La obra de Huarcaya consiste en un fotograma de una palmera realizado en la amazonía peruana que, gracias a su insta- lación en forma de cascada, nos sugiere la existencia de una conexión entre el mundo de arriba y el mundo de abajo. Por su parte, el escultor peruano de origen ayacuchano Antonio Pareja colabora con una escultura en madera de una canoa que contiene figuras animales que se funden, y confunden, con la materia de la embarcación. Animales que devienen canoa y, al devenir canoa, devienen madera. Finalmente, el fotógrafo y músico peruano residen- te desde hace 40 años en Barcelona (España), Mariano Zuzunaga, participa componiendo y ejecutando una pieza para piano inspirada en el sonido cósmico. De tal manera, esculpiendo el tiempo, esculpiendo la materia y esculpien- do la luz, la circulación significante entre las tres obras, y entre el espacio que se crea entre ellas y los cuerpos de los visitantes, propone un viaje sideral fuera de nuestro tiempo histórico. Huellas cósmicas no es, por lo antes señalado, una propuesta artística representacional: la instalación, entendida como el agenciamiento de las tres piezas mencionadas, y de los elementos materiales e inmateriales que com- ponen el pabellón, no habla sobre tal o cual tema. Huellas cósmicas es, por el contrario, una propuesta artística presencial: es inmersiva, pues implica/involucra a los visitantes con- virtiéndolos en parte integrante y activa de la instalación; es performativa, pues su carácter inmersivo no demanda de los visitantes (con- vertidos ahora en inter-actuantes) un ejercicio hermenéutico interpretativo, sino una actitud fenomenológica experiencial (lo importante no es qué significa sino cómo los afecta); es transitiva, pues a través de la inmersión y de la performatividad, pretende transferirle a los interactuantes la indeterminación epistémica vivida por Huarcaya y sus invitados durante sus propios procesos creativos. Así, gracias al manejo de la iluminación (natural y artificial), del sonido ambiental, del espacio y del tiempo, de los volúmenes que los ocupan, de la circulación de los cuerpos que los habitan, de las sombras que se generan y de los tres elemen- tos nucleares de la instalación (el fotograma, la escultura y la composición), Huellas cósmicas genera un espacio-tiempo de experiencia no ordinaria que produce un “encuentro”11 que apunta a cuestionar nuestros códigos per- ceptivos, afectivos y cognitivos normalmente modelados para adaptarse a las expectativas funcionales del sistema-mundo capitalista, invitándonos así a redefinir nuestra forma de sentir, de pensar y de ser en el mundo (y de hacer mundo, por tanto).

La pieza seleccionada para el proyecto de instalación en la Bienal de Venecia es un fotograma muy especial por diversos motivos. Es el primer fotograma monumental que realicé bajo circunstancias muy particulares y que me sirvió, en tanto experiencia, para replantear mi vínculo con la naturaleza y con esto mis metodologías y estrategias de trabajo.

Luego de dos años de múltiples viajes y experiencias, llegué a la conclusión que las cámaras fotográficas solo eran capa- ces de registrar lo que se podría llamar la “epidermis de la selva”. La dictadura de la cámara fotográfica imponía su tradición y la Amazonía se resistía a ser retratada bajo esos parámetros.

El fotograma —técnica primaria que pres- cinde de la cámara fotográfica y que necesita estar en contacto directo con la realidad para producir una imagen— era quizás la técnica capaz de resolver el impasse en el que me encontraba.

Gracias al formato monumental del papel fotosensible de 30 metros este podía ex- tenderse en la Amazonía como si fuese el cauce de un río o una serpiente.

Para realizar un fotograma, necesitamos, por un lado, el papel fotosensible y, por el otro, una fuente de luz. Un pequeño flash de mano servía para exponer la naturaleza, y su sombra, proyectada sobre el papel, dejaría su huella en negativo, para luego pasar a procesarlo. Una técnica marginal, primaria, que intentaba entrar en contacto, con la fragilidad de las sombras amazónicas.

El primer fotograma fue de una palmera de 30 metros de largo, una imagen simbolica del vínculo entre lo divino y lo humano de la cultura local, los Esejas. Luego de seleccionar la palmera, la levantamos en un pequeño vado del río sobre una serie de bambús y dejamos echados los 30 metros de palmera flotando a unos 15 cm sobre la arena. Regresamos de noche para exponer con un pequeño flash la palmera, 25 destellos deberían de ser suficientes.

Esa noche regresamos como estaba previsto. Sin embargo, cuando estaba a punto de activar el primer destello del flash para exponer la palmera, súbitamente, arrancó una tormenta tropical. Cuatro destellos majestuosos iluminaron en pocos segundos no solo la palmera sino toda la selva.

Hace más o menos 185 años Henry Fox Talbot, científico y fotógrafo inglés, dijo que la naturaleza se dibujaba a sí misma en el fotograma. 185 años después, esa frase se materializaba en esta experiencia: una tormenta acababa de exponer con cuatro destellos una palmera de 30 metros sobre un soporte fotosensible

En ese momento, tomé conciencia de un aspecto que se ha convertido en esencial en mi trabajo posterior y en factor clave de la propuesta Huellas cósmicas: en el proceso de gestación del fotograma, mi equipo y yo, solo habíamos sido mediadores para que Ella, la Naturaleza, se hiciera un retrato.

Habíamos perdido totalmente el con- trol del proceso y habíamos comparti- do el proceso por el que se generaba la imagen, ninguno de los dos —ni el grupo de humanos ni la naturaleza misma— hubiera podido hacerlo sin la colaboración del otro. Fue una experiencia conjunta.

Habíamos también implementado una forma de ver distinta, no veíamos con la vista como la tradición óptica, veíamos por CONTACTO, el ojo había perdido protagonismo y la piel, el tacto, representado por el soporte fotosensible se había converti- do en el medio para ver.

El último día antes de regresar a Lima con las piezas, Cesar Marichi, cabeza de la etnia Eseja, me dijo “Roberto, es interesante ver cómo has ido desaprendiendo muchas cosas de tu cultura, ahora te relacionas de una forma mucho más horizontal y respetuosa con la Naturaleza, es así que Ella después de más de dos años, ha decido aparecer en tus imágenes para que ustedes se las enseñen a los otros”.

Esta aventura comenzó hace poco mas de dos anos cuando Alicia Kuroiwa, en nombre de WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society), y Armando Williams como curador, invitaron a un grupo de pintores, cocineros, escultores, músicos y fotógrafos a pasar una semana en la reserva natural intangible de Bahuaja Sonene, con la intención de motivarnos a desarrollar una propuesta para darle mayor visibilidad a la reserva.

A partir de esa experiencia y de múltiples viajes a la reserva, fui involucrándome con el territorio, con el paisaje, con su tiempo. Poco a poco fui configurando una serie de ideas y sensaciones, como el estado de conciencia distinto, los estímulos disimiles a todos nuestros sentidos, la particular relación con el tiempo, la belleza abrumadora de la naturaleza pero también a su misterio y agresividad mortal. Por su inmensidad inasible, por la falta de distancias, por su presencia extremadamente confusa para un citadino acostumbrado a relacionarse con una naturaleza domesticada culturalmente.

En este curioso proceso fui desandando, sin clara conciencia, la historia de la técnica fotográfica. Comencé buscando representaciones visuales que pudieran contener mis experiencias con distintos equipos, cámaras digitales, foto y video, cámaras de placas 10 x 12 cm y 20 x 25 cm, cámaras panorámicas, en color y blanco y negro. Sin embargo, no conseguía generar imágenes que se acercaran a lo que quería volcar como sensaciones y conceptos. Uno de los factores que me incomodaba era algo que todos estos formatos tenían en común: la representación de perspectiva óptica. Esta forma de representación no lograba traducir el territorio, el paisaje selvático adecuadamente. Quizá porque en la selva virgen casi no hay distancia para construir una imagen tradicional, es una densa marea verde que lo cubre todo.

Así decidí experimentar con lo mas primario de la experiencia fotográfica, hacer fotografía sin cámara y realizar grandes fotogramas, desprendiéndome de cualquier aparato mediatizador. Era simplemente acercarme a la selva por contacto directo y abrazarla de alguna forma con el papel fotosensible y buscar su huella por contacto directo. Lo mas primario de lo fotográfico en contacto con un espacio igual de primario en términos naturales. Solo así conseguí imágenes que contuvieran, cargaran, condensaran muchas de las capas de sentido que mis experiencias querían volcar.

Un fotograma es la imagen obtenida sin la cámara fotográfica, por medio de un proceso que consiste en superponer el objeto a registrar sobre el material fotosensible y exponerlo a la luz directa, en este caso papel fotográfico fotosensible con un flash de mano, de modo que el fotograma es la huella, la sombra de la propia selva impresa de modo químico sobre el rollo de papel fotográfico.

Diseñamos y construimos una procesadora de papel desarmable para poder revelar las bobinas de 30 metros de largo y la enviamos por tierra a Puerto Maldonado para que luego fuera Ilevada en bote hasta el Tambopata Reserch Center TRC, que nos acogió cálidamente y nos permitió armar el cuarto oscuro o laboratorio para poder revelar las bobinas.

En el clima sallamos a buscar una zona de interés, con un follaje que nos impresionara. A veces caminando por trochas y a veces navegando por el rio. Una vez encontrado el lugar, clavábamos estacas muy grandes de bambu para marcar el camino de 30 metros a donde regresaríamos en la noche a colgar la bobina de papel, que finalmente expondríamos disparando un pequeño flash y que luego revelaríamos a la mañana siguiente.

Quiero agradecer a todas las personas, instituciones y empresas que apoyaron este proyecto, en especial a Pedro Gamboa, Alicia Kuroiwa, Mario Napravnik, Loyola Escamilo, Alejandro Castellote, Coco Moore, Sebastian Abugattas, Alejandra Watanabe, Alejandra Anchante, Armando Williams, Nilton Lazo, Carlos Navarro, Sebastian Gonzales y a todo el personal del Tambopata Reserch Center.

La inmensidad, podría decirse, es una categoría filosófica del ensueño. Sin duda, el ensueño se nutre de diversos espectáculos, pero por una especie de inclinación innata, contempla la grandeza. Y la contemplación de la grandeza determina una actitud tan especial, un estado de alma tan particular que el ensueño pone al soñador fuera del mundo próximo, ante un mundo que lleva el signo de un infinito.

Gaston Bachelard

Roberto Huarcaya inició hace poco mas de dos años un proyecto que le llevó junto a otros artistas -invitados por la organización ecologista WCS-, a Bahuaha Sonene, una Reserva Natural Intangible ubicada en la selva amazónica del sureste peruano. A lo largo del primer año, realizó varios viajes en los que constató la imposibilidad de «representar» el vasto entramado de emociones que provee la experiencia de la selva. Una paralización semejante ante la inabarcable inmensidad del paisaje debió sentir Frank Hurley, el fotógrafo de la expedición a la Antártida que lideró sir Ernest Shackleton en 1914, cuando emplazó su cámara frente al inconmensurable desierto de hielo. Dos paisajes –el de la Amazonía y el de la Antártida-, que son anverso y reverso de la majestuosidad de la naturaleza son capaces de generar una incertidumbre semejante.

La decisión que adoptó Huarcaya fue prescindir de las sofisticadas cámaras que había probado en los viajes iniciales. Optó por retroceder a los usos de hace 175 años y recuperar una de los procedimientos inaugurales de la fotografía: el fotograma. Una técnica que, sin mediar lentes ni cámaras, permitía obtener reproducciones exactas de los objetos. Su inventor «oficial»[1], William Henry Fox Talbot, al describir sus primeros experimentos con la técnica del fotograma, escribió con asombro: «La naturaleza se dibuja a sí misma». La solución de Huarcaya a la aporía de la representación que le paralizaba fue admitir la superioridad del escenario: dejar de ser autor –autoridad monolítica- y convertirse en mediador, pues no se pueden desplegar parámetros y metodologías de cartógrafo o biólogo para representar experiencias no visibles. Debía ser la selva quien escribiera con luz su propio relato, sin autorías ajenas. Sólo así se podrían activar las neuronas empáticas de la fotografía y emular a la naturaleza cuando ésta deja pasar el tiempo con lentitud para que los ciclos de la vida se completen. Sólo así podía aspirar a incluir simultáneamente las dualidades de la naturaleza: -vida y muerte, orden y caos, realidad y ficción- que coexisten en ese territorio primitivo, desbordante, misterioso, mutante y agresivo que es la selva amazónica.

Desde la empatía se accede al conocimiento; pero según dicen los investigadores, las neuronas espejo son activas durante la infancia y es muy difícil recurrir a ellas en el periodo adulto. Tal vez 175 años sean demasiados años y ahora, en el siglo XXI, dedicar mucho tiempo a aprender ya no es un activo en nuestra sociedad. Según Zygmunt Bauman, lo que se busca ahora, en la época de la modernidad líquida, son resultados y beneficios inmediatos, es decir, liquidez, en el estricto sentido financiero. Son muy pocos los que aun le piden a la fotografía que imite a la naturaleza y se demore horas o días para generar una imagen en la oscuridad del laboratorio. Huarcaya es uno de ellos: por eso volvió sobre los pasos perdidos del pasado y consiguió lo que no fue capaz de obtener en casi dos años de visitas a la selva.

La expedición que emprendió Huarcaya probablemente tenía como destino su propia búsqueda interior; y esa relación entre experiencia e introspección le dio acceso a soluciones distintas y eficaces. En el proceso que desarrollamos para obtener respuestas, el tiempo es un elemento galvanizador y proteico. Una hermosa metáfora de ese proceso es la del papel fotográfico que lentamente va haciendo visible su imagen latente –su respuesta- en el interior de una cubeta de revelador. Los ejemplos, las metáforas y las alegorías nos proporcionan «imágenes» que nos facilitan la comprensión del mundo, tanto en sus dimensiones minúsculas o anecdóticas como en las metafísicas.

Desde su aparición en la escena de las artes visuales, el fotógrafo Roberto Huarcaya (Lima, 1959), destacó por la ambición de sus proyectos, en los que a menudo el medio fotográfico se ha visto unido a otros medios de creación en combinaciones de gran solvencia que han despertado respuestas intensas de distintos públicos. Sus propuestas con frecuencia han girado potentemente en torno a la construcción de la identidad individual y colectiva de cara a situaciones que van desde lo banal-cotidiano, pasando por lo erótico como punto de inflexión de la libertad, hasta alcanzar lo político, es decir, aquello que por ser pertinente al desenvolvimiento de responsabilidades, derechos y obligaciones de los individuos en la vida en sociedad requiere atención, consideración y discusión en aras de esclarecer el ideal del bien común.

En tiempos recientes los proyectos de Huarcaya han enrumbado hacia cuestionamientos de lo fotográfico pero sin violentar el soporte mismo de la imagen, sino más bien atrayendo la atención del público hacia la configuración de la misma. Llama poderosamente la atención cómo el artista logra que se entrecrucen el rol de testigo (la mirada comprometida) con el de observador antropológico (la mirada atenta al desarrollo y texturas de una situación humana salvaguardando su integridad). Estas propuestas recientes del artista se han valido, por ejemplo, de las cámaras clásicamente indicadas para un trabajo que es claro y tajante en la presentación, pero que en los entresijos se ralentiza y avanza hacia su término sin anuncio de conclusiones.

En dirección a la sociedad peruana, la mirada de Huarcaya en obras recientes como “Playa Privada/Playa Pública” o “Pamplona/Casuarinas” es tan franca que uno puede preguntarse cómo es que elude el panfleto. La respuesta está en la distancia que guarda con el asunto a fotografiar y, ciertamente, el sujeto Huarcaya fotógrafo-ciudadano reconoce en sí mismo el potencial de una mirada posicionada a una distancia evidentemente no cuantificable pero verificable, al interior de una sociedad marcada por la discriminación en varios órdenes de cosas. Un poco como en el análisis que Aldous Huxley hacía de El Greco y sus personajes, Huarcaya parece invisibilizarse en el entorno sin ser del todo deglutido por una opacidad que podría borrar su rastro fotográfico en respuesta a una vivencia crítica. Lo que hace para asumir la ubicación cuestionadora, es tomar un lugar nuclear en el entramado, dentro de aquel organismo social que regula y, por sobre todo, excluye brutalmente.

La obra fotográfica más reciente del artista pareciera tomar un rumbo distinto, pero solo aparentemente, como quedará evidenciado. Se trata de una instalación de dimensiones sin precedentes en su cuerpo de trabajo de 25 años. Presentada en la Casa Rímac del Centro histórico de Lima, en paralelo a la exposición de una selección de la Colección de Jan Mulder, también alojada temporalmente en el mismo local con motivo de LimaPhoto 2014, su instalación Amazogramas – 90 metros de Bahuaja Sonene es el señalamiento más concreto que ha hecho hasta el día de hoy.

A Huarcaya siempre le ha interesado lo real como espacio de creación y muy frecuentemente se ha lanzado a perseguir la definición de dispositivos visuales que transformaran su lectura y permitieran experimentar abierta y críticamente con la generación de signos y símbolos. La narrativa poética en secuencias fotográficas fue una manera de explorar este terreno. También aquellas reconstrucciones fotográficas de obras elegidas de la historia de la pintura occidental.

Para la realización de los Amazogramas, ha dirigido su atención a la fotografía sin cámara y está produciendo ‘fotogramas’. El ‘fotograma’ es una imagen obtenida mediante un proceso que prescinde del aparato fotográfico y su óptica, y en el cual el papel con la emulsión sensible a la luz actúa como testigo de todo lo que entra en contacto con él, capturando su huella en directa relación a su presencia y tamaño físicos por medio de un manejo adecuado de la iluminación. La vanguardia histórica en el arte europeo de inicios del siglo XX se valió del fotograma como una salida radical de lo que se percibía como una crisis completa de la representación. Roberto Huarcaya se vale de él para hacer un señalamiento de una crisis en fase aguda en un territorio que se halla en situación absolutamente crítica dentro de lo que insistimos en llamar ‘realidad nacional’. Una vez más, Huarcaya elige tomar distancia (pese, paradójicamente, al contacto entre las partes que exige el fotograma).

Lo que ha hecho es realizar tres fotogramas para los que ha utilizado el íntegro de tres bobinas de papel fotográfico. En acciones nocturnas con proporciones de producción de cine independiente (no puede uno dejar de pensar en la ambición comparable de los vanguardistas peruanos Carlos y Miguel Vargas y sus Nocturnos fotográficos, hace casi 100 años), desplegó el papel, introduciéndolo entre los árboles en secciones del bosque tropical amazónico en la reserva nacional de Bahuaja Sonene, e iluminándolo con flash de mano, al que se sumó la luz de luna, lenta y pacientemente generó la huella visual directa, testimonio literal de especies vegetales de la Amazonía en la superficie del soporte.

Más que la simple recuperación directa de la huella de 90 metros lineales del bosque tropical amazónico en los ejes horizontal y vertical (uno de los fotogramas es de un árbol entero, iluminado por relámpagos en una tormenta), los tres Amazogramas son detonantes de percepciones y reflexiones súbitas. Presentimos lo que emerge de lo visual volcado a estas dimensiones monumentales, porque en nosotros se suscitan necesidades urgentes de elaborar otros discursos ante el desenvolvimiento de esta fantasmagoría, que está fuera de dudas –por la singular naturaleza del fotograma-, pero que aun así aparece como intangible. No solo por el impacto espectral que puedan tener estos jirones de ‘selva’ sin color, sino porque, con una mezcla de intuición y resonancia, Huarcaya en estas obras nos permite re-anudar la sensibilidad, que es como un palimpsesto de nuestra historia personal, a una dinámica sensorial agitada, en la cámara de la consciencia. Exponerlos es un acto político.

Editorial ICPNA

200 páginas

2024

Cátalogo de La Bienal de Venecia 2024

Editorial Patronato Cultural del Perú

2024

Editorial RM

160 páginas

2021

Join our mailing list for

updates about our artists.

exhibitions, events and more.